The Biden administration announced that it would set a refugee cap of 125,000 for the fiscal year 2023 after officially resettling less than 20,000 refugees in 2022 despite having the same aspirationally high cap.

According to the announcement “Memorandum on Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2023”, the Biden administration authorized a refugee cap of 125,000, broken down by the following regional caps:

Africa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40,000

East Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15,000

Europe and Central Asia . . . . . . 15,000

Latin America/Caribbean . . . . . . 15,000

Near East/South Asia . . . . . . . . 35,000

Unallocated Reserve . . . . . . . . . 5,000

Additionally, President Biden authorized the following people to be considered refugees for the purpose of admission if they otherwise meet the criteria:

Persons in Cuba;

Persons in Eurasia and the Baltics;

Persons in Iraq;

Persons in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras; and

In certain circumstances, persons identified by a United States Embassy in any location.

A few notes about the refugee cap before we discuss its feasibility. First, although refugee and asylum criteria are set by law, the president is authorized to set or adjust the refugee cap (see 8 USC § 1157). Second, the refugee cap is a cap, an upper limit, not a minimum. As we will see, it’s not unusual for resettlement numbers to fall short of this aspirational limit.

Third, resettlement itself is a complex multi-national, multi-agency process that involves public-private partnerships and lots of paperwork. Experts who work in refugee resettlement have pointed out that Trump-era policies and practices destroyed much of the refugee infrastructure. Krish Vignarajah, President of the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, told the AP that she had to close a third of their resettlement agency’s offices and lay off 120 employees during the Trump administration. It’s not easy to gear up again for larger numbers.

Despite these caveats, the basic numbers surrounding refugee resettlement paint a stark picture of the administration’s ability to reach (or even come close to) this target.

