We are witnessing a profound shift in the geographic forms of migrant surveillance and control, a shift that is simultaneously about migrants and not about migrants, a shift that is wrapped in the paper of liberal humanitarianism but which has its roots in new theories of social threat, the commodification and brokerage of personal data, and the operationalization of Big Data for controversial new forms of policing.

I am talking, of course, about the massive growth in the past year of the number of migrants enrolled in Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s ‘alternatives to detention’ (ATD) program. According to data released by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) last week, 182,607 people are currently enrolled on ATD, up from less than 90,000 when Biden took office.

What are ‘alternatives to detention’?

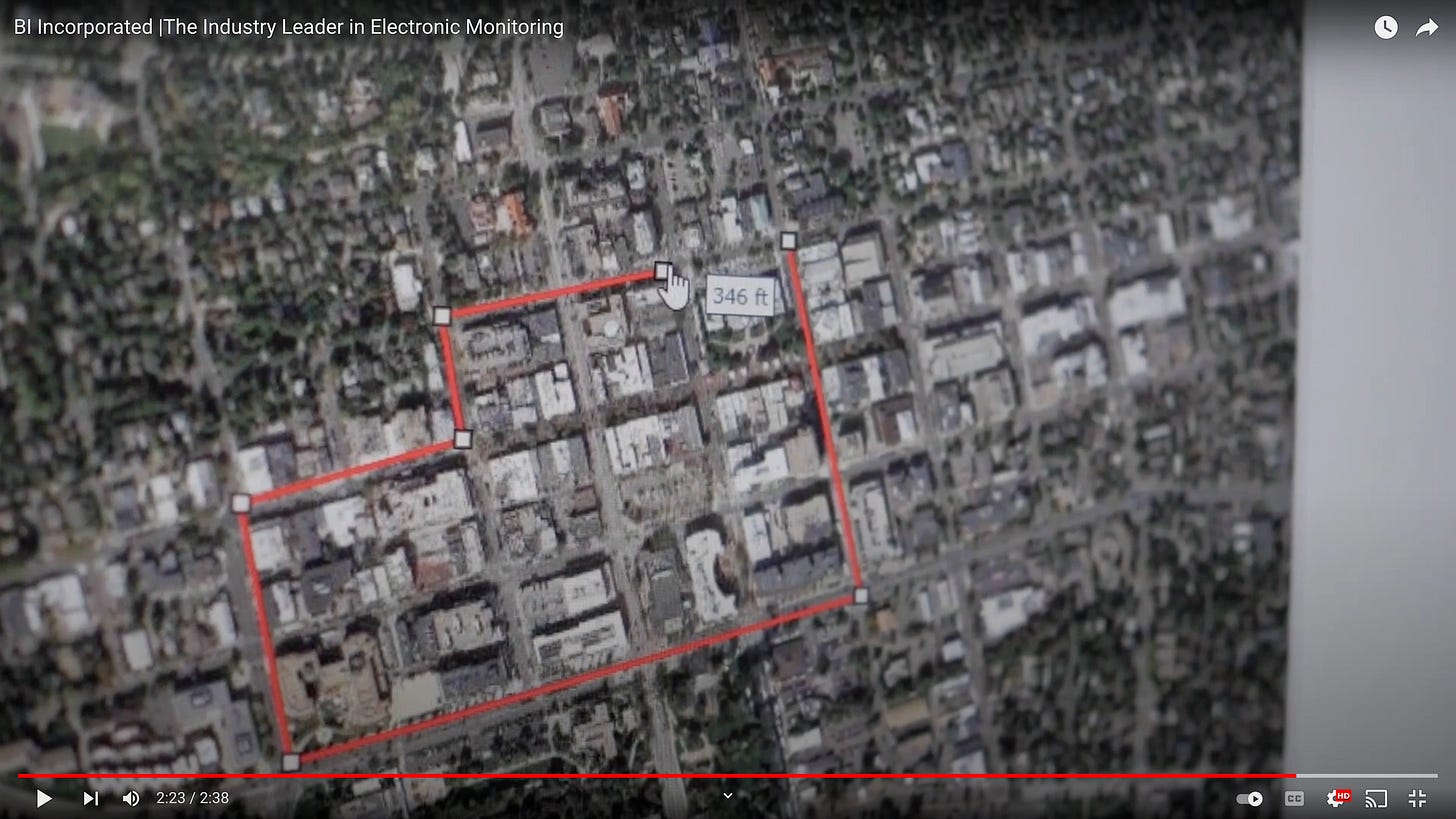

To start with, they are not alternatives to detention. ATD represents the geographic extension of carceral logic into the everyday lives of people outside of prison/detention walls, which manifests itself in new forms of digital walls around home and work, and new temporal borders around specific times and dates.

In my recent conversation with Stephen Robbins for Redirect Podcast, Stephen aptly called ATD “in addition to detention” detention rather than “alternatives to detention.” James Kilgore similarly describes these technologies as “non-alternative alternatives.”

None of this is breaking news. ICE acknowledges as much on its website when it says that ATD is “not a substitute for detention”, but rather a way for the agency to “exercise increased supervision over a portion of those who are not detained”. (We’ll come to how ICE co-opted this language in a later post.)

These walls and borders—these forms of “increased supervision”—operate at a technological level through telephonic reporting, GPS ankle shackles, and increasingly through smartphone-based applications such as SmartLINK that are less visible than an ankle-strapped device but offer even more intensive monitoring and data collection.

In fact, all of the numerical growth of ATD over the past year has been due to SmartLINK; the number of people on GPS monitors and telephonic reporting has remained entirely stagnant at around 30,000 each. SmartLINK grew from 6,000 enrollees to nearly 120,000 in less than two-and-a-half years. (Note that immigrant detention centers have hardly disappeared in the meantime and total detention numbers remain consistent.)

