Nicaraguan Migrants Arrive in United States in Record Numbers

After years of making up a small percentage of Central American migrants in the US, the number of Nicaraguans in the US immigration system has grown rapidly. Here’s the background and the data.

Until recently, Nicaragua stood out as a country that sent very few migrants to the United States in contrast to its neighbors—Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador—which, since 2010 or so, typically make up a very large percentage of people encountered at the border or in removal proceedings.

Since 2018, however, many Nicaraguans have been leaving the country and going primarily to Costa Rica but also now coming to the United States in higher numbers than before.

Late addition: After I published this post, I learned that President Biden had issued an executive order just this week to respond to the situation in Nicaragua. Biden’s order focuses on economic sanctions and does not appear to mention migrants or refugees, but I hesitate to say more without reading the full order and thinking through its consequences. Click here for Biden’s Executive Order on Taking Additional Steps to Address the National Emergency With Respect to the Situation in Nicaragua announced on October 24, 2022.

Let’s talk about what’s going on, starting with some historical background.

The most important thing you should know is that Nicaragua has a fascinating and tumultuous history, a history that pushes back strongly against the idea that the United States is (and has been) a unquestioned force for good in the world.

Even if we keep this short and start in the 1900s, we still have to contend with the U.S. military’s outright occupation of the country for the first third of the 20th century followed by the United States’s constant meddling in the country throughout the Cold War as Nicaragua become the site of proxy battles between communist and capitalist influences.

In the late 1970s, during the Carter administration, the US-backed leadership was overthrown and replaced by the Sandinistas (you may also see the abbreviation FSLN), a group that was created in the 1930s to resist the (then) occupation of the country by US Marines. Sandinistas are often described as revolutionary Marxists, but the truth is a bit more complicated, both because there were explicit differences between the Sandinistas and other Marxists at the time (surprise, surprise) and also because the origins of the principles behind the Sandinistas are not as simple as being a direct transplant of, say, the Russian flavor of communism.

In any case, one of the leaders of that resistance movement in the 1970s, Daniel Ortega, became president for several years following the revolution, got thrown out in an election in 1990, then returned to office more recently (we’ll come back to Ortega in a minute).

Opposition to the Sandinistas was led by the Contras and backed by the Reagan administration in the 1980s, specifically through the CIA. You may have heard of the Iran-Contra affair, the scandal involving the US’s illegal sale of arms to Iran for the purpose of smuggling money back to Nicaragua to support the Contras. Let’s not get too deep into historical debates here: both the Sandinistas and the Contras inflicted violence on their opponents, although the Sandinistas did implement some meaningful popular programs, as well.

Side note: For more information about the broad history of US and European intervention in Latin America, one classic source is Eduardo Galeano’s “Open Veins of Latin America.” Another favorite of mine is by Avi Chomsky who wrote “Central America’s Forgotten History” as part of her long-term research and activism in the region. Many more books are available specifically about Nicaragua.

As a result of the Reagan administration’s stance on Latin American politics, the US was involved in a series of destabilizing interventions in Central America in the 1980s. This had the predictable effect of leading to emigration, but this emigration just so happened to come shortly after the US had signed the Refugee Act in 1980 (one of the last things Carter did before leaving office). The United States had an obvious geopolitical incentive, therefore, not to recognize refugees fleeing the US-backed Contras (as well as other US-backed political groups in the region), because it would have been an admission that the regimes that the US supported were, in fact, committing human rights abuses.

The failure of US officials to recognize these refugees gave rise to the sanctuary movement along the US-Mexico border, which in practice meant taking in refugees not recognized by the US government, providing support through the asylum process, as well as organizing to prevent their deportation when needed. 99% Invisible has a great podcast about the sanctuary movement that often use in my course on immigration.

For anyone who got involved in immigration issues in the 1980s, all of this is probably fresh in your mind, much like those people who became mobilized by the Trump administration’s family separation policy more recently. But Nicaragua or even El Salvador may not be as present for a younger generation who is less connected to this Cold War history and this period of intense activism—even though its legacies persist. As a personal example, one organization that I’ve long worked with in Ohio, the InterReligious Task Force on Central America, was formed in the 1980s after two women from Cleveland, Jean Donovan and Dorothy Kazel, were killed in El Salvador.

This brings us up nearly to the present.

Daniel Ortega who, as I mentioned above, was previously ousted returned to power through elections in 2006, but later changed the constitution to abolish term limits and eventually appointed his own wife as vice president. Several lines of resistance converged to produce a new stream of revolts starting in April 2018 in Managua and have continued more or less to today with varying intensity. Reports suggest that between 300-500 protestors were killed relatively early on by police and at least two police officers were killed, but Ortega remained in power.

