When Elon Musk, the world’s richest man and CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, made the announcement earlier this year that he was going to buy Twitter, I was indifferent. I didn’t (and don’t) like Elon Musk, but I could appreciate the fact that he was innovative in fields I understand very little about and could, under the right circumstances, bring some of that innovation to bear on a social media platform plagued by financial and operational problems. I had an open mind.

This open-minded view was not shared by everyone I knew. There was a substantial, but not what I would consider overwhelming, outpouring of frustration over the deal, typically expressed as a desire by people to delete their Twitter accounts. I don’t remember seeing any widely-recognized commentators pull the plug or even seriously consider it, but I did see a few (very few) people follow through with leaving the platform. I wouldn’t have characterized those decisions as overreactions; I believe everyone should do whatever makes their lives better. But my engagement on Twitter is primarily in the service of my research and of sharing TRAC’s research (even if I do pop off about other things, too) and I could see all benefit and no cost to staying on Twitter. Leaving Twitter did even not cross my mind.

As a matter of coincidence, I began listening to the Pivot Podcast with Kara Swisher and her long winded co-host Scott Galloway (I like Scott, but c’mon, man) around the same time as Musk’s announcement. Kara’s and Scott’s regular updates and assessments shaped how I thought about the deal. Scott routinely emphasized Musk’s irresponsible behavior as a man and as a business leader (check and check), and drilled in on the legal shenanigans that Musk was trying to pull to get out of the Twitter deal that he signed. Galloway said early on that Musk will buy Twitter. He was ultimately right.

By the time the Musk-Twitter deal was finalized and Musk walked into the headquarters of office carrying a kitchen sink (dumb, but true), I had developed a somewhat informed concern that this was going to be a bad thing. Musk’s behavior on Twitter (which I had never noticed before) was trollish and petty to begin with but the more I paid attention (and the more his tweets circulated), they grew increasingly unhinged and incomprehensible, to the point where it was clear that Musk’s online behavior was compromising his own business interests. In short, Musk was putting his own companies at risk over…tweets. (Note that I will no longer be linking to Twitter content directly.)

From the day Musk took over Twitter, I noticed (or felt I noticed) a shift in the discourse on the platform. Many people were concerned that Twitter’s moderation would be eliminated, that Trump would be allowed back on the platform—that kind of thing. But that’s not what I mean. What I mean is that the conversation on Twitter suddenly shifted towards talking (obsessively) about Twitter itself. This was a logical consequence of Musk’s behavior, not mere projection, since Musk began immediately firing people, getting into arguments with elected officials, and issuing vague assertions about radical change that were detached from any concrete details. But this shift in discourse also immediately undermined the best part of Twitter: the fact that most of the conversations on Twitter isn’t about Twitter, but about other, more interesting things (immigration law and policy, for me).

Don’t take my word for it, though. Musk’s takeover of Twitter has had at least three demonstrable consequences in a short period of time that raise substantive concerns about the future of the tone on Twitter.

