Will CBP One Survive Escalating Court Battles?

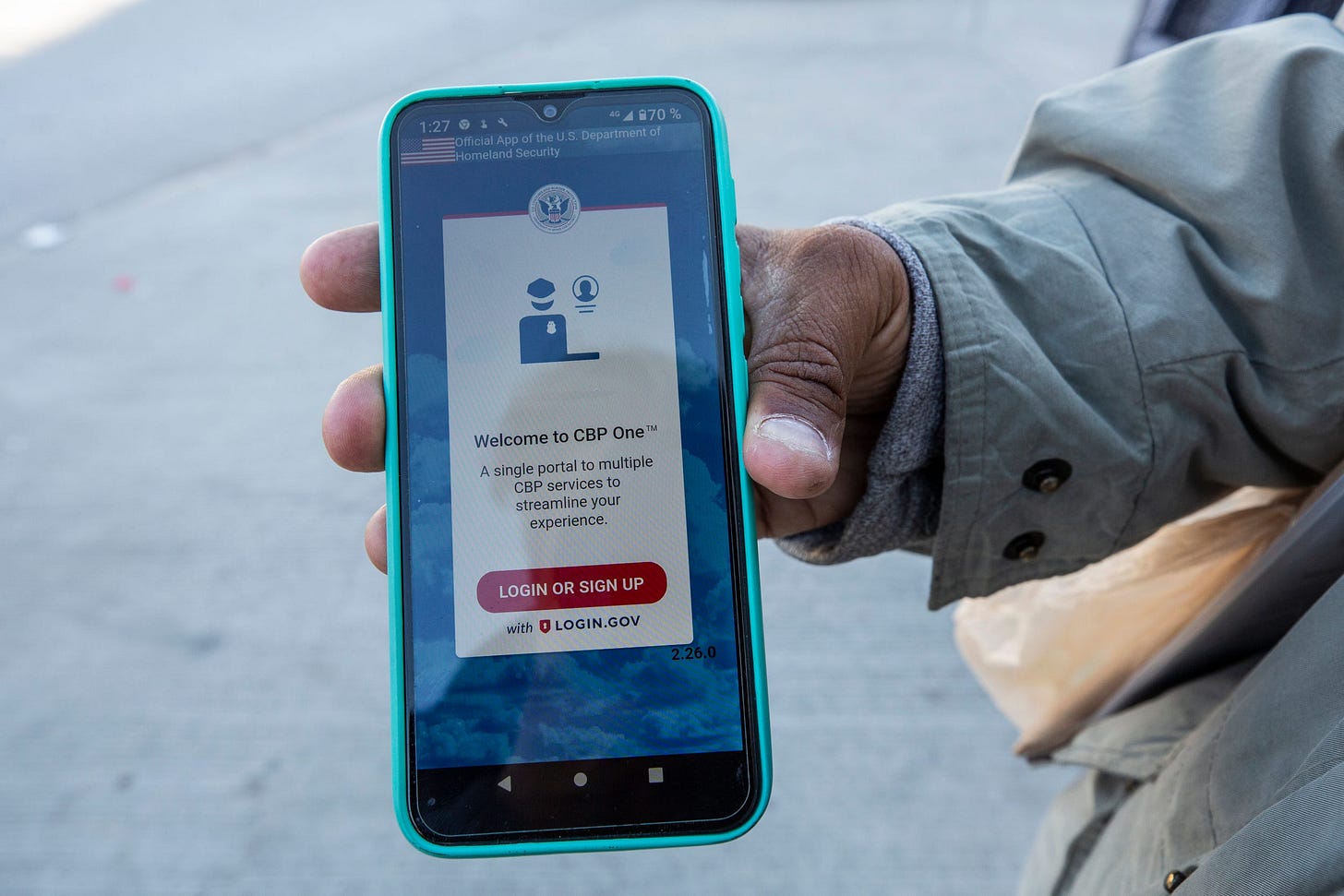

CBP's smartphone app, used mainly to manage asylum seekers, faces even stronger challenges in a new lawsuit. What if the agency had built a better app?

CBP One suffered strong criticism from a federal judge this week and now faces yet another even more pointed lawsuit challenging the app’s role in asylum management at the U.S.-Mexico border. In both cases, CBP One’s many failings, as well as the app’s role within the Biden administration’s new asylum policy. In this post, I explore two questions about CBP One now that it is becoming the topic of growing litigation.

Why is CBP One in court?

What if CBP One worked better from the beginning?

As my longer-term readers know, I’ve been tracking CBP One’s development over the past eight months. But I’ve noticed an uptick in readers over the past month, so if you’re new here and want to catch up on related posts, visit my collection of CBP One articles here. And if find this post valuable, consider leaving a like, a comment, and maybe even subscribing.

Why is CBP One in court?

CBP One is featured prominently in two lawsuits right now.

