Saying the Thing Out Loud: Trump's Latest Refugee Order Embraces White Victimhood

While the refugee system is suspended for the rest of the world, a new order from President Trump creates a special exception for white South Africans facing "race-based discrimination."

President Trump indefinitely suspended the United States refugee system on the first day of his presidency citing all manner of unsubstantiated claims about national security and the country being “overwhelmed” by refugees.

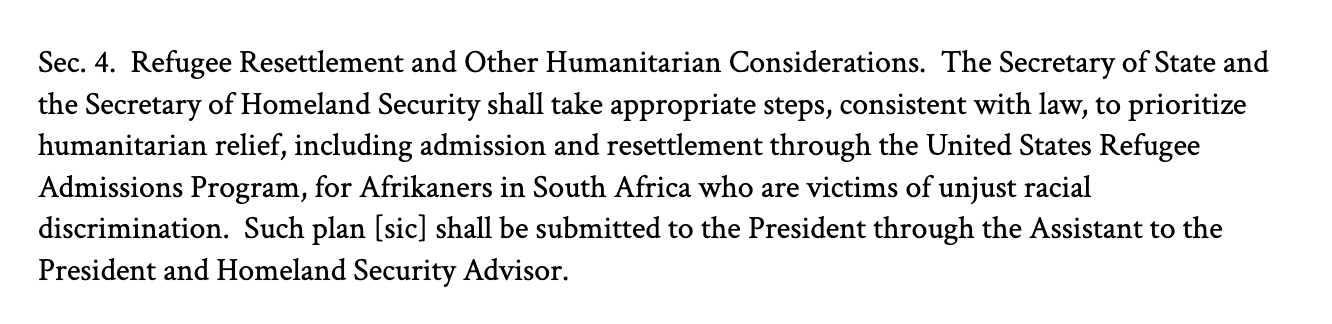

But today, Trump signed a new executive order that lays bare the underlying racial dimensions of his nationalist policies. At a time when the the United States is deporting Black and Latino immigrants to politically and economically unstable countries, Trump has instructed his agencies to prioritize the resettlement of white “refugees” from South Africa, aka “Afrikaner refugees”.

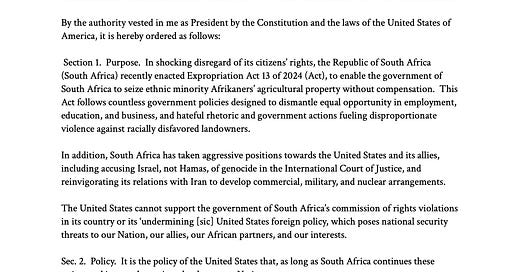

Don’t take my word for it, here are the two crucial excerpts from his EO. Trump claims that Afrikaners are “victims of unjust racial discrimination”, including “property confiscation.” What is this all about? Is this real? How should we think about this? There are several key things we need to discuss, so let’s get into it.

Help me continue to publish research reports like this one with a fast turn-around. This newsletter is only possible because of your support. If you believe in keeping this work un-paywalled and freely open to the public, consider becoming a paid subscriber. You can read more about the mission and focus of this newsletter and learn why, after three years, I finally decided to offer a paid option.

The Role of Race in the US Immigration System

Let’s just state the obvious: this executive order puts into writing the kind of unapologetically preferential treatment of white people that defined far too much of American history. Whatever the validity of the concerns of white South Africans, most thinking people will draw an unambiguous contrast between this EO and the other EOs that not only shut down the refugee process for other migrants, but encourages DHS to actively deport asylum seekers and potentially refugees back to places where they could be killed.

For years, the US immigration system has operated with a series of implicit racial hierarchies and racially disparate outcomes. But it was not that long ago that the immigration system was saturated with institutional racism from top to bottom. The easiest entry point into this history is with the figure of Madison Grant.

Grant was a wealthy New York environmentalist and eugenicist who made it his life’s work to twist science into supporting his view—and the views of many Americans—that whites (certain whites, anyways) belonged at the top of a hierarchy of human worth with black and indigenous people at the bottom. A knock-off copy of his book “The Passing of the Great Race” sits on my shelf as a vile testament to the dangerous ideas that shaped the country we live in, but also to the specific influence that Madison Grant had over the writing of the 1924 Immigration Act. The 1924 act wasn’t only the first attempt to write a comprehensive framework of immigration laws, it was also a project to limit “undesireables” (non-whites, people with disabilities, people who didn’t agree with these political ideals) and facilitate the flows of northern European whites (“Nordics”, he called them) into the country.

