Ukrainians Granted Temporary Protection in Europe and US, Afro-Ukrainian Refugees Report Racism, the High-Tech Side of the War, and More

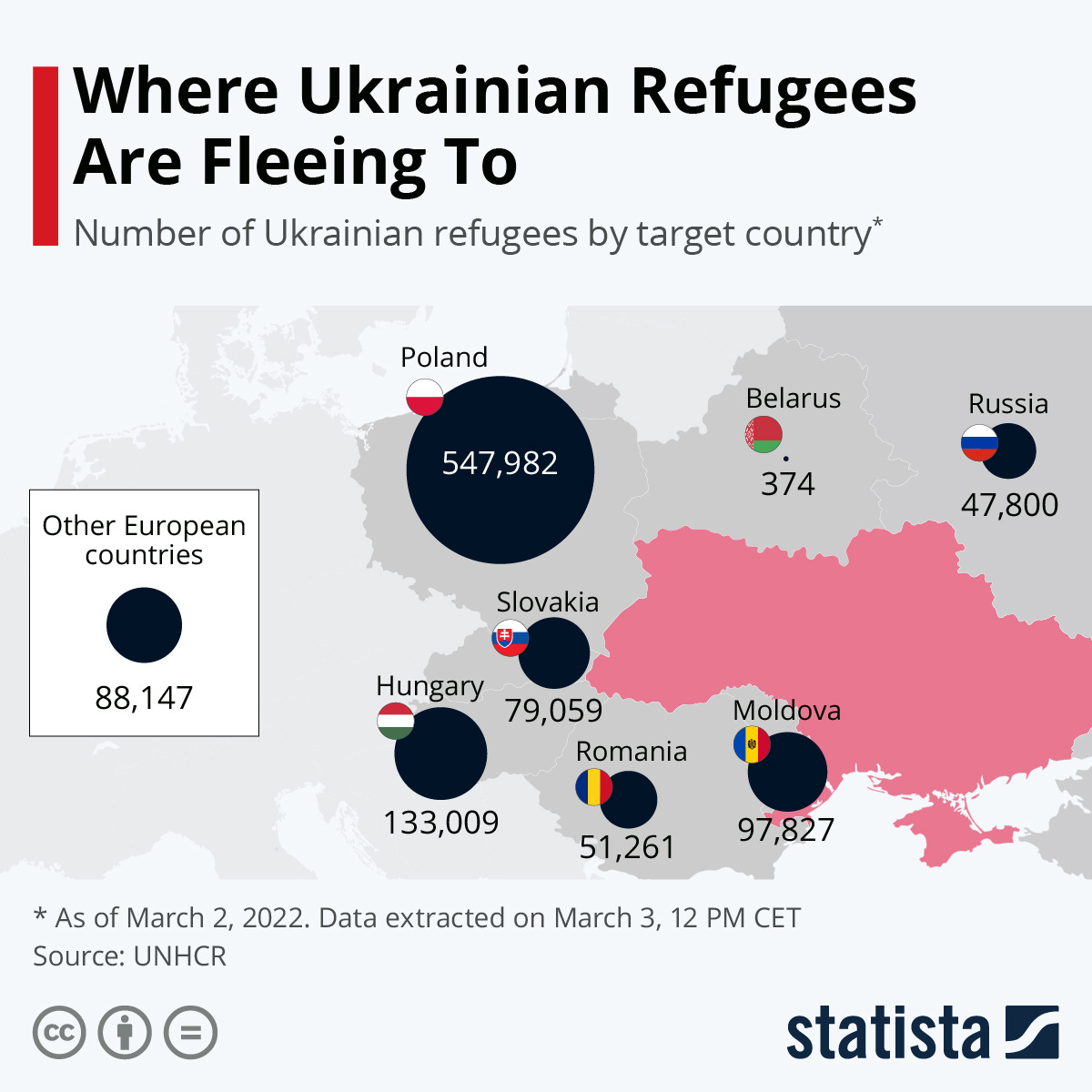

As of Wednesday morning (March 3, 2022), the UNHCR announced that more than 1 million people in Ukraine had fled the country due to escalating war as a result of Russia’s military invasion of that country.

The following newsletter highlights the key issues surrounding refugees, mobility, and law that are unfolding as a result of the war. I want to be clear: I am not an expert on Ukraine. But as a geographer and immigration scholar, the crucial role that human migration and mobility is playing at this historical juncture is worth tracking and putting in perspective.

