Immigrant Detention in Focus: The Unconventional Photography of Greg Constantine

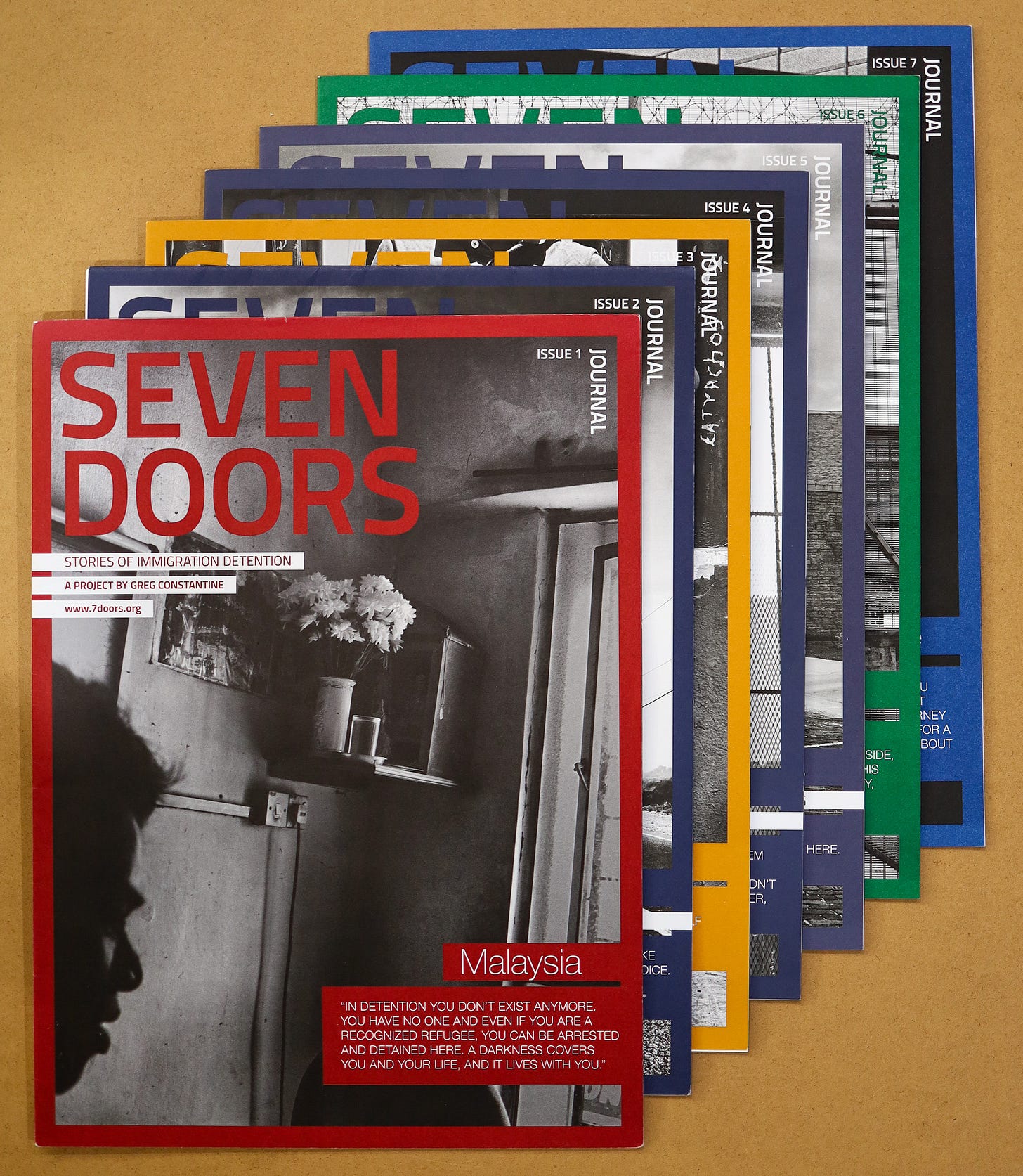

Greg Constantine's "Seven Doors" project captures the lives and stories behind immigrant detention in the United States and around the world through patiently composed photographic essays.