I first came across Madison Grant in the research library of the US Citizenship and Immigration Services agency in Washington, D.C., when it was located across from Georgetown University (it has since moved). But it wasn’t until my colleague, political geography and border scholar Reece Jones published White Borders: The History of Race and Immigration in the United States from Chinese Exclusion to the Border Wall a few years ago that I finally read a more complete and succinct account of Grant’s role—and the role of race more broadly—in shaping our immigration laws. You might also read Reece’s op ed in the New York Times here for a shorter take.

I won’t reiterate all of Reece’s points here, though I encourage you to get his book if you’re interested. Nor is he the first one to make them. Scholars of immigration history have long recognized that race plays a key role in shaping immigration policies. Frederick Douglass’s Composite Nation, written and delivered as a traveling speech in 1867 feels shockingly modern. Years ahead of the Chinese Exclusion Acts, Douglass boldly decries the fear-mongering over Chinese immigrants, declares that immigrants are a source of strength for the country, and calls for the nation to embrace what he calls “absolute equality among the races”.

What most scholars in recent decades have also noted—and which Reece notes in his book, too—is that explicit racial categories in the law have been supplanted by increasingly implicit naming of race as a factor. This often means that the way we assess the role of race is often through how different nationalities, which are sometimes proxies for racial identity, shape the treatment and experiences of different migrants. In a previous post (below), I compared the treatment of Ukrainian and Haitian asylum seekers arriving at the US-Mexico border to show how and why immigrant rights advocates often point to differential treatment as evidence of the constitutive role of race in our border enforcement practices.

Here’s what I’m trying to say in a nutshell: race has played a central role in our system, but it has been a long time since we have seen so explicit of a reference to whiteness as a preferential category that, to me and others in this field of study (and many of you, I’m sure), this EO feels like they aren’t just saying the thing out loud—they are screaming it.

But why South African? And why now? Does it have anything to do with Elon Musk being South African himself?

South African Apartheid in a Nutshell

The short-term backdrop for Trump’s EO is a recent law in South Africa that allows for some land redistribution from white South Africans, or Afrikaners, to non-white people in South Africa who were disenfranchised through years of racially restrictive laws that limited land ownership. [Edit on 2/8/25: I should have said that this is just one element of the backdrop of the EO. South Africa’s position on the war in Gaza and Musk’s unelected influence in the White House are others that I don’t get into here.]

Justice-minded people of a certain age will need no explanation of South African apartheid, because it defined several generations of national and international activists, from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to Ghandi. In fact, Ghandi began his transformation from lawyer to non-violent leader in South Africa as one of the members of the Indian minority who were affected by the country’s race laws. But not everyone reading this will feel so personally connected to that history, so let’s take a moment to revisit this brutal yet all-too-familiar story of violent racial segregation.

As I said, South African Apartheid was a defining social justice concern for the global community for years. Apartheid was a legal and geographic system of racial segregation that regulated nearly all aspects of life in South Africa based on the racial identity of each person. At the top where whites (Afrikaners), with people labeled as Colored (yes, Colored), Indian, and Black (distinct from Colored) in a hierarchy that affected where people lived, who they worked for, access to the ballot box, and so on. Apartheid simply means “apartness” in Afrikaans, but we might also translate it as segregation to avoid the euphemism of the transliteration.

Although the formal policy of Apartheid began when the Nationalist Party came to power shortly after World War II, racial discrimination and segregation were decades—event centuries—in the making. It began with the colonization of the southern tip of Africa by Dutch settler colonialists who developed a distinct cultural identity as Afrikaners. Later, as white nationalist movements swept across the globe in the late 1800s—the same period that nativists created the US’s first racially restrictive immigration laws under the Chinese Exclusion Act—white South Africans also began to use the power of the state to curtail rights for minorities and enrich themselves politically and financially.