For more information: I want to thank Jennifer Goett for taking the time to talk to me about the situation in Nicaragua and for her work. See “¡Matria libre y vivir!: Youth Activism and Nicaragua's 2018 Insurrection” and “Beyond Left and Right: Grassroots Social Movements and Nicaragua’s Civic Insurrection”, both available on her Academia page above. For another useful analysis of the situation, here’s an open access article assessing the protests and the government’s response.

By 2020, 100,000 people had fled the country and by February 2022, the UNHCR reported that at least 150,000 Nicaraguans had fled to Costa Rica. The Migration Policy Institute acknowledges that Costa Rica is generally welcoming towards Nicaraguan refugees, but published a report examining more subtle barriers that Nicaraguans face in the country. In contrast to the US’s response to refugees, Costa Rica is actually moving to regularize the status of what reports say are about 200,000 Nicaraguan migrants in the country.

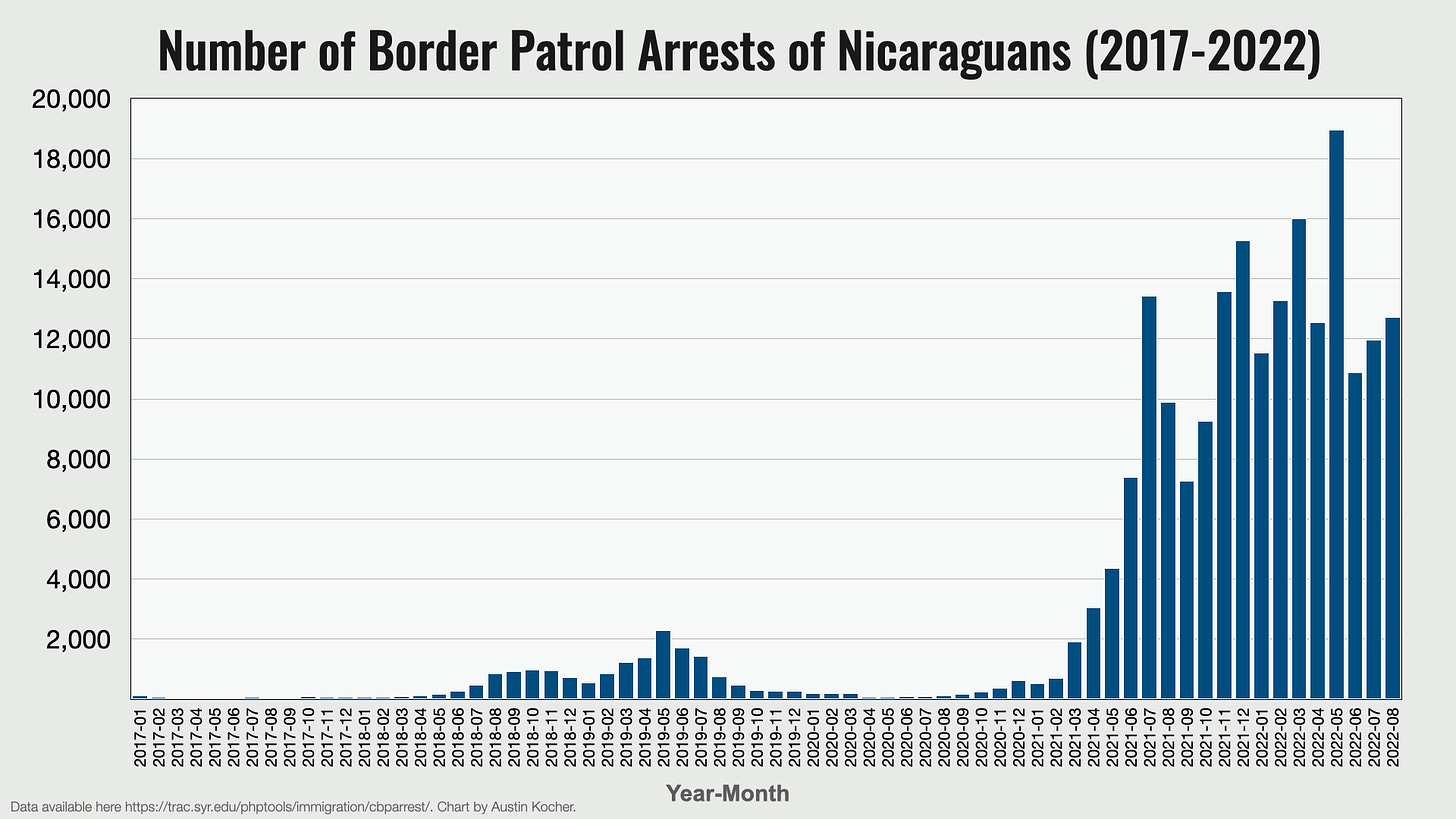

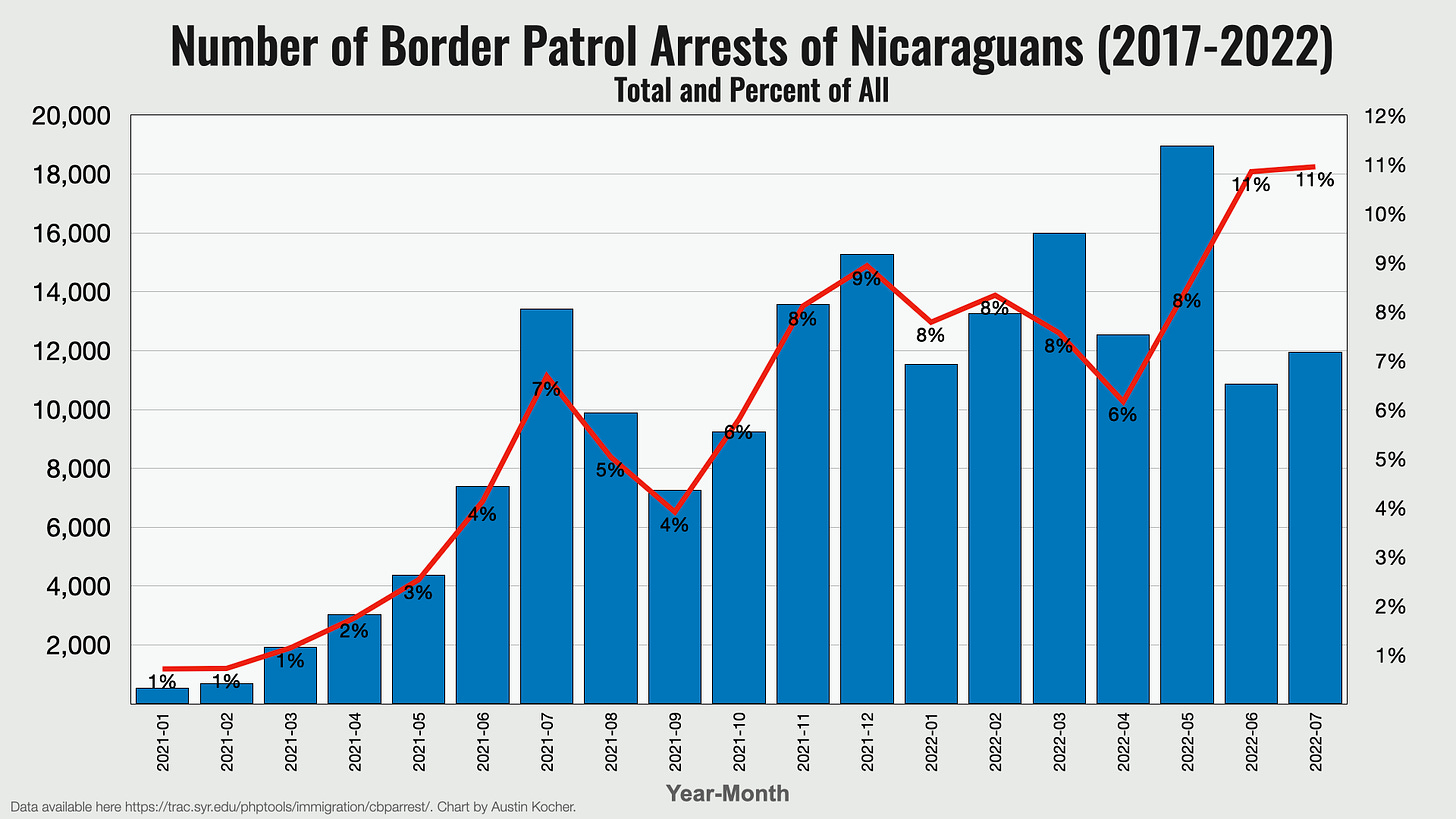

Increasingly, however, Nicaraguans are also coming to the United States likely motivated by some combination of political and economic instability. Like my recent Substack post and Twitter thread about Venezuelans, I wanted to provide as much data about the recent growth of Nicaraguans in context. But I want to emphasize two things here before we go into the data.