When the first issue of Greg Constantine’s photo-ethnographic study of immigrant detention arrived in the mail, it immediately struck me as the kind of uniquely ambitious, grittily honest, and deeply human approach to visual storytelling that has the power to help us see detention from new angles. Now, after spending the past two weeks putting the full collection of Greg’s photographs in conversation with academic, artistic, and activist approaches to thinking about detention, I am even more convinced that his work speaks to our historical moment and to the uncertain four years ahead.

Greg Constantine’s Seven Doors project, produced as a series of carefully composed chapters of photographs, interviews with migrants, and data, is the culmination of years of work that took him to Malaysia, Mexico, the U.K., and across Europe and the United States. His richly textured black-and-white photographs reveal detention architectures that blend seamlessly into the American landscape, show families navigating the convoluted bureaucracy of visiting a loved one, and capture the despair, faith, and endurance of those held within this enormous global archipelago of containment.

These photographs have been at the forefront of my mind in recent weeks as I grapple with finding new ways to write about immigration in meaningful ways—without becoming subservient to the volatility that will characterize the next four years. I believe you, too, will find tremendous meaning in Seven Doors, which is why I am devoting this post to discussing Greg’s work. If you’d prefer to have this essay read aloud, open it in the Substack app and click ‘play’—it’s that easy.

Greg was also kind enough to join me for a wide-ranging discussion that takes you behind the scenes of his approach to photographing detention centers. I think you’ll find it fascinating. Click the link below to listen to the interview. (If you are reading this in your email, you may have to visit the full article online to see the link due to a delay in publishing both posts.)

The additional work that went into this post was made possible thanks to paid subscribers who generously support the creative expansion of this newsletter and keep it running without a paywall. Learn more about how and why to support this work here, and consider subscribing below.

I was first introduced to Greg in 2018 through Brian Hoffman, an immigration attorney and fellow Ohio native, who completed law school at Ohio State University while I was in graduate school. Brian’s influence on how I understand immigration detention cannot be overstated. In 2015, Brian was hired to run the CARA Pro Bono Project at the South Texas Residential Facility in Dilley, Texas, a program that provided legal support to asylum-seeking mothers with children who had recently crossed the border. At Brian’s urging, I soon found myself in Texas with him, schlepping boxes of client files into the family detention center under the skeptical eyes of CoreCivic employees and attending Brian’s debriefing sessions at the end of each exhausting day. He ran these sessions with the cheery urgency of someone simultaneously coaching a Little League team and disarming a bomb.

My weeks at CARA not only deepened my admiration for Brian and the many volunteers who made that project possible, but also taught me much about the inner workings of the detention system. Mostly, I learned that migrant detention functions as a relentless humiliation machine designed to slowly eviscerate migrants’ humanity and create barriers to due process. That’s not to say there were no signs of endurance or glimmers of hope. We familiarized women with the asylum process, held the occasional all-too-brief birthday parties, and celebrated important wins. But what I remember most—especially from those early days—was what scholars call the “bureaucratic violence” of the system, which aggregated seemingly banal routines into an apparatus with a coherent objective: to discourage migrants from coming to the United States or compel them to give up and return home once they were here.

Even as someone who wasn’t facing deportation, spending week-long bursts of time inside a detention facility changed me. It helped me understand the gravity and seriousness of the work I was doing, even as a researcher, and ignited a curiosity and passion for understanding immigrant detention. I knew there would always be others better suited for advocacy, and, in any case, I was more interested in thinking through (and writing about) the relationship between these complex immigration systems and real people. Even then, I knew we needed to find ways to represent detention that prompted sincere moral questions without reproducing the voyeurism of standard media accounts.