Thus, by the time that the Nationalist Party took over in the late 1940s, the legal and political framework for Apartheid was well-established. Nevertheless, things got worse. Pass laws required non-whites to carry identification to simply travel throughout the city and restricted where they could go. Black South Africans were restricted from access to education. Crucially for our purposes, the Natives Land Act, passed in 1913, restricted land ownership almost exclusively to whites and left a long legacy of dispossessed Black South Africans that continues to this day.

Apartheid formally ended in the early 1990s alongside a wave of seemingly progressive political successes, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the activists in Tiananmen Square. Nelson Mandela became the country’s first Black president in 1994. Throughout the 1990s, South Africa engaged in what many regard as a test case in careful and intentional social change through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that believed in a kind of national reunification rather than retribution—although obviously not everyone saw it that way. Some critics were angry that there were so few consequences for the white minority that perpetrated Apartheid (see also Nazis left in government in West Germany after World War II) while many Afrikaners denied any guilt or responsibility at all.

Just an aside: I have to give credit to Kevin Cox, a political geographer at Ohio State (now retired) whose graduate seminar on the political geography of South Africa is the basis for this oddly specific background knowledge.

This brings us up to the present day and the context for the recent law in South Africa that is permits some level of land redistribution as part of the country’s ongoing process of addressing the decades—indeed, centuries—of racist and colonialist wrongs inflicted upon Black Africans. I can’t play expert on the details of the South Africa law, but it will not surprise you to learn that Trump’s representation of this law in his EO does not square with competent reporting I found this evening. What matters more for now is that you know the context for the law rather than the full details of the law itself.

Afrikaner Refugees… But how?

Now that we’ve touched on a history of race and the context of Apartheid, I want to make a final point about the EO. It feels like it’s written by someone who doesn’t understand the refugee system. I’ll let the immigration lawyers take their shots, too. But let’s just say, if Afrikaners are going to come through refugee resettlement, it still means that they have to meet the definition of a refugee.

Or if Trump wants them to come through the asylum process, they will also have to meet those criteria. (Remember my post about nothing being “automatic”? Worth revisiting.) And I’m just not totally sure that there are all that many people getting their property confiscated by the South African government or that, even if some people are, that they legally qualify as a refugee or asylee solely for that criteria.

You don’t get asylum or refugee status just because there’s a law in your country that might possibly affect you or someone like you someday. The attorneys are going to have a field day showing a litany of denied asylum cases that look exactly like this (but in Latin America).

I’m sure we’ll see more commentary on this, as well as law suits that will further elaborate more rigorous critiques than I’m able to muster in the train back from NYC to Baltimore. Stay tuned.

The “Afrikaner Refugee” EO

The entire executive order can be found below in a cleaned-up format that is easier for reading and annotating. The official announcement is on the White House website.

The rest of the immigration-related executive orders are available to download in any format from the public Google Drive folder here. (I’ll admit that I might have missed a few recent EOs that pertain to immigration; if I have, please let me know.)

Consider Supporting Public Scholarship

Thank you for reading. Please subscribe to receive this newsletter in your inbox and share it online or with friends and colleagues. If you believe in this work, consider supporting it through a paid subscription. Learn more about the mission and the person behind this newsletter.

A comment to the South Africans here: I don’t think anyone is discounting the violence and anti-white laws in South Africa. I’m sure it’s horrifying to live as people have described. I think the point is that governments and militias all over the world are doing horrifying stuff to people, yet the mechanisms we have in this country to protect people from harm have all been shut down. Laws have been passed to take away legal status from and deport brown and black people. The situation in Haiti is horrifying. Same with Nicaragua and Venezuela, the Congo, Myanmar. Yet in the midst of all of these despicable actions, one group has been singled out for a protection that legally they can’t access, and that’s white people from South Africa. We have to ask ourselves why single out this one group in a world where people are harmed on a daily basis? (My answer is Elon Musk)

White settler colonialism... It's still with us in the 21st century. The pearl clutching in the comments here is pathetic. Whites should learn what they as invading colonizers inflicted upon indigenous peoples by stealing their lands and resources would one day come back to bite the children of white invaders in their backsides. But racists seldom learn moral lessons, I'm told.