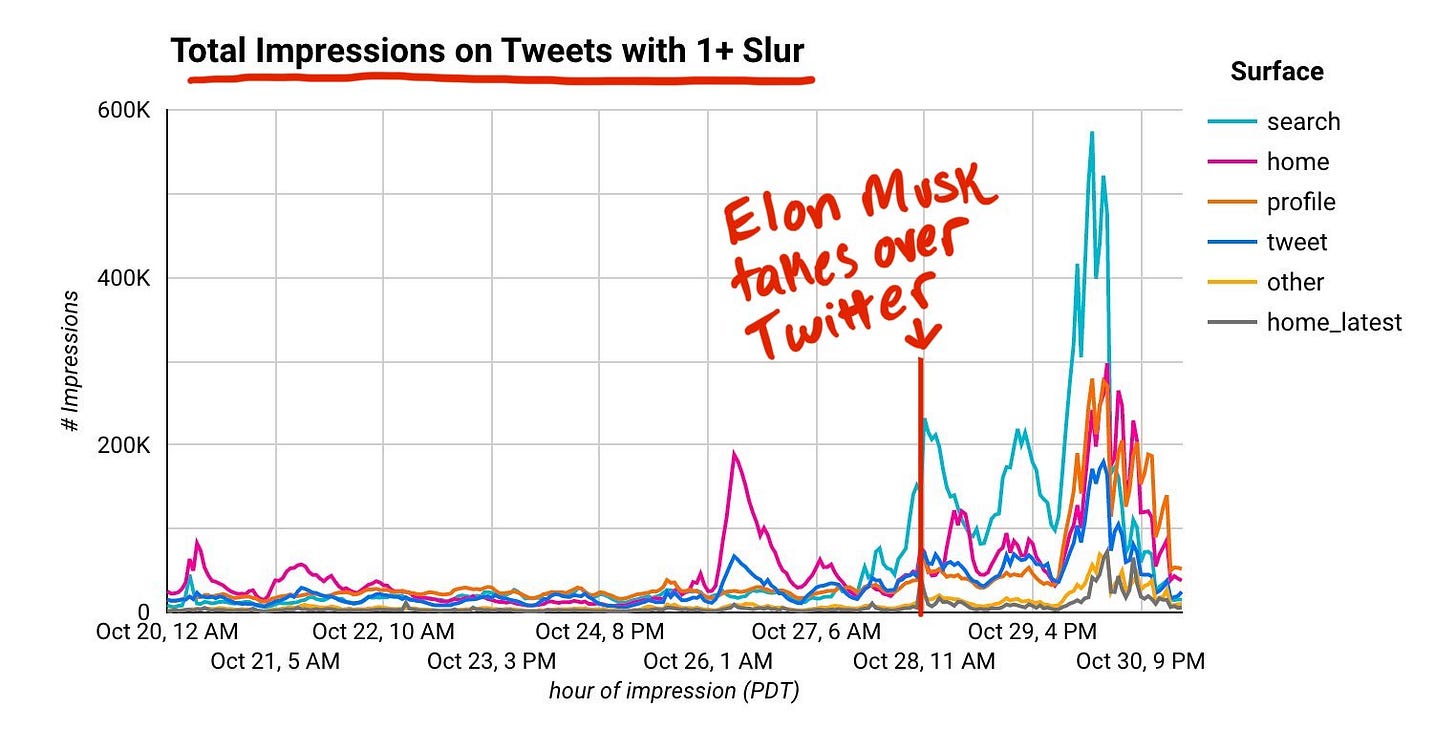

First, the platform saw a massive rise in racial slurs literally overnight, with the use of Nazi language and memes growing suddenly and instances of the N-word reportedly increasing 500%.

It appears that this was a concerted and intentional exploitation of the platform to share offensive content, at least that’s how Twitter’s Head of Safety and Integrity described the situation in a tweet. Twitter apparently sought to distance itself from the worst of the bad-faith actors, but could not bring itself to acknowledge Musk’s role in inspiring such attacks on the platform.

The company reasserted its claim that no changes had been made to content regulation, an assertion that Elon Musk himself, who rather pathetically did not comment on the rise in hate speech, repeated later this week.

Musk failed to appreciate an obvious contradiction in all this: that as a self-described “free speech absolutist”, the use of racial slurs, or any other offensive language of any kind, is beyond the scope of the debate. If people don’t like it, according to this absolutist principle, they have the freedom to look away, but regulating such speech is not the job of governments nor of corporations.

Already, then, Musk is running into an essential, wicked problem of social media platforms that he was quick to criticize from the outside but now has to navigate from the inside: content moderation. And because he clearly hasn’t developed a sophisticated framework for thinking about it and talking about it, his messages are entirely incoherent. So incoherent, in fact, that he has angered some people on the right for even mentioning content moderation and for not bringing Donald Trump back to the platform yet. This confusion is a result of his own doing.

