I have become convinced in recent weeks that we are not taking the Department of Homeland Security’s massive data collection and aggregation machine seriously enough.

The agency has invested heavily in recent years in expanding its own high-tech data collection and surveillance systems, bought into large public data aggregation services, joined various data interoperability schemes, and intensified its monitoring of immigrants through new ‘alternatives to detention’ technology.

Let me try to explain a small fraction of what I mean.

Just this week, Ryan Devereaux (one of my favorite writers, on Twitter here) published a mind-bending and extremely well-researched story about Kaji Dousa, a prominent pastor in New York City, who became the target of DHS through Operation Secure Line. Dousa, who went to the border to provide support to migrants and refugees, became a target of DHS.

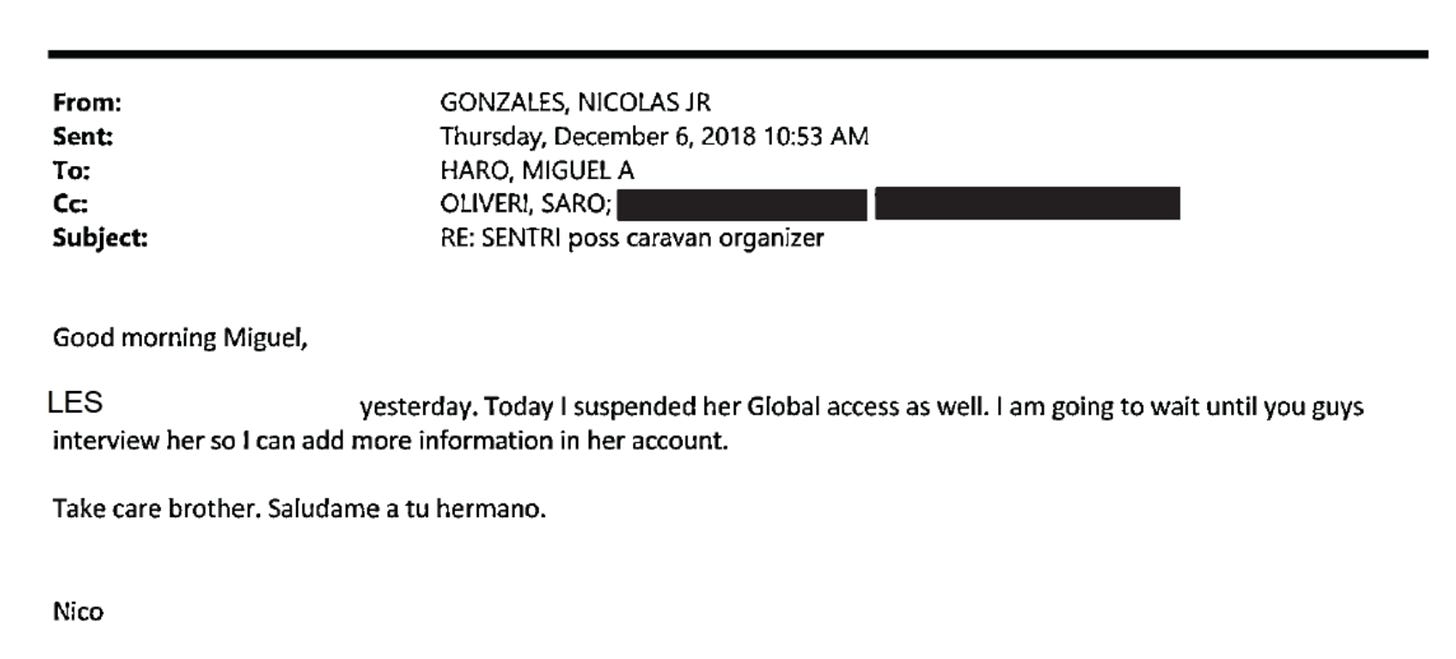

Operation Secure Line, Devereaux describes, was a “DHS-Pentagon initiative aimed at the 2018/19 migrant caravans that featured secret blacklists of suspected “organizers” and “instigators,” overwhelmingly w/out evidence those individuals were involved in a crime.” The program involved assembling dossiers on people who had not violated the law. One particularly revealing email exchanged discovered through FOIA reveals the level of coordination between agents about Pastor Dousa specifically.

This level of surveillance and monitoring of US citizens is made possible in part because of the juridical and political exigencies of border enforcement, which has long been constructed not just at the territorial margins of the country but also as the margins of many civil rights protections.

Katy Murzda at the American Immigration Council wrote recently about how the US-Mexico border is being used as a space of technological exception, where the US government is experimenting with technologies that would likely be viewed as reprehensible if used on citizens.

Most alarming, DHS has been “developing and testing robot dogs for use by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) at the U.S.-Mexico border” which I also wrote about a few weeks ago here, as well.