You are invited to be a part of this conversation by posting any corrections, additions, or different perspectives in the comments.

Biden Grants TPS for Ukrainians

Yesterday evening the Biden administration granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Ukrainians. This means that Ukrainians who are currently in the United States will not be forced to return to Ukraine, including those who are currently facing deportation.

Note that TPS is not the same as being granted asylum or refugee status. TPS only applies to people already inside the United States, not to people traveling to the United States. Refugee status is determined before someone travels to the country where they are resettling and typically requires a longer processing time. Asylum is a process for being recognized as a refugee once that person arrives at the borders of a country or once they are already inside a country. Unlike asylum or refugee status, if granted, TPS is intended to be temporary and does not put a person on a path to citizenship.

The Center for American Progress estimates that TPS could benefit up to 96,000 Ukrainians living in the United States without citizenship, including perhaps 27,000 undocumented Ukrainians.

TPS would also apply to Ukrainians currently facing deportation. As of the end of November 2021, nearly 4,000 Ukrainians were facing deportation in the immigration courts.

US Citizenship and Immigration Services identifies other countries that have already been granted TPS, though qualifying criteria vary from country to country: Burma (Myanmar), El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. The day before granting Ukrainians TPS, DHS Secretary Mayorkas also extended TPS to Sudan and redesignated South Sudan for TPS.

Notably absent from this list is Afghanistan. As NBC News reported this week, the United States has evacuated only about 3 percent of Afghans who worked for the American government and applied for special visas. As a result, an estimated 78,000 Special Immigrant Visa applicants are still in the country. I found that as of November, there were just 225 Afghan nationals in removal proceedings.

Europe Activates New Type of Protection for Ukrainians—Asylum Not Needed

On the same day that the Biden administration approved TPS for Ukrainians, European countries activated the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) for the first time since it became law in 2001.

temporary protection is an exceptional measure to provide immediate and temporary protection to displaced persons from non-EU countries and those unable to return to their country of origin. It applies when there is a risk that the standard asylum system is struggling to cope with demand stemming from a mass influx risking a negative impact on the processing of claims.

One of the justifications for TPD is described as follows:

“Cases of mass influx of displaced persons who cannot return to their country of origin have become more substantial in Europe in recent years. In these cases it may be necessary to set up exceptional schemes to offer them immediate temporary protection.” (available here)

Although I probably shouldn’t make comparisons until I fully understand the nuances of this new law, it does seem on the surface that TPD is very much like TPS and maybe they were modeled after each other in some way.

The benefit to Ukrainians is that they will not have to go through the typical complications and delays of the refugee or asylum processes, and will be granted authorization to remain in European countries that invoke this law for about three years. This is a very positive and, to me, surprising development since I was not aware of this law. It certainly avoids the massive bureaucratic headaches that would come with screening now one million people for asylum.

However, the invocation of TPD illustrates the way that exceptional sets of laws apply to Europeans while non-Europeans do not have access to these measures. The geographer Tim Cresswell uses the phrase “hierarchies of mobility” to put these various geographic and identity-based regimes into perspective: the types of legal and legalized forms of mobility that are available to you depend very much on who you are and where you were born. As I discuss more below, the differential access to TPD is just one example in a series of significant observations about how hierarchies of mobility are shaped by race and other factors.

Racism and the Fog of War

As I mentioned earlier in the week, race and nationality do not cease to be important in times of war or during refugee emergencies. Thankfully, the media (at least the media I read/watch/hear) have done a fair job covering the unequal treatment of people of color inside Ukraine.

I just want to highlight a few voices here. First, this quote from an African student living in Ukraine illustrates the added racial barriers to leaving Ukraine:

"We went to the border of Ukraine and Poland, but we African foreigners had problems crossing,” says Jean-Jacques Kabea, a Congolese pharmacy student living in the Ukrainian city of Lviv. (Reported by EuroNews.)

Second, if you learn anyone’s name this week, let it be Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon. Kimberly is a PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania Department of History who's studying race in Ukraine and Russia. Kimberly has been a voice of expertise and reason on issues of race in Ukraine. You can follow her on Twitter and listen to her illuminating interview on the Takeaway here.

At the same time that people of color in Ukraine are running into issues leaving the country, people outside of Ukraine looking in on the war are contrasting the positive reception that Ukrainians have received in Europe compared to how they have been treated. This quote from a Syrian refugee in an article really stuck out to me today:

“We are wondering, why were Ukrainians welcome in all countries while we, Syrian refugees, are still in tents and remain under the snow, facing death, and no one is looking to us?”, a Syrian refugee told Reuters.