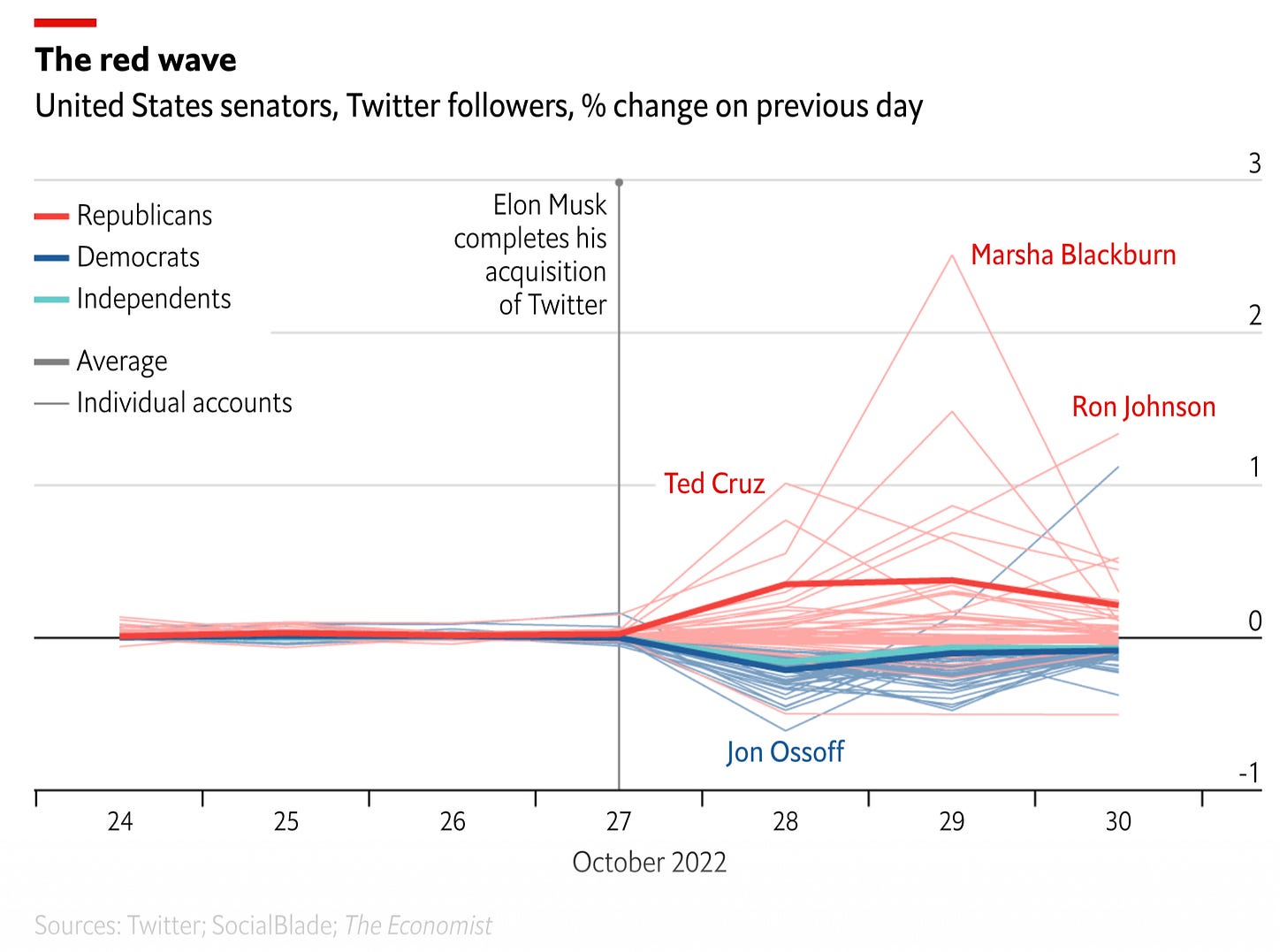

Second, and somewhat relatedly, The Economist found that Musk’s takeover of Twitter had an immediate effect on political engagement on the platform: Democratic Senators and many other Democratic politicians lost followers while Republican Senators and right-wing figures gained followers. The Economist described this as a gravitational shift to the political right on the platform.

Under normal circumstances, I wouldn’t particularly care about whether people are posting as Democrats or Republicans on a social media website. But in an election year where most of the Republican candidates have refused to publicly accept the results on the 2020 election (they all accept it in private, let’s be clear), this shift in Twitter users could mean that bad actors will have even more influence than two years ago when a pro-Trump mob attacked the Capitol building. That’s a scary thought.

