Does U.S. Immigration Policy Contribute to Organized Crime in Mexico?

A new report by InSight Crime finds links links between restrictive U.S. border policies and the growth of a multi-billion-dollar smuggling economy in Mexico.

A new report released this week by InSight Crime1, which studies organized crime in the Americas, argues that restrictive border policies since the 1990s have contributed to the growth of organized crime in Mexico and exacerbated security risks for migrants in the region.

InSight Crime’s publication gives us an opportunity to discuss the enormous multi-billion-dollar-a-year industry of migrant smuggling for the first time since I started this newsletter.

Smuggling is a frequently-invoked lightning rod in politicized discussions about migration enforcement and human rights. Often missing from these debates, however, is an acknowledgment of the relationship between U.S. immigration and border policy and the growth of human smuggling.

InSight Crime’s new report presents what I consider to be a coherent and readable introduction to this topic. So let’s talk about it.

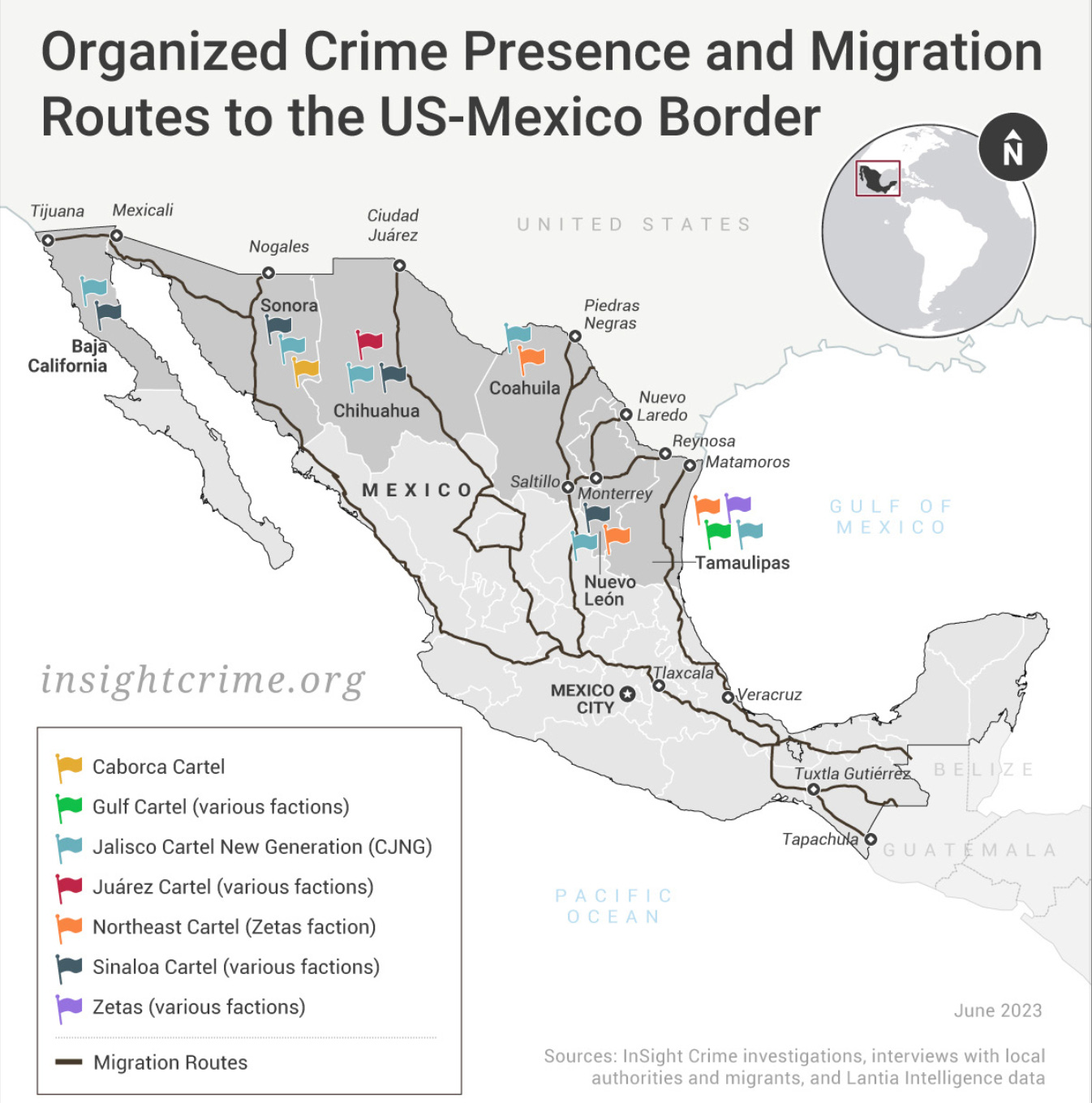

As the report states, human smuggling has replaced the smuggling of guns and drugs in northern Mexico to become “one of the most lucrative industries for crime groups” and exacerbated migrants’ exposure to extortion and kidnapping. But the origins of this transformation are not only rooted in economic and political factors in Mexico. U.S. policy plays a role here, too.