This growth is unlikely to stop any time soon. Stef Kight at Axios has reported that ICE could be preparing for 400,000 migrants enrolled on SmartLINK in the near future.

Consider this: there are currently over 1.6 million people facing deportation in the immigration court system alone. I see no reason why ICE hasn’t already set a goal for itself to put every single one of those people on ATD technology of some kind.

This statistical growth, however, tells us very little about the larger political and economic forcing driving these changes, tells us little about the implications for migrants enrolled in ATD, and tells us little about how these forms of surveillance and monitoring technologies are already blurring the distinction between what is and is not policing.

Moreover, unlike, say, Trump’s family separation program or the Muslim Ban, the growth of alternatives to detention is not articulated as a “get tough on border enforcement” strategy, nor has it generated sympathetic mass protests and Facebook profile banners. Rather, ATD programs come dressed in technological progressivism that serves to effectively blunt criticism and critical inquiry. I mean, seriously: who could protest something as benign as a smartphone app when the alternative is indefinite detention?

Already we can see how powerful and limiting the myopic framework of the detention/non-detention binary is.

So instead, I want to take the following series of posts to zoom and pan across the various technological, legal, political, economic, and racial entanglements of ICE’s current expansion of its ATD program in order to hopefully spark a wider conversation not just about the digitization of US immigration enforcement, but about the future of law, data, and justice.

In doing so, I will be drawing eclectically on academic research, recent reports, empirical data, first-hand narratives, and philosophy among other sources to explore these questions in a format that is hopefully readable and informative. Please join me on this rather experimental journey, and chime in regardless of whether you have a supporting or contradicting viewpoint to offer.

THANK YOU FOR READING! 🙏🏼

If you found this information useful, help more people see it by clicking the ☼LIKE☼ ☼SHARE☼ button below. If you want to get this newsletter in your inbox, please subscribe.

Thanks for this, Austin! It definitely clarifies what I had hoped, as an eternal optimist, would be humane progress in our monstrous immigration system...

Thank you for this very important information, Austin.