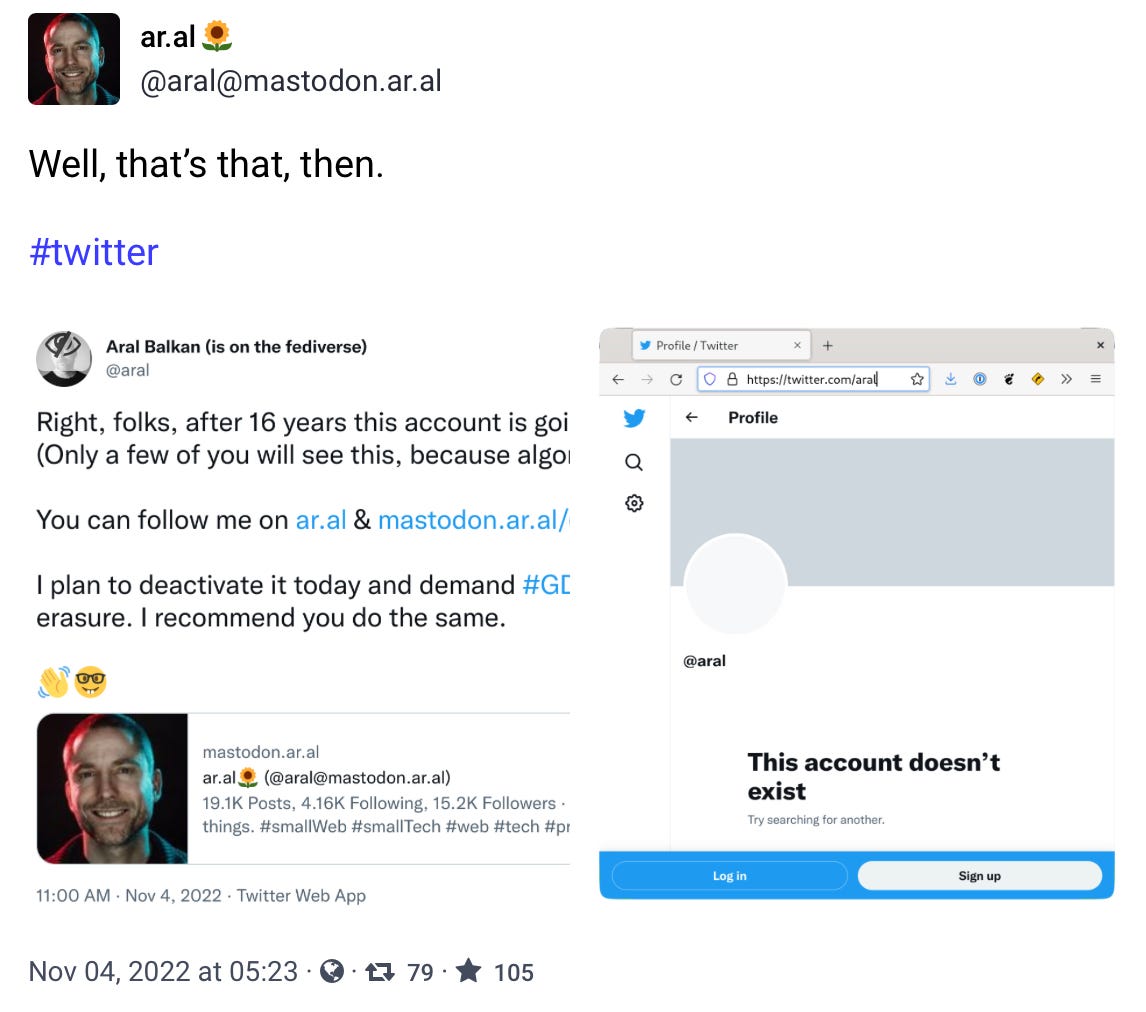

What’s driving this data? From looking at the data, it’s certainly plausible that right wing users were attracted back to the platform or began engaging with more intensity on the platform under the assumption that the gloves had come off of Twitter’s content moderation. At the same time, liberal-leaning users could have reduced engagement or made up a larger part of the nearly one million users that have removed their accounts entirely. This was the case for Aral below who posted this on Mastodon.

Third, and the most immediately concerning for Twitter is that advertisers have already begun to pause advertisements on the platform. A (growing) list compiled by Newsweek already includes Audi, General Mills, General Motors, Pfizer, and VW, though many other companies are signaling their concerns.

The obvious problem with this is that what insufficient but reliable revenue Twitter does have comes from ad revenue on the platform (I believe I read something like 95%). So that’s the money coming in. Twitter has never been particularly profitable and while I don’t know how much debt Twitter was in when Musk bought it, it seems like it is substantial. Add to that the fact that Musk himself leveraged most of the money to buy Twitter against Tesla (SpaceX, too?) but still had to borrow $13 billion dollars. So on Day 1 of the Twitter acquisition, Musk is in debt for however much Twitter’s existing debt is, plus $13 billion dollars from investors in a company that has yet to find a way to generate any income, plus the fact that he bought a 13 billion-dollar company for 44 billion dollars. Musk basically went into massive debt buying what is, at best, a charity.

