Speaking of Nationalism: New Policy Makes English the Official Language of the US

President Trump's new executive order making English the official language of the United States has its roots in the anti-immigrant movement and 20th Century nationalism. This time it's personal.

Last weekend, President Trump issued an executive order to make English the official language of the United States, capping off decades of lobbying from anti-immigrant groups eager to foment non-issues as part of our country's broader culture wars.

Unlike some of Trump's other executive orders on immigration, the specific directives in this one are somewhat vague. The order paves the way for agencies to reduce or eliminate non-English language services and materials, which could have significant implications for Americans with limited English proficiency. As if leading by example, the White House has already removed the Spanish language version of its website previously hosted at whitehouse.gov/es/.

For a few hours the button at the bottom of the page said simply “Go Home,” implying that Spanish speakers should leave the country—but this was changed by Sunday morning.

However, the order neither orders agencies to take, nor prohibits them from taking, any specific action. The order instead leaves it up to agency heads to decide when and how to implement this vague order, which means that we might see already existing non-English resources gradually disappear and fewer new non-English resources produced across the federal government.

I had hoped to share a quick analysis over the weekend when the order came out. Instead it has taken me several days of reflection to identify why this executive order has been gnawing at me in a way that others have not. I think it's because the deeper meaning behind this executive order has less to do with specific institutional changes and more to do with the epic history of nationalism that continues to unfold with catastrophic consequences in our current moment. Perhaps it is also because my own perspective on the world has been profoundly and gratefully shaped by learning other languages and by my personal relationships within non-English speaking communities.

In this issue, I want to share the personal and human side of what is called "linguistic chauvinism", or the belief that certain languages and dialects are superior to others, and emphasize how linguistic chauvinism has been weaponized by nationalist movements over the past century both abroad and at home in the United States. The fact that Trump's English language EO is light on administrative directives lends support to the argument that the order should be understood primarily as a symbolic gesture towards further stigmatizing non-English languages and speakers many of whom are immigrants.

Like so much of "culture war" topics, this order is an ineffective solution to a made-up problem. Allow me to start by sharing some of my own experiences, then discuss what the order says and does not say about English as the allegedly "official" language of the United States.

This newsletter is only possible because of your support. If you believe in keeping this work un-paywalled and freely open to the public, consider becoming a paid subscriber. You can read more about the mission and focus of this newsletter and learn why, after three years, I finally decided to offer a paid option.

Language is Personal and Political

Language is my first love. My intellectual development and, later, my academic research, has always been rooted in an abiding interest in the power of language as a paradoxically material and immaterial force in the world.

I spent my formative early adult years in Puerto Rico, first with the U.S. Navy and then, both during and after my enlistment, as a teacher at a school for children who were Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (HOH). I was a linguistic outsider twice over: first as a Spanish language learner and second as a learner of American Sign Language (ASL). But my identity as a white abled person living in what Trías Monge calls the "oldest colony in the world" meant that I did not face the same social and economic consequences for my lack of fluency in ASL and Spanish as others did for their lack of fluency in English.

This lesson about the relative social prestige of various languages and the perceptions of one's language fluency is a lesson one learns very early in one's language journey—at least if you are learning language in the real world. Each of my students experienced moments of embarrassment, disconnection, and even harassment for the language they used. Often this was fueled by the misperception that ASL (and other signed languages) are not real languages (which they are). Even with my relative privilege, I can recall my own times over the years stumbling through a sentence in Spanish or in German while holding up the line behind me at a restaurant or holding up a conversation at a table where everyone else is more fluent in the language than I was.

I developed an interest in connecting people across languages. After I returned to Ohio, I worked for many years, though only part-time throughout graduate school, as an ASL-English interpreter in settings that ranged from academic lectures to doctor's office visits to shift meetings at the nearby FedEx distribution center. My work as an interpreter was defined by normalizing cross-linguistic communication, which required me to work out, in real time, how to capture not just the words but the essence of what people were trying to tell each other and create a sense of authentic mutual understanding. Perhaps this experience is also what drives me to connect academic research with a broader community. Even within a common language, unexplained jargon, political ideologies, and institutional norms limit our ability to communicate authentically with one another.

As sociolinguists show us, the paradox of language is that it is deeply personal and socially interdependent at the same time. Language cannot exist without a community of speakers who establish its rules. Yet, at the same time, language shapes how each of us experiences and expresses our understanding of the world. Language is simultaneously a source of our vulnerability and the basis of community.