So when Brian, who had since moved back to Ohio, introduced me to Greg in 2018, I was enthusiastic about the prospect of a photographic account of immigrant detention. Moreover, Greg was in Ohio, and let me tell you—that was a big deal at the time. Ohio then (and now) is often overlooked as a site for immigration research, so it meant something to me that Greg was taking the time to be both attentive and thorough. As Greg explains in our audio discussion, to understand the full network of detention centers, one cannot simply look at the enormous 2,000-bed facilities in Georgia or South Texas. One must also account for the county lockups and regional facilities, whose normalization is profoundly connected to the banality of their architecture and geography. That means not just going to the border, but also to northern Michigan, the suburbs of Tacoma, Washington, and rural jails in Ohio—all home to arterial waypoints, big and small, that make detention possible.

But doing that work takes time—a lot of time. Greg’s commitment to patient, long-term photographic research came through in those early conversations, and, more importantly, is evident in the finished work. As I mentioned at the outset, the early issues of Seven Doors struck me as honest and intimate portraits of what I had seen for myself and what I had learned from others through years of research. Seven Doors is the work of someone committed to getting it right rather than getting it fast.

Greg’s black-and-white photographs of detention center architectures place these unassuming edifices in their landscapes. From the El Paso Service Processing Center along the U.S.-Mexico border to the Heathrow Immigration Removal Center in the UK, Seven Doors shows us the overlooked spaces of confinement that function typically without spectacle, blending into the everyday routines of the places around them or, when more remote, blending into the desert landscape around them.

