DACA Turns 10 Years Old Today

Immigrants who came to the US as children are still largely protected from deportation, but Congress has failed to create a pathway to citizenship.

I remember the day DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) was announced in June 2012. I was in Georgia, still as a graduate student, working on a research project to examine local immigration enforcement.

Just the week before DACA was announced, I had been conducting courtroom observations at the Atlanta immigration court, which were, at the time, some of my very first courtroom observations. As some of you will know, the Atlanta immigration court is, shall we say, trial by fire for anyone observing removal proceedings.

President Obama announced DACA in the Rose Garden on June 15, 2012 (a Monday), following Congress’ failure to pass the DREAM Act. The memo issued by Janet Napolitano is available here, and notice Mayorkas (now DHS secretary, then USCIS director) listed on the memo.

Obama put the blame on Republicans, saying: “Both parties wrote this legislation. Democrats passed the DREAM Act in the House, but Republicans walked away from it. It got 55 votes in the Senate, but Republicans blocked it. The bill hasn’t really changed. The need hasn’t changed. It’s still the right thing to do. The only thing that has changed, apparently, was the politics.”

The New York Times reported that the policy provided the following benefits:

“The policy, while not granting any permanent legal status, clears the way for young illegal immigrants [sic] to come out of the shadows, work legally and obtain driver’s licenses and many other documents they have lacked.”

But what this meant in practice was still unclear.

The day after DACA was announced, I went back to the immigration court curious to see how the judges would handle the cases of young people who might qualify and to talk to attorneys about if and how this new policy would shape their legal strategies when representing immigrants in removal proceedings.

I remember on that Tuesday asking an immigration attorney what she thought the implications of the new policy might be, and she said something to the effect of, “Attorneys are asking for extensions in cases that appear on their face to qualify, but we won’t know for sure until we learn more about the details of the program”—a response that I would become all too familiar with in the years to come.

Ultimately, we did learn a lot about how DACA worked. Over the course of the summer, I spoke with young people applying for DACA who were concerned about getting background checks at police stations after spending their lives avoid police because of the risks that they and their families faced.

When he announced the program, President Obama went on to emphasize the limitations of DACA: “This is not a path to citizenship. It's not a permanent fix.”

He wasn’t wrong there. In the decade since DACA was implemented, outside a very narrow set of exceptional circumstances, DACA recipients have had no path to citizenship despite well-documented research that they have otherwise contributed tremendously to society.

In the past decade, 800,000 people have benefited from DACA—although as I showed yesterday, the current number of active DACA recipients is around 611,000. The Migration Policy Institute shows the total number of active recipients over time.

One of the most important stories behind DACA, a story that immigrant rights organizers have remained frustrated hasn’t received more attention, was that without grassroots organizing DACA likely never would have happened.

Adrian Carrasquillo for BuzzFeed wrote a great article back in 2014 that described the story that most people don’t know about the organizing movement that pressured Obama to take action. It opens with an excellent lede:

“President Obama’s executive actions to give legal status to millions of undocumented immigrants have been framed as a president choosing to be confrontational and daring. But the real story is different: Obama was forced to do this.”

Luis Cortes Romero, a DACA recipient himself, later wrote that “activism leads, and the law follows,” reflecting the ongoing relevance of social movements to shaping what becomes politically feasible, not the other way around.

I have known many DACA recipients over the years. Some of them were empowered to speak out even more for family members, often for their own parents, who were not afforded the same legal protection. Others were quiet about their DACA status, preferring instead to use the opportunity to blend in and avoid scrutiny.

Some who had the resources and interest pursued college, went into the workforce, and became engineers, nurses, and teachers. A survey from the Center for American Progress in 2021 showed that DACA recipients were able to move to better-paying jobs that fit their long-term career goals, they paid more in taxes, they were more likely to be in school and employed—all outcomes that benefit society as a whole, not just those who received DACA.

Others who justifiably feared the consequences of renewing their DACA status during the Trump administration or who became ineligible due to the kind of minor criminal charges that disproportionately affect people of color fell out of status and returned to a life of legal precarity.

DACA is one of those many policies that has a peculiar history of public perception. It was incredibly controversial at first, but relatively quickly became accepted as not only normal but as a public good. The Trump administration’s attempt to roll back DACA does not shake my perception of this, since, as the polling data clearly and consistently showed, many of Trump’s immigration policies were extremely minority policies that did not reflect most constituents including Republicans.

Indeed, it is worth remembering that when DACA was announced, even many otherwise pro-immigrant attorneys either questioned it’s legality or felt uncomfortable with the precedent they feared that DACA might set and questioned its legitimacy, if only privately. Shoba Wadhia wrote a fantastic article back in 2013 titled “In Defense of DACA, Deferred Action, and the DREAM Act” which addressed many of the legal questions surrounding the program and arguing that questions about the program were “policy questions, not constitutional ones.”

One attorney I knew expressed concerns about DACA to me back in 2012, worried that such a policy would prompt a series of politicized executive volleys that bounce back and forth from administration to administration. By 2019, whatever this attorney’s original concerns were, he had changed and was now strongly supportive of DACA after seeing how the program benefited so many people.