First, although this is a longer-than-normal post, I hope it illustrates the importance of understanding the geographic and historical context of migration to the United States. So often, media reporting starts at the US-Mexico border rather than in sending countries. This is a political and moral failing. Context is crucial. Context is everything.

Second, although it’s true as I often say that any political conflict in the world will eventually show up in US immigration data, I am also quick to emphasize that developing countries typically absorb the largest numbers of refugees despite having fewer resources. This is true here, too. Costa Rica is not really a poor country, relatively speaking, but with a population of about 5 million (about half the size of New York City), accepting 200,000 refugees is 4 percent of the population and would be the equivalent of the United States accepting 12.8 million refugees.

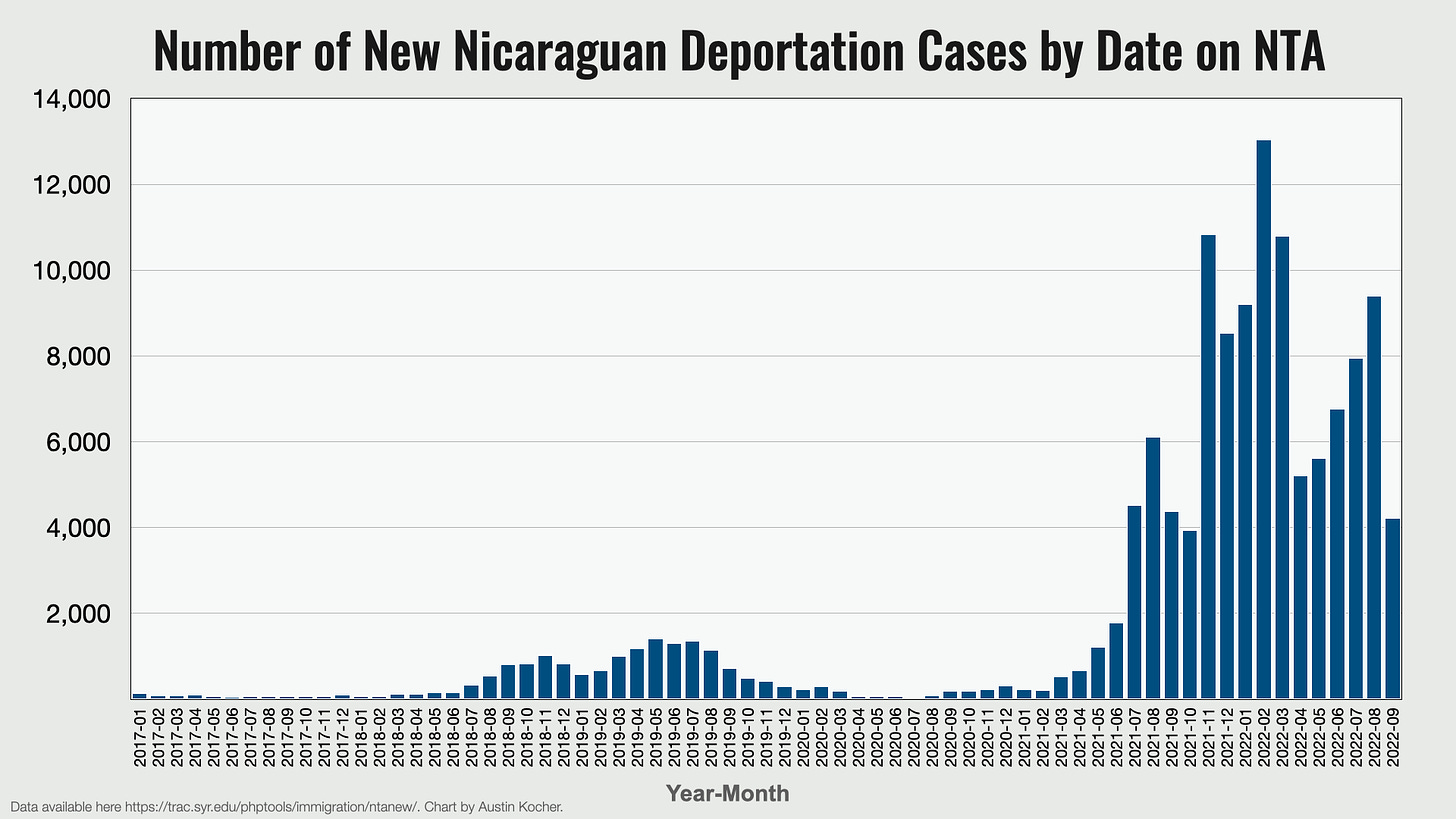

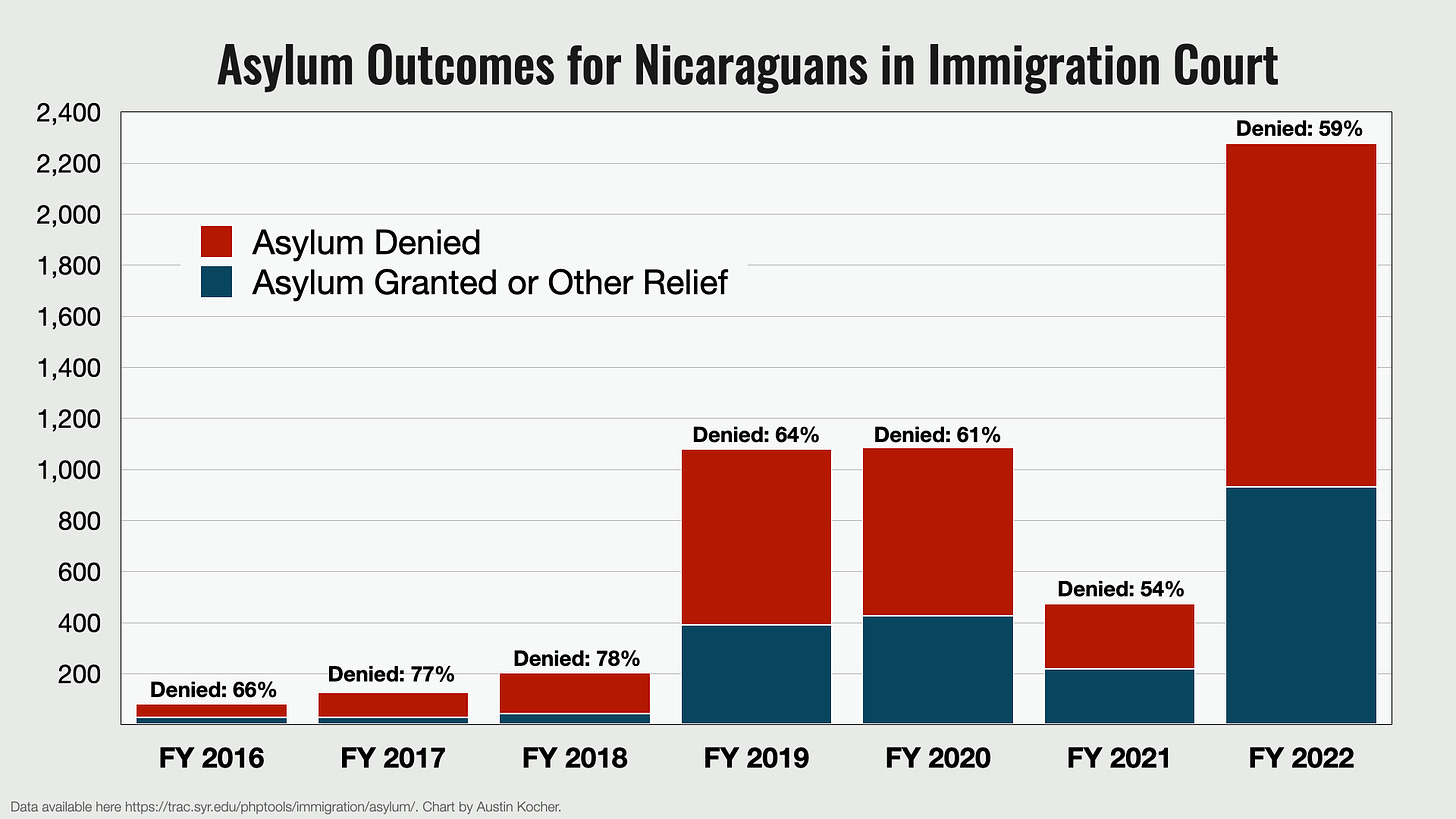

With all that said, here’s the data on the recent remarkable increase of Nicaraguans coming to the United States and getting caught up in various parts of the US immigration system.

Support public scholarship.

Thank you for reading. If you would like to support public scholarship and receive this newsletter in your inbox, click below to subscribe for free. And if you find this information useful, consider sharing it online or with friends and colleagues.

In Brownsville this past May, most of the people we welcomed were from Nicaragua, with Cuba a distant second. I had heard that Nicaragua would accept only a small number of its people deported from the U.S., maybe a couple of hundred per month.

Thank you for this- great work!