The first lawsuit is a case that dealt a major blow to the Biden administration’s new asylum policy known as the Circumvention of Legal Pathways (CLP), which was implemented in May. That lawsuit, which actually began during the Trump administration, challenged the legality of the two pillars of the CLP: (1) the restriction on accessing asylum between ports of entry or at ports of entry without a CBP One appointment and (2) the transit ban, which restricted access to asylum if migrants didn’t request asylum in a transit country first.

Last week, Judge Tigar found the policy unlawful and gave the administration 14 days to roll it back. I wrote about this last week when the policy came out (click here to read that). And here’s a PDF from the National Immigrant Justice Center explaining the judge’s decision (shout out to Azadeh Erfani).

In that lawsuit, the judge found that CBP’s reliance on CBP One was unlawful because it did not provide adequate access for migrants near the border. And the judge said that even though CBP does provide an exception for migrants that can’t use CBP One (for whatever reason), the exception is simply too limited and, besides, none of this is how Congress said asylum was supposed to work.

The judge may have also found the use of CBP One to be unlawful even if the app worked, it’s hard to say. But it’s clear that the app’s problems certainly drew the judge’s concern and undermined the government’s policy.

The second lawsuit was filed just days ago on behalf of Al Otro Lado and Haitian Bridge, two organizations that work directly with asylum seekers and other migrants. Whereas in the first lawsuit, CBP One was only part of the story, the AOL (Al Otro Lado) lawsuit is entirely focused on CBP One.

The crux of the AOL lawsuit is that CBP One contradicts a wide range of well-established laws, policies, and legal principles. I was delayed flying out of Toronto on Friday and spent 24 hours straight in that non-space of airports and airplanes, so I had time to read the complaint in detail. I learned so much that I didn’t know before about the various classes of ports of entry, the “Accardi doctrine”, and some of the finer details of non-refoulment in the US-Mexico border area that I had not understood before.

The complaint also does a great job of explicating how CBP One works, how it doesn’t work, and why. … Almost as good as my recent peer-review article on CBP One available here without a paywall.

Even more important were the first-hand accounts of migrants as part of the class-action lawsuit who were negatively impacted by CBP One. For instance, there’s Luisa who was targeted in Mexico for her cooperation with local authorities and was turned back from seeking asylum at a port of entry. Another woman missed her CBP One appointment because she was kidnapped, but when she showed up later, CBP turned her away.

These are the kinds of details that, as a mixed-methods social scientist, I really appreciate because it helps to bring the issues alive for me in a way that those of us who aren’t on the ground don’t always get to see. I don’t know all of the authors who worked on the complaint but my hat is off to them for writing so clearly that even a non-lawyer like me could understand it and be moved by it.

So that’s what going on with CBP One right now.

What if CBP One worked better from the beginning?

I can’t help but wonder if things would have been different if CBP One actually worked effectively from the beginning instead of CBP basically trying to build the plane while they flew it for the first time. Despite my skepticism about the broader implications of technology for migration control, at a practical level, I can appreciate the need to find effective ways to manage the asylum process and I think technology can play a valuable role–so long as it doesn’t actually break the law.

Suppose, for instance, that CBP One worked more effectively in January and suppose that CBP relied on the incentives that come with port-of-entry processing rather than relying so heavily on possibly illegal restrictions to asylum between ports of entry. I can imagine a version of this which, although it might not satisfy critical research types like myself, might have better insulated the agency from legal consequences and still achieved its objectives.

Instead, even though CBP One has been significantly improved in recent months, the agency is still, I think, dealing with the damage done in the early months both to real people and also to the reputation of the app. And that, to me, was part of what I was trying to get at in my recent article. These political and legal issues were created, in part, not just because of policy but because of software–and we cannot divorce the two.

Software is political.

If we understand this, we might think more critically about if and when and how we roll out software like CBP One that could have life-and-death consequences for migrants and which could also lead to a flurry of costly lawsuits. Could a better-designed app have saved lives, saved on costly litigation, and improved the asylum system?

These are strange questions to ask, but here we are. This is the world we live in now. Technology is a powerful mediating factor in the everyday lives of migrants, and rather than running from the questions or wishing technology didn’t exist, we have to get better about asking–and answering–these tough questions.

What do you think about the role of technology within the asylum system, especially CBP One? Chime in below. And thanks for reading.

Support public scholarship.

Thank you for reading. If you would like to support public scholarship and receive this newsletter in your inbox, click below to subscribe for free. And if you find this information useful, consider sharing it online or with friends and colleagues.

Your point about effective technology reminds me of the flawed rollout of the Affordable Care Act. A better design makes a difference! In the current case, it would cut the number of true horror stories.

I agree that the CBP One app should have been tested and improved before it was released into the wild, but the fact still remains that it doesn't follow our current asylum law. It discriminates against the poor who don't have access to smartphones, discriminates against the illiterate in English, Spanish or whatever languages it's currently available in. And asking for asylum as defined by the United Nations and our own INA says nothing about it can only be requested at certain ports of entry. A person is free to request asylum no matter how they reached the US or where they entered. Those issues are more worrisome than perfecting the app, IMO.