What is the Richest-slash-Smartest Man in the World’s brilliant plan for getting out of this mess? For starters, he wants to charge $8/month for for account verification (basically those little blue checkmarks, or what I like to call Star-Bellied Sneetches after the excellent Dr. Seuss book). Let’s do the math on this. There are about 400,000 blue-checked users right now on Twitter. If everyone converts, and so far many (many) big names have already said they absolutely will not, this comes to $3.2 million each month.

Now let’s put this in context. Take just Musk’s $13 billion in personal debt, which one could argue he generated purely out of hubris over this deal, not as a serious business decision. At that rate of monthly income, it would take 4,062 months or 339 years to pay off just what he owes investors. That’s how much bigger 13 billion is from 3.2 million. And by the way, in 2021, Twitter did better the year before but still lost $221 million. And Musk is out there claiming that $38.4 million a year in pay-to-play verification is even remotely viable.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I don’t really care if the wealthiest and most famous users on Twitter get charged for a platform that has advanced their interests and helped them create financial value for themselves. But that’s probably not actually most verified users. Twitter’s largest verified base is probably start-up reporters who are trying to survive in an extremely challenging news ecosystem by connecting to readers and finding stories online. And there are many other issues with a payment system for verification, namely that it may exacerbate rather than fix the bot problem.

But never mind all that: my main point is just that I can’t make the math make sense in my head—especially when you take into account the fact that due to Musks own self-inflicted wounds, now advertisers and public figures are less likely than ever to actually support this new direction.

Of course, Musk blames what he calls “activists” who forcing companies to withdraw advertising, apparently unwilling to conceive of the fact that sharing conspiracy theories about Nancy Pelosi’s husband, repeatedly attacking a Congresswoman, and picking a petty fight with Stephen King (as well as the rest of the issues I mentioned above) might make advertisers and celebrities skittish.

In an entirely typical—even stereotypical—example of a man dizzy from toxic masculinity and deluded by an infantile obsession with being the center of attention, Musk cannot seem to fathom that these are the logical consequences of his own actions.

The following quote published in the New York Times by Nicole Gill, executive director of the nonprofit group Accountable Tech, is the defining quote for me right now.

“We are witnessing the real-time destruction of one of the world's most powerful communications platforms.” —Nicole Gill, Accountable Tech

Already, around a million users have deleted their Twitter accounts (though some new users have probably been attracted to the website), and many people have created accounts on other social platforms such as Mastodon. I certainly have, and you can find me here. I’m not at all saying that I’m removing my Twitter account, but I will be reducing my engagement on that site considerably over the next few weeks while I’m busy with fieldwork along the border (more news to come about that!) and while I spend what limited time I have test-driving Mastodon and focusing on this Substack newsletter.

Already an enormous number of people I know professionally and personally have made the leap to Mastodon, far more than I would have thought. It feels very much like a tipping point. Most of who I think of most readily as being a part of #AcademicTwitter are on Mastodon, which greatly smooths the transition over for me. Today I saw a more modest increase in people from #ImmigrationTwitter, while the smallest growth so far has been among working journalists and reporters, though that too is changing.

It’s not all rose-colored glasses. There are major questions about what the shift away from Twitter (if it is significant and permanent) will mean for, say, scholars of the global south who have relied on Twitter for years to get their research out, or reporters living in oppressive regimes who could use Twitter to tell powerful stories. Social media fragmentation could mean that those voices become more isolated, or that the power of, say, #BlackTwitter could be diminished. Lots of questions remain, including questions we don’t even know are questions yet.

The takeaway is: Twitter’s hegemony as the de facto public forum is in major jeopardy and although Elon Musk isn’t the only one who prepared the kindling, he is certainly drenching Twitter in gasoline and flicking lit matches at everyone around him. Twitter will probably be around for years to come, I’m not saying it will shut down soon. But unless something changes—I mean really changes—this is the start of the long end of Twitter. Maybe it’s for the best.

I've really not seen or experienced anything differently on Twitter. I don't follow Musk or any celebrities, so maybe that's why it seems "normal" enough. My posts still attract those horrible NAFO doggie cartoon faced 'bots screaming at me because I don't believe in war. (War hawks obviously don't like peace activists. Nothing new there.)