The powerful role of language in shaping human society also makes language a tool for despotism. Years after I experienced first-hand the complex relationships between ASL, Spanish, and English on the island of Puerto Rico, I would learn about the long history of nationalist language policies passed under the auspices of cohesion and unity. The laws that made Afrikaans and English the official languages of South Africa were supported and passed by the same National Party that implemented South African Apartheid. The National Socialists in Germany (i.e., the Nazi party) created strict German language reforms that sought to remove "non-Aryan" influences, including English and Yiddish, from the language while also implementing German-only laws in conquered territories. Stalin mandated Russian language reforms that sought to squash local and regional languages and remove foreign influence. Wherever authoritarian leaders take power—Mussolini, Mao, Franco, Pot, Hussein—strict language policy follows.

The United States is not without its own sordid history of English language policies. Native Americans are well aware of the violent history of forced assimilation, a central component of which was the prohibition against children speaking their native languages upon threat of corporal punishment. As a result, most indigenous languages in the United States and around the world are endangered, with nearly half of all spoken languages today likely to die out in our generation. American Sign Language flourished for much of the 1800s until Deaf people faced similar attacks starting in the late 1800s during a wave of strongly anti-immigrant sentiment that viewed non-English languages, including American Sign Language, as un-American. An entire generation of highly educated Deaf teachers were fired, replaced by hearing teachers who punished children who moved their hands instead of attempting the mostly impossible task of speaking English. The cultural damage to the Deaf community lasted for decades.