Murzda raises this concern: “Technologies that start at the border, such as aerial drones and license place scanners, are often later used in the interior of the country.” Murzda also describes the recent roll-out of CPB One, a program that uses “that uses GPS tracking and facial recognition” at ports of entry.

The Biden administration’s use of “smart border” language does not provide any reassurances.

We should take seriously the fact that data collected at the border is very likely to circulate much more widely than the border. Some of these data collection programs are made possible through the new—and growing—intergovernmental market for data that Bridget Fahey describes in her new article on “Data Federalism” in the Harvard Law Review.

Lahey describes how data collection and dissemination presents significant challenges to civil rights and privacy, most of all in the immigration context where “the federal government has for decades made the acquisition of data about noncitizens from state and local law enforcement a centerpiece of its immigration enforcement strategy.” We should add to Lahey’s statement that the line between information collection about immigrants and citizens is not a bright line at all (and, of course, Lahey knows this).

I highly recommend this interview with Lahey on the Lawfare Podcast.

Beyond the border, ICE’s use of Alternatives to Detention technology raises additional concerns about the amount of data the agency is collecting not only on immigrants but on citizens, as well.

ATD is typically associated with ankle monitors, those black boxes that migrants are forced to wear and which track geographic location through GPS technology. But ankle monitor use is entirely stagnant; all of the growth has taken place through the use of a smartphone technology called “SmartLINK” which was created by BI, Inc., the subsidiary of Geo Group. BI holds the contract with ICE for managing its ATD program. In fact, that contract is precisely why Geo Group snatched up BI, Inc. for half a million dollars back around 2011. SmartLINK uses facial recognition technology, geolocation technology, and other “case management” tools to track migrants who are awaiting their immigration court hearing.

I don’t think we need to be conspiratorial about this technology, but I do think we should recognize that we don’t fully understand the extent of SmartLINK’s capabilities now or how this technology will evolve going forward. And because BI is a private contractor, the company will be able to hide behind FOIA’s “trade secrets” exemption, preventing the public from, let’s call it, “monitoring the monitors.”

At the same time, the potential for smartphone surveillance and hacking by government or private actors has already proven to be a frightening reality. The Pegasus program developed by NSO Group in Israel is capable of hacking any smartphone in the world (no, I’m not exaggerating). NSO Group describes Pegasus as being able to “turn your target's smartphone into an intelligence gold mine.” (See the outstanding reporting on Pegasus by the New York Times here.) The FBI did experiment with Pegasus and ultimately decided not to allow it to be used in the United States. But that doesn’t mean that other defense contractors aren’t developing similar types of technology that could be successfully marketed to US agencies and integrated into various monitoring technologies (i.e. ATD?).

Currently, well over 110,000 migrants are monitored through SmartLINK with that number expected to grow to a few hundred thousand in the foreseeable future. ATD programs, much like post-incarceration programs for people with criminal convictions, does not just affect the individuals; it affects whole families and communities. Other members of the household of a person on ATD may have to provide their information to ICE, as well, allowing the agency to dramatically expand the identities and locations of people it monitors (although clearly not as intensively as the individual in the ATD program).

With names and addresses of entire households of people, ICE could then use its subscription access to services like LexisNexis that aggregate information from a variety of public records as well as through the kinds of data sharing programs that Lahey describes in her article (including fusion centers, data pooling centers like the National Crime Information Center, etc.).

To be clear: no, I don’t think that SmartLINK is Pegasus. All I’m saying is, there is an enormous unmapped landscape of data aggregation and surveillance technology that is still relatively new. I think we should be ready for an explosion of these types of technologies very soon, even if they vary in terms of their intensity and sophistication.

So let me end with Murzda’s concern, which I find entirely valid. These technologies—data collection and aggregation, surveillance, robot police dogs, Pegasus, smartphone monitoring—are being used first on noncitizens and even on citizens of color like Pastor Dousa. But the technology won’t stop there. I believe that in addition to existing concerns about what these technologies mean for immigrants and people along the border, we should also be concerned about how the “mission creep” tendencies of these technologies will affect everyone in the country.

In 2017, the Los Angeles Sheriff's Department was excited to announce that they had purchased their first police drone. How long until the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department purchases their first robot police dog?

THANK YOU FOR READING! 🙏🏼

If you found this information useful, help more people see it by clicking the ☼LIKE☼ ☼SHARE☼ button below.

A recent article in the Border Chronicle about Estefania Castañeda Pérez, a PhD candidate at UCLA, discusses her refusal to have her photo taken by CBP as she crosses from Tijuana into San Ysidro. Everyone assumes they have to comply, but it's not required. Of course, they can spoil your day if you refuse. CBP says all photos are discarded 12 hours later. I'm a tad skeptical. https://www.theborderchronicle.com/p/the-everyday-mistreatment-of-transfronterizo?s=r