As the article explains, the US government’s prevention through deterrence policies have made human smuggling more profitable. Pedro Rios of the American Friends Service Committee once described prevention through deterrence policy as "saturating urban border communities with agents, building physical barriers and increasing interior checkpoints — ensured that migrants would be forced to seek out dangerous crossing methods, thereby increasing the likelihood of injury and death.” In short, make migrating so difficult that migrants will turn back or suffer.

Over the past three decades, migrants have not turned back. But they have suffered.

Deterrence policies, Insight Crime’s report goes on to explain, have given criminal groups more chances to exploit migrants. Specifically, they have created a bottleneck at the US-Mexico border, where migrants heading north gather to decide if they can seek asylum or find alternative ways to enter the country. As a result, these migrants are easily targeted for extortion and kidnapping.

Definition #1: “Deterrence” is borrowed from the fields of criminology and sociology, where the concept refers to programs to shape human behavior. Deterrence typically comes in two forms: general deterrence, which creates a disincentive for an entire group of people, and specific deterrence, which creates a disincentive for an individual. As you think about border policies in this article, consider whether each policy contributes to general deterrence, specific deterrence, neither, or both.

Definition #2: “Human smuggling” involves the provision of a service—typically, transportation or fraudulent documents—to an individual who voluntarily seeks to gain illegal entry into a foreign country. The key difference between smuggling and human trafficking is that trafficking is involuntary, although smuggling certainly can become trafficking.

Other researchers who have examined this phenomenon cite U.S. policy as a main driver, as well. “Restrictive immigration policies and long-standing immigration-deterrence strategies — which study after study shows don’t actually deter anyone from migrating — funnel child and adult migrants into clandestine routes of entry that force migrants to turn to smugglers for aid,” wrote Ivón Padilla-Rodríguez earlier this year.

Furthermore, strict immigration policies have widened the scope of these profitable criminal activities. The US government’s immigration policies and the outsourcing of immigration enforcement to countries like Mexico have increased corruption. By relying on other countries for enforcement and forcing migrants to stay there, officials in these nations have expanded their illegal operations, such as extortion, kidnapping, and human smuggling.

Now, one could quibble with the title “unintended consequences”, since internal government reports written even before the implementation of restrictive border policies showed that enforcement agencies were aware of these potential consequences. Nevertheless, the underlying point is consistent with scholarly research: border policies aimed at reducing migration have not usually achieved their stated goal, but they have contributed to a bourgeoning market of smuggling.

As U.S. policies such as the Migrant Protection Protocols and Title 42 have made border crossing even more restrictive, the cost of crossing the border has gone up. And in order to expand and preserve their market, cartels have increased their control over access to the border. George Mason professor Guadeloupe Correa Cabrera told Rolling Stone that the cartels “control the territory militarily.”

Even at migrant shelters, criminal organizations watch the shelters to make sure that no one is escaping their lucrative barely-underground economy—under the threat of kidnapping.

InSight Crime reports that the current price to be smuggled across the border is between $10,000 and $13,000, while simply accessing the border as a migrant (with no assistance in crossing) could cost as much as $2,000. This adds up to estimates of $7 billion a year or more.

InSight Crime’s report focuses on smuggling and crime in Mexico, but it would be a mistake to think that smuggling is an exclusively Mexican phenomenon. For example, Just last year a dozen U.S. Marines at Camp Pendleton were busted for picking up migrants who entered the country illegally and driving them 100 miles north into California.

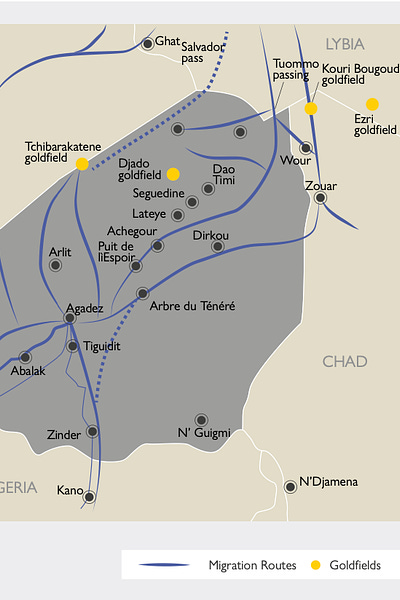

Nor has smuggling just been growing in the U.S.-Mexico border region. Europe’s increasingly restrictive border policies have also led to complex networks of smuggling throughout the Middle East and North Africa region in places where none used to exist, in places such as Agadez in Niger. See Julien Brachet’s excellent academic article or my good colleague Julia Black’s chapter on this topic available below.

In short, we can see that the relationship between border policy and smuggling is more complex and interdependent than it is often portrayed.

I want to be clear about my own position here: human smuggling is dangerous, expensive, and a lot of people get hurt. Whatever one might have thought about coyotes as guides in the past, the landscape is quite different today and we shouldn’t ignore the dangers. The fact that migrants accept these risks (some known, some unknown) is part of how we should contextualize the urgency and seriousness with which many migrants leave home and seek another life.

I also want to offer an important caveat to all this. The argument that U.S. policy is responsible for the smuggling industry in Mexico and the Americas is well-established at this point, but if it is treated as the only explanatory framework, it also risks advancing an overly simplistic explanation that ignores important changes in the local, regional, and national political economies of Latin America.

For that reason, don’t treat this as the end of the discussion, but rather as one of many foundational observations about the nature of human smuggling, particularly in the U.S.-Mexico border region, that will (I hope) prompt you