The role of race and racism is definitely not subtle and not just perception. Just read what the Bulgarian President said about the Ukrainian refugees, and think about the contrast that he is making with “the refugees he is used to”.

"These are not the refugees we are used to," Bulgarian President Rumen Radev said last week about Ukrainian refugees, quoted by the Associated Press. "These people are Europeans. These people are intelligent, they are educated people." (Reported by InfoMigrants.)

Update for Online Version: An alliance of prominent civil rights lawyers from around the world on Wednesday announced it will file an appeal to the United Nations on behalf of Black refugees facing discrimination while trying to flee Ukraine. (More information here.)

Attempts to Convert Rather than Combat Russian Soldiers

There is widespread consensus that the war in Ukraine belongs entirely to the person and personality of Russian president Vladimir Putin. As a result, the current wave of Russian soldiers inside Ukraine has been treated, shall we say, more gently and gracefully than you might expect under these conditions.

Reports continue to emerge that the soldiers are all very young and inexperienced. These soldiers seem to be mostly conscripted, not a voluntary force. And many also seem to have been under the impression that military exercises near the Ukrainian border were drills, not stagings for a full-scale assault on a sovereign nation.

The Daily Podcast this morning reported that some soldiers are walking away from combat, turning themselves in to the Ukrainian military, and even sabotaging their own vehicles by puncturing and draining their gas tanks, for example. Once captured, Ukrainian soldiers have allowed their captives to call their families and provided hot food. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy has called on Russian soldiers to help end the war by refusing to fight.

This is all a mix of humanity and very good politics. Given the massive asymmetry of military force, appealing to the Russian people is a good strategy. Will this strategy pan out if and when more experienced, dedicated soldiers get involved in the fighting? The war doesn’t seem anywhere close to being over, so it’s too early to say.

Nonetheless, providing a way out for Russian soldiers on the ground isn’t just something that Ukrainians are thinking about. Tom Dannenbaum, a professor at Tufts University, argues in the Just Security blog that countries can and should recognize Russian military deserters as refugees. I won’t recapitulate the entire argument, but I want to quote directly from his article to substantiate his core argument:

As articulated in the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status, this includes those who face punishment for desertion or draft-evasion when “the type of military action” in which they refuse to participate “is condemned by the international community as contrary to basic rules of human conduct.”

Given the coordinated, international opposition to the war in Ukraine, it seems relatively uncontroversial that Russian soldiers would qualify according to Dannenbaum’s reading. It’s doubtful that Russian defectors are going to be able to simply walk off the battlefield and into Western Europe easily, but it’s possible that we could see a more concerted effort in Ukraine and neighboring countries to appeal to Russian soldiers and provide a way out of the conflict using something like refugee status as an incentive.

Tech Enters the War

Russia’s aggressive hacking industry is no secret, but what has been remarkable is both the number of malware attacks we’ve seen already as well as the level of participation in defensive technological measures and cyber warfare from civil society.

For instance, a new malware program called SunSeed, whose developer appears to be in Belarus, is currently targeting European officials involved in helping Ukrainian refugees. Another novel piece of malware called FoxBlade emerged this week, targeting Ukraine’s governmental and financial institutions. But Microsoft’s Threat Intelligence Center identified this malware early and patched their virus detention software in under three hours.

The hacktivist group Anonymous announced last week that they were taking on Russia directly through cyber warfare. The group has claimed responsibility so far for hacking Russian satellites, knocking out Russian government websites (though temporarily), and releasing government documents that claim to be linked to military plans.

But wait, there’s more. “Open-source intelligence” activists that use publicly-available information to develop actionable intel have been tracking Russian troop movements, geolocating missiles strikes, and assembling datasets that are valuable for reconstructing the timeline of the war down to the minute. It’s the Forensic Architectures methodology on steroids and crowdsourced to thousands of people.

If there are human rights trials or charges against Putin or others in the Russian government for war crimes (I remain skeptical, but let’s consider it), the granularity of this collective data will be extremely valuable. Even regardless of any official court proceedings, this could be the most documented war in human history.

THANK YOU FOR READING! 🙏🏼

If you found this information useful, help more people see it by clicking the ☼LIKE☼ ☼SHARE☼ button below. If you want to get this newsletter in your inbox, please subscribe.