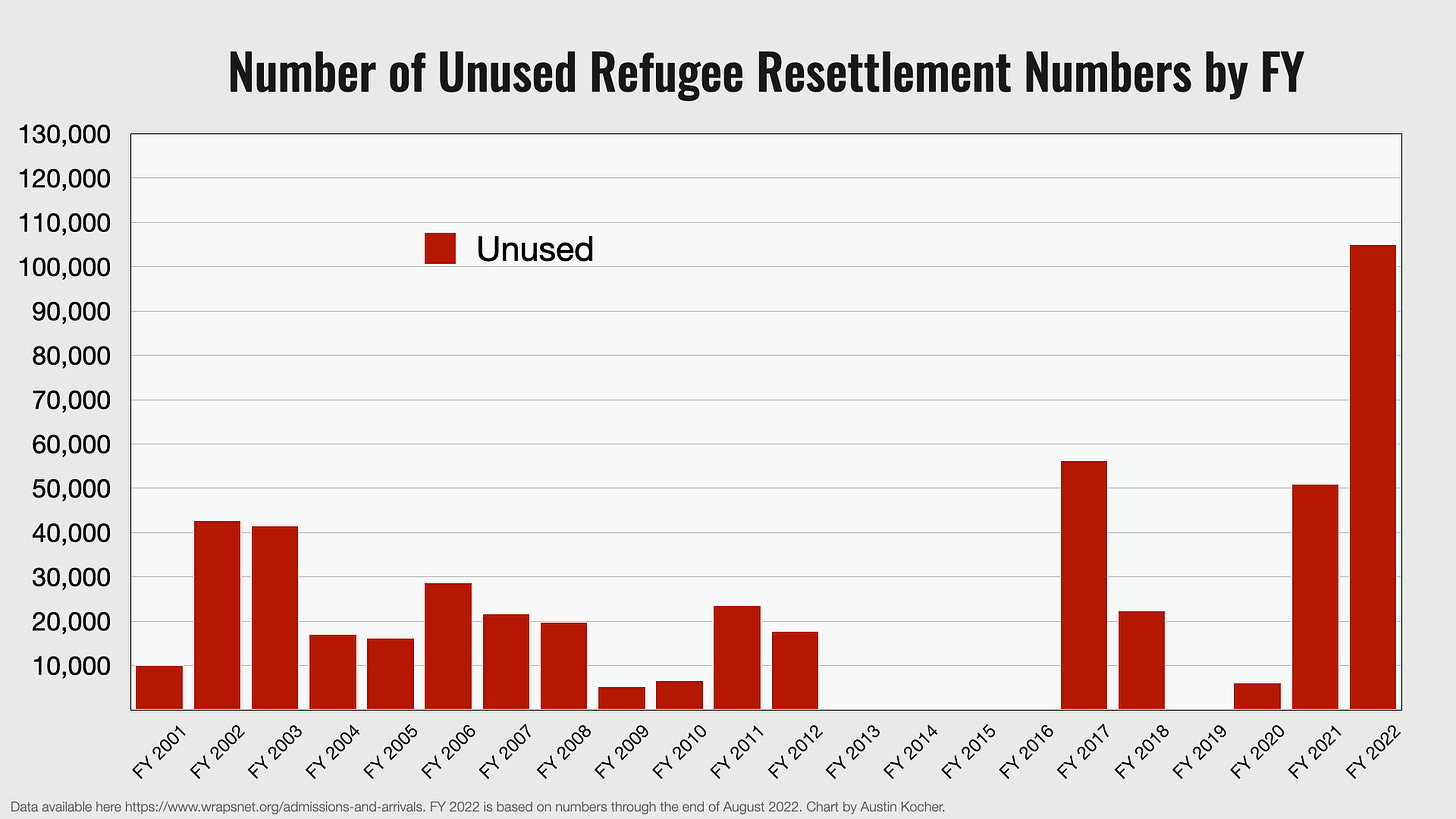

According to the Refugee Processing Center, by the end of August 2022, less than 20,000 refugees had actually been resettled, despite the Biden administration setting a cap of 125,000—a deficit of 105,000.

There is more than one way to think about these numbers.

Compared to recent years, both the number and percent of unused refugee numbers are enormous. Just 16% of all possible refugee resettlement spots were actually filled in FY 2022. Using the second figure below, we can see that the total unused refugee numbers in FY 2022 are nearly twice what they were in FY 2017 and FY 2021, and far above any other years outside of those three.

On the other hand, the Trump administration’s effects on the refugee numbers is clear in the first graph: the cap and the actual numbers plummeted to historic lows between FY 2017 and FY 2020. In 2020, for instance, the cap was set at just 18,000, and even then, less than 12,000 refugees were resettled.

Moreover, it’s not unusual, particularly under Republican presidents it seems, for the actual resettlement numbers to fall considerably short of the cap. So simply falling short is not, in itself, all that unusual. (Keep reading past the graphs.)

It’s also not as if the Biden administration has avoided responding to refugees altogether. The administration has paroled many asylum-seekers arriving at the US-Mexico border into the country to pursue their claims; they have helped to relocate Afghan refugees after the military withdraw (although they have fallen flat on humanitarian processing), and they have responded to Ukrainians fleeing the war in their home country (though, again, critics have rightfully pointed out that Haitians have hardly received the same treatment).

These responses, while imperfect, should be included in the analysis of the total state of play of the refugee system.

Where I think the Biden administration will continue to face criticism surrounding these numbers is that the refugee cap does paint an aspirational picture of where the administration would like to go, and in doing so, sets expectations for how the public will interpret the effectiveness of the resettlement system.

Set the cap too low (even if the numbers are realistic rather than aspirational) and the administration faces blowback from critics. Set the number too high and fail to achieve it (or anywhere close to it) and the administration risks appearing ineffective—even if the actual numbers of resettled refugees do inch upward as they did between 2021 and 2022.

How to make sense of all this? Here’s what I would consider the key takeaway, though feel free to add your own comments, criticisms, or questions in the comments below.

I think the nature of the US immigration system today—partly as a result of the Trump administration and partly as a result of, let’s call it, the geopolitical-slash-legal history of how the US has treated Latin American refugees—means that we simply can’t rely on the refugee system or refugee numbers to give us a good gauge of the country’s overall response to refugees. The slippage between the official refugee resettlement system and the various other pathways to refugee status (including asylum) is considerable.

I can hear some people say, “this has always been the case.” That’s true enough, but I would still argue that it has been exacerbated in the past five years. I can also hear other people say, “but we still need to invest in the orderly resettlement of international refugees!” I would also wholeheartedly agree.

I would just add (though I would need more time to explain the full argument here) that the international refugee resettlement system is, and has been, profoundly inadequate when it comes to actually resettling refugees (due far more to member countries’ refusal to take people than to refugees willingness to be resettled). This means that to truly fix the US’s resettlement system would, unavoidably, involve addressing the international system, as well—something that the US has never been particularly eager to do.

This doesn’t mean I won’t be watching to see if Biden can deliver anywhere close to the refugee resettlement cap, it just means that I’m not sure that resettlement numbers in isolation are a good enough indicator of anything worth getting excited or upset about.

Support public scholarship.

Thank you for reading. If you would like to support public scholarship and receive this newsletter in your inbox, click below to subscribe for free. And if you find this information useful, consider sharing it online or with friends and colleagues.

Cogent, insightful analysis as usual. I learned a lot in the five minutes it took me to read this. Good work.