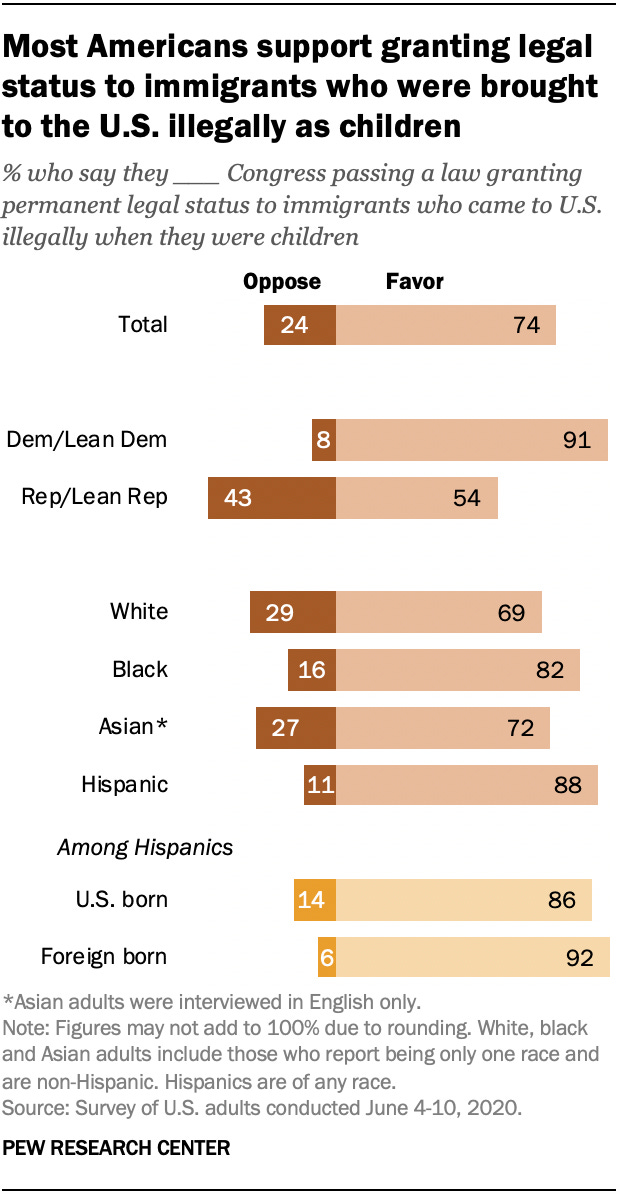

This was true nationwide. A Pew Center poll in 2020 showed that the majority of people—fully 74% of all people polled including 54% of Republicans—supported a pathway to legal status.

Despite this amount of support, DACA has faced many legal challenges. In 2017, Jeff Sessions announced that the administration would be rescinding the DACA program. Sessions described DACA as “essentially providing a legal status” to “mostly-adult illegal aliens” and a policy that circumvented the legislative process.

Despite the Trump’s well-documented attempts to end the program, a series of lawsuits that alleged that the rescission was unlawful prevailed, initially protecting existing DACA recipients then expanding to allow new applicants—although due to the age requirements, fewer and fewer people qualified.

As UndocuCarolina pointed out last year, despite the many advantanges of DACA, there were (and increasingly are) many limitations to the DACA program. For one, DACA recipients never made up a very large proportion of undocumented immigrants in the United States.

DACA in many ways also forced young immigrants to, as one undocumented activist told me, “throw our parents under the bus” because of the ways in which the program perpetuated a narrative that children should not pay for the crimes of their parents (thereby implicitely deligitimizing their parents as criminals).

On a more personal note, it also meant that a whole generation of DACA recipients coming of age in the United States bore the economic and relational burden of taking on responsibilities that only they were eligible to take on. From opening a bank account to driving their siblings to school and redistributing their better wages with the rest of the family, DACA recipients also took on unique roles in their families and in their communities that was (is) not always easy.

DACA turns 10 years old today. It’s a policy that has benefitted me personally not because I received DACA, but because I have had the privilege to work with many colleagues and collaborators over the years that I would not have were it not for the program. At the same time, it’s a bitter anniversary. DACA was intended to provide temporary protection so that Congress could get its act together. Instead, Congress has only become more disfunctional and incapable of passing immigration reforms that the vast majority of Americans support.

To learn more about DACA, I would of course recommend that you first listen to the voices of Dreamers, DACA recipients, and people who were left out (or kicked out) of the program. Some profiles and essays are available online, such as that of journalist Prioska Galicia or United We Dream organizer Juliana Macedo.

People are also sharing their experience with DACA online today.

I would also highly recommend the late great Michael Olivas’ book “Perchance to DREAM” that provides a thorough history of DACA.

THANK YOU FOR READING!

If you found this information useful, help more people see it by clicking the ☼LIKE☼ and ☼SHARE☼ button below.

Everyone deserves a happy ending to their life story. It's far past time to give the DACA kids a clear pathway to citizenship. Hang in there, Dreamers!