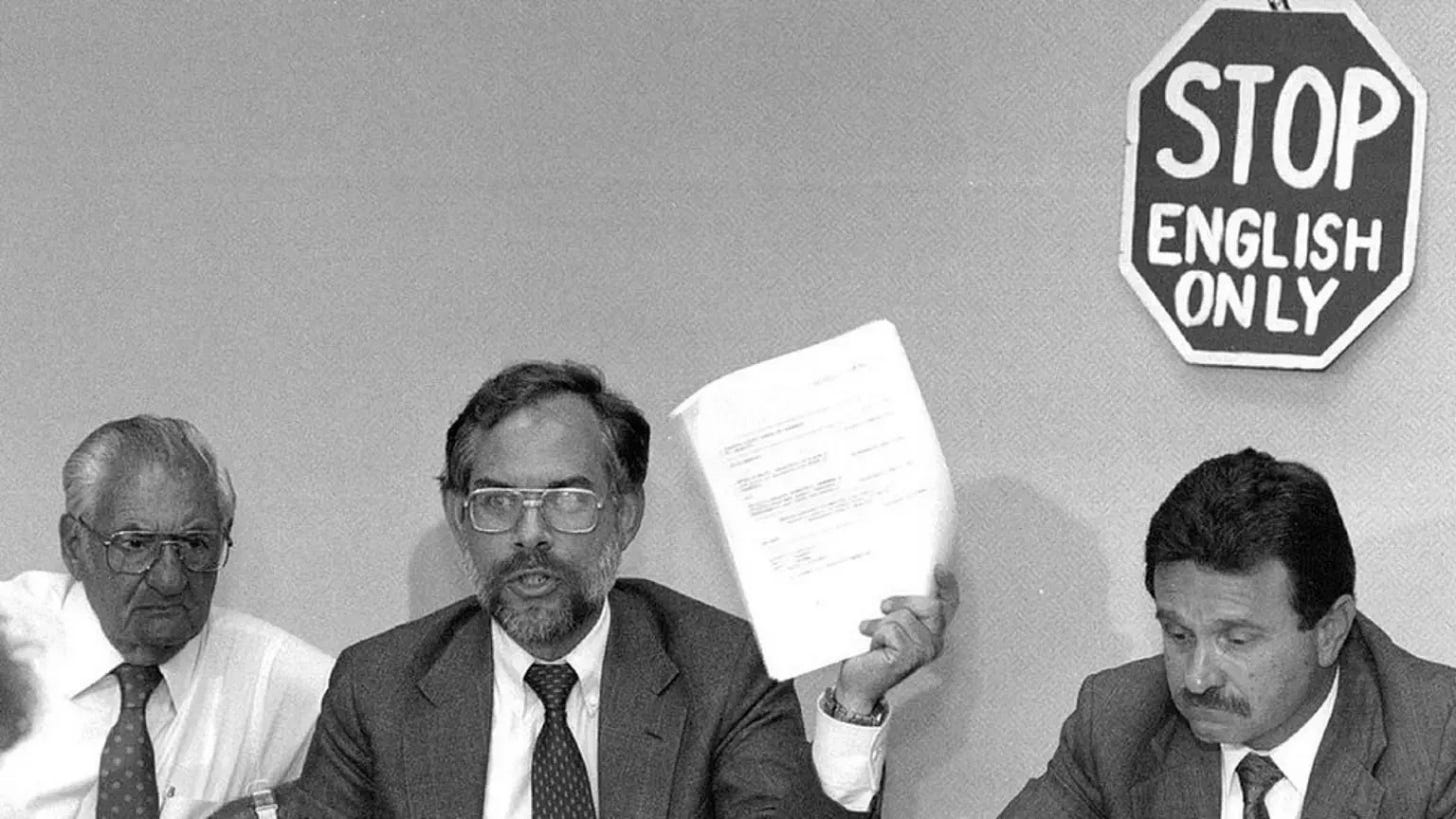

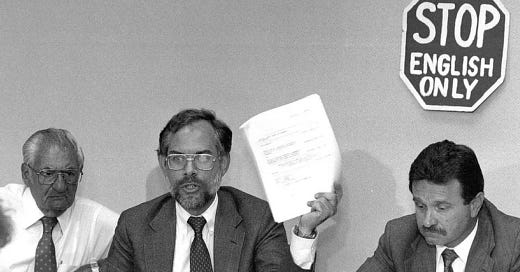

Since the 1980s, a decade in which much of the anti-immigrant movement today put down roots, the English-only movement has sought to make English the official policy of the United States. Incensed by the inconvenience of needing to "press 1 for English" or hearing Spanish spoken in public, advocates of making English the official language have been hard at work to pass state laws making English the official language, but they have always aspired to more. As decades of research shows, English language adoption in the United States is a mostly natural intergenerational process. No one needs to be reminded of the importance of learning English; the overwhelming dominance of English in the United States and the stigma against non-English fluency and prejudice against accents provides more than enough social incentive. Unsatisfied with this, however, the English-only movement continues to press on for still more laws and policies to regulate language use and, by extension, language users.

In addition to the many state laws making English the official law of the land, legislative attempts have been made to make English the official language of the country by law. The following are just two examples. The Language of Government Act proposed in Congress in 1995 would have mandated English as the official language of the U.S. government. In 2023, J.D. Vance introduced the English Language Unity Act when he was still a Senator from Ohio. Neither bill passed but both bills laid the groundwork for Trump's English language executive order. Like Trump's order, both of these bills are short and polemical to the point of being almost pointless and they contain so many exceptions as to prove the futility of having an official language in the first place.

One final point before we look at Trump's English language order. The English-only movement, proposed legislation in the past, and Trump's EO all emphasize English. The real message that they do not say (and could not say for equal protection reasons) is that each of these policies are about not-Spanish. Even though Spanish is as native to the territories of United States as English (if not more so), the association between Spanish language speakers and immigration, especially undocumented immigration, is so strong in the minds of many Americans as to make them indissociable. And even though English language policy does affect many people, including French speakers, Creole speakers, indigenous language speakers, and Deaf people who use ASL, make no mistake that the primary target here is Spanish. The underlying motivation for English-only policy is wrapped up in immigration invasion rhetoric and the great replacement conspiracy theory, all of which focus heavily on Latinos.

Trump's English Language Executive Order

The text of the order follows the format I laid out a few weeks ago: a polemical and largely unsubstantiated introduction followed by more specific directives and pro forma notes at the end.

The order titled "Designating English as the Official Language of The United States" begins by claiming that "English has been used as our national language" since our founding and gives the example that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were written in English. The order then concludes:

"It is therefore long past time that English is declared as the official language of the United States. A nationally designated language is at the core of a unified and cohesive society, and the United States is strengthened by a citizenry that can freely exchange ideas in one shared language."

The order continues by emphasizing the social and economic benefits of English for new citizens because it "helps newcomers engage in their communities, participate in national traditions, and give back to our society." The introduction acknowledges immigrants who have learned English and passed it on to their children, then concludes with this purported call to social cohesion:

"To promote unity, cultivate a shared American culture for all citizens, ensure consistency in government operations, and create a pathway to civic engagement, it is in America’s best interest for the Federal Government to designate one — and only one — official language. Establishing English as the official language will not only streamline communication but also reinforce shared national values, and create a more cohesive and efficient society."

After the polemical introduction, the order accomplishes two things. First, the order rescinds a Clinton-era order called "Improving Access to Services for Persons With Limited English Proficiency" (EO 13166)—and order which already emphasized the importance of learning English but included a directive for agencies to make sure that limited English proficiency was not a barrier to agencies achieving their goals. Second, the order basically tells agency heads to do whatever they want when it comes to producing non-English materials. The order specifically says that agencies are not required to anything differently and they are not prohibited from producing non-English language materials.