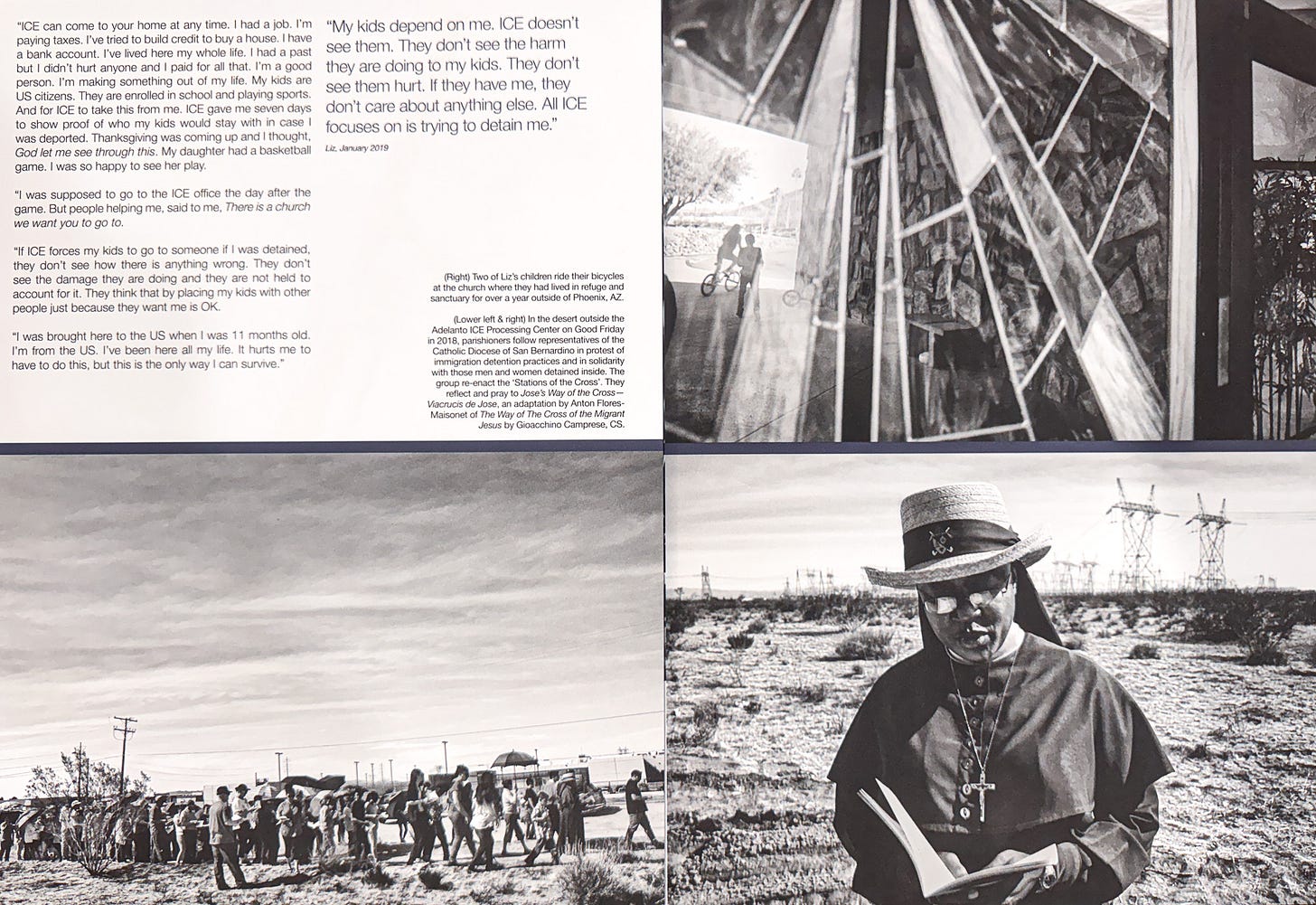

Greg does not typically show photographs of detention centers on their own, which could have implied a kind of detached, value-neutral perspective. Instead, Seven Doors places the voices of people detained in those facilities alongside the facilities, allowing juxtaposition of the dryly bureaucratic and profoundly personal to tell the story of what goes inside these opaque structures. These first-hand accounts, in turn, frequently speak not of visible walls and doors and barbed wire, but of the invisible toll that, say, being separated from one’s children takes on a parent or the toll that being detained for months without an end in sight takes on one’s sense of dignity and hope.

It’s as if Greg is trying to show us (rather than tell us) that although we think of detention as a place, as a building, as a structure, that most of the violence of detention is invisible, not visible, and that, therefore, perhaps the best way to tell a visual story about migrant detention is through people, not simply architecture.

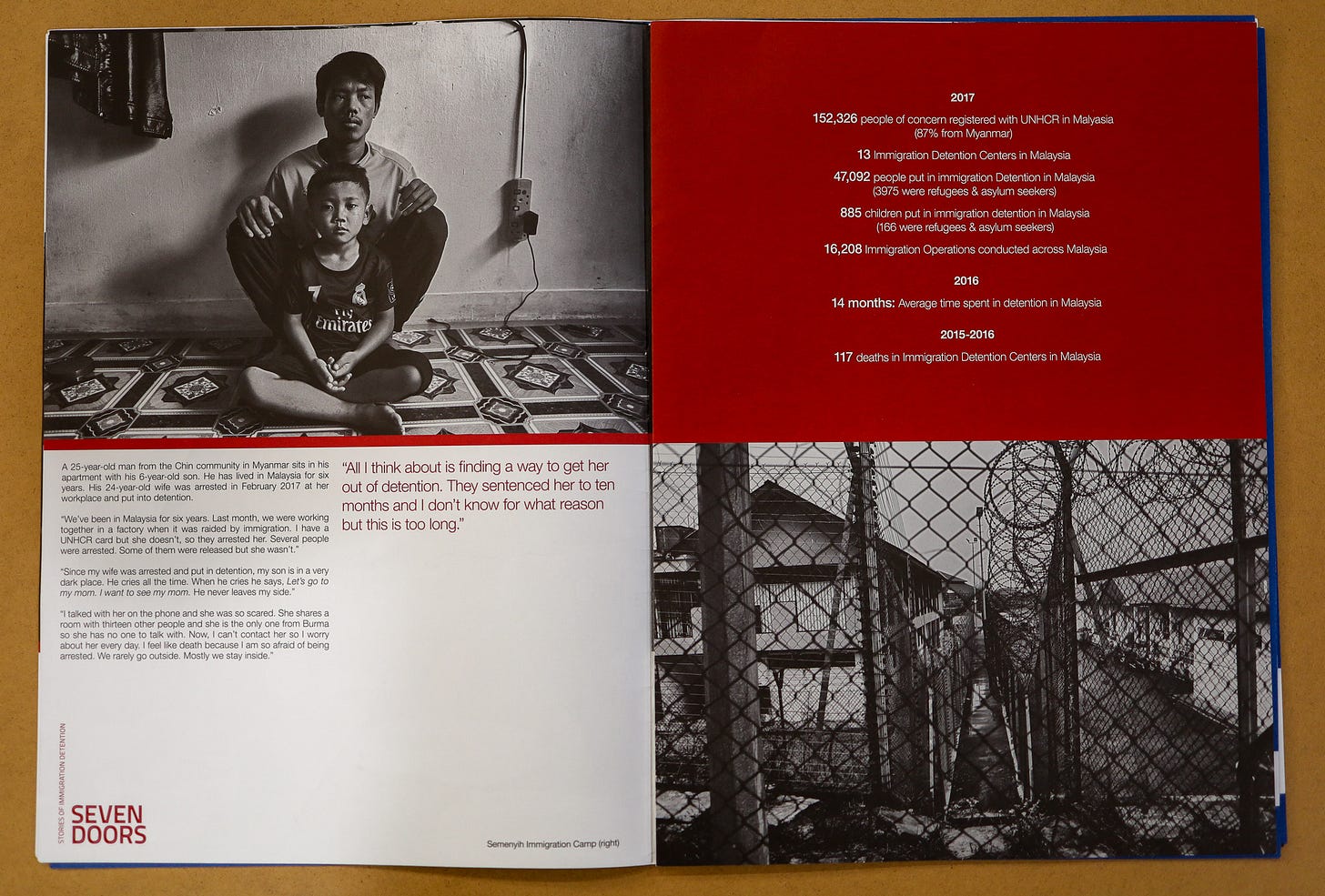

If Greg had limited himself to the US detention system, he would have already done us a tremendous service. But the United States only makes up three out of the seven issues of Seven Doors. The others include Malaysia, home to thousands of displaced Rohingya, the UK, mainland Europe, and Mexico. I can’t overemphasize the importance of putting these various geographic contexts into conversation with one another; it has the powerful effect of challenging the exceptionalism of the United States and seeing the global scale of detention.

On any given day right now, about 40,000 immigrants are held in over 100 facilities in the United States alone, but tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, more are held in facilities around the world. And increasingly transit countries like Mexico and countries in Northern Africa are expanding their detention systems in order prevent migrants from arriving at the borders of the United States, the EU, and Australia.

Some facilities in certain parts of Europe appear more like welcome centers and hotels (indeed, many of them are refurbished hotels) than American-style prisons. Many detention centers are simply bad in different ways. And many more still are brutally exploitative, carefully located beyond the protections of purportedly liberal legal systems on remote islands or in regions run entirely by gangs of human traffickers. The fact that the prison in Guantanamo Bay began as an immigrant detention center, and has never ceased to exist for this purpose, illustrates the ongoing entanglements between Cold War geopolitics, the post-9/11 War on Terror, and the ongoing economic and climatological catastrophe that (mostly) countries in the Global North, including countries in North America and Europe, have inflicted on (mostly) countries in the Global South.

Greg grasps the enormity of the problem and its interconnections in no small part because of how he entered into the project on detention. Greg’s prior project, focused on statelessness and titled Nowhere People, is a similarly sophisticated study of the lives of people abandoned not by any one nation-state but by the very concept of national belonging itself. As Greg discusses in our audio conversation, he found that many of the stateless people he spoke with shared stories of being cycled through immigrant detention centers—and he followed the thread. In fact, I like to think that the problems of statelessness and detention are two sides of the same coin, with statelessness representing a type of abandonment to the absolute legal outside of no state and detention representing a type of abandonment to the abject interior of the state: an individual prison cell.