Research and writing tip. The Federal Register (FR) maintains official copies of executive orders issued by U.S. presidents using a five-digit sequential numbering system (e.g., EO 12345). Except for the short delay between when the president issues an EO and when it is added to the FR's website, link to and cite information on the FR rather than linking to the White House since those links will degrade rather quickly. Federal Register: Trump's Executive Orders.

The Practical Effects of Trump's Executive Order

As you can see, the substantive part of the order is anti-climactic on the surface since it neither compels nor prohibits agencies from doing anything. It is possible that agencies will stop producing new non-English materials or, as the White House has already done, begin removing non-English materials immediately. It might also mean that agencies will choose to stop providing non-English interpreters in certain situations. Implementation of this EO will depend on how aggressively Trump's political appointees enforce an English-only policy and whether existing laws require materials to be available in other languages.

This order could make it even harder for immigrants to get access to legal resources when they are held in detention or going through removal proceedings in court. Already many local jails and detention centers across the country fall short on hiring bilingual staff and providing documents in Spanish and other non-English languages. This could further embolden federal and local agencies to refuse to provide resources to immigrants in any language other than English, which would effectively deny them due process.

The order could have wider effects beyond the immigration system. It could lead to cuts in education funding for programs that provide teaching and resource in Spanish or other languages. The order could also lead to less voter information in Spanish, although, as Daniel Olson noted, this is perplexing since Trump invested heavily in Spanish-language media on the campaign trail largely to his own electoral benefit. There is much about this order that will only be worked out in the coming weeks and months.

In my view, the deeper meaning of this executive order cannot be read from the text itself, but should be understood from the larger and more controversial role that language policy has played in the history of nation-building within the United States and around the world. This order is the culmination of years of anti-immigrant organizing that uses language use as a way of governing language users. I don't like it. I have seen first-hand the ability of language to bring people together and foster curiosity about the world, and I have seen how language chauvinism divides us and fosters fear.

No one needs to be reminded that English is the dominant language in the United States. This order does not simply recognize this reality, as advocates claim, it also creates a new permission structure for prejudice toward people who do not speak English fluently or speak with an accent. Worse, this order is part of a dangerous legacy of nationalist policies that attempt to create unity through conformity and subjugation, rather than accepting our differences.

What can you do about this order? Learn another language or even just a few words. Be patient with people who do not speak English fluently. I saw a t-shirt once that said "monolingualism is curable: take a foreign language." At a time when things feel very heavy, finding a new way to connect with others across language barriers might be the kind of hopeful project that will keep you going through hard times.

Consider Supporting Public Scholarship

Thank you for reading. Please subscribe to receive this newsletter in your inbox and share it online or with friends and colleagues. If you believe in this work, consider supporting it through a paid subscription. Learn more about the mission and the person behind this newsletter.

Non-immigrant Americans who are hostile to other languages are the same people who make no effort to speak the local language when they travel abroad.

(I worked with deaf junior college students many years ago and learned a little ASL. ASL is indeed a "language" and boy, oh, boy could those kids crank up their speakers to feel the bass line!)

I'm disheartened by all the racist claptrap that is trying to masquerade itself as an "executive odor" (as they are certainly smelly).

My experience tutoring Bosnian immigrants gives evidence as to why not everyone who becomes a US citizen will ever be English fluent (or should). I remember an older Bosnian refugee who was coming to our tutoring sessions for help learning English. She came into the country with her adult children and grandkids, and she wasn't working outside the home, but she was providing much needed childcare and housekeeper care to the younger generations who were speaking English at work and the youngest who were all attending public school in English.

But to take the citizenship test, this very nice lady had to be able to show "English proficiency" because she wasn't quite old enough to skip that part. Let's say we all gave it our best shot, but the poor woman couldn't learn English well... We figured that she had never had much schooling in her own language (and I wondered if she was actually learning disabled) so the whole learning process was very difficult for her. The more I learned of her story, the more I felt that she also suffered the PTSD almost all the Bosnians had from witnessing the Serbs shoot their husbands, sons, fathers, brothers, neighbors, etc., in front of their eyes and throw the bodies into ditches. So mental and psychological barriers would keep this very nice lady from ever learning more than "Hello!" and "Thank you!" in English.

Will Trump's racist E.O. eventually make it impossible for persons who had suffered so much to become US citizens because of language acquisition difficulties? This is truly a human rights violation, IMO.