As we approach what promises to be an era of increased immigration enforcement in the United States (as is happening around the world—just look at recent EU policies), there is no doubt that detention will gain renewed attention. The Biden administration is expanding detention contracts as I write, and the Trump administration will very likely develop even more creative ways of holding people in untold numbers of federal and local facilities across the country.

How can we talk about mass detention, which is necessary for mass deportation? What stories do we already have available to us, and how will they inspire us to write new ones? How should we think about the visible and invisible dimensions of immigrant detention, and how can we make the invisible visible through photographs without reproducing systemic violence or further stripping migrants of their humanity and dignity?

These are the questions that brought me back to Seven Doors. Greg’s work remains more relevant, not less, today. As a series of interwoven visual narratives, Seven Doors is an original and bold project that brings us into a conversation about what civil immigrant detention should look like—or whether we should have civil detention at all. I believe that putting a single issue of Seven Doors on the table with loved ones, whether you agree on immigration questions or not, is a better conversation starter than whatever is happening in the mainstream media or on social media. Moreover, Greg’s patient disposition toward his work is both rare and (thankfully) contagious. Sitting with his work will remind you of what thoughtful artistic work looks like.

I am absolutely convinced of two things these days: (1) that we need to find new ways of talking about and representing this controversial topic of immigration, and (2) that we have to detach ourselves from the news cycle and policy frenzy in order to take a longer view of the impact we want to have and what we want to contribute to the world. Let Greg’s life and his work be an inspiration to you on both accounts. It certainly is to me.

How to Get Seven Doors and Nowhere People

There is nothing quite like holding a physical issue of Seven Doors in your hands and spreading it out on a table in front of you. It’s an experience that our screen-saturated world simply cannot replace. Copies of Seven Doors can be ordered online here. While I encourage you to explore Greg’s global work, if you’d like to start with the United States, I recommend issues #2, #4, and #5. If the issues you want are currently out of stock, consider reaching out to Greg at info@7doors.org to let him know what you’re looking for.

If you are also interested in Greg’s project on statelessness, you can learn more about his book Nowhere People or order it online. As a side note, the Nowhere People website is really built out with a lot of information about statelessness, including short videos and other resources.

Learn More about Greg Constantine’s Work

I encourage you to start with my discussion with Greg. But once you’ve finished that, I highly recommend two of Greg’s many presentations online. The first is his Tedx Talk “Nowhere People: exposing a portrait of the world's stateless,” and the second is a lecture he gave about immigrant detention at Gresham College. You can also follow Greg on Instagram 📸 and Twitter/X.

For Further Reading

Interested in more perspectives on immigrant detention? Here are a few places to start.

Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant Detention by Tings Chak is an architectural study presented through simple yet powerful line drawings that document and explore the everyday spaces of detention centers.

I cannot separate the following two books in my mind: The Handbook of Tyranny by Theo Deutinger and Borderwall as Architecture: Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary by Ronald Rael. Each leaves a distinct artistic impression, but they are otherwise on equal footing as perhaps the two most elegant architectural analyses of state violence you’ll find. Although neither focuses specifically on detention, the form of their analysis resonates with Greg’s work: sustained, critical, and creative.

In Asylum: A Manifesto, Edafe Okporo provides a moving firsthand account of the long months he spent inside the detention center in Elizabeth, New Jersey, after requesting asylum upon his arrival from Nigeria.

Perhaps the most concise yet accessible book about migrant detention in the United States by a scholar in recent years is Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking Up Immigrants by César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández.

The Vera Institute offers a functional, if now outdated, interactive map of detention facilities nationwide with their relative populations. While the data stopped being updated in 2020, the general patterns of detention centers remain roughly the same today. You can explore the map online here.

If you have other recommendations of books, articles, artistic works, or other related resources, please share them in the comments below.

Support public scholarship

Thank you for reading. If you’d like to support public scholarship and receive this newsletter directly in your inbox, please subscribe. If you find this information useful, consider sharing it online or with friends and colleagues, and supporting it through a paid subscription.

Enjoyed this very much. Great read.

See also: https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691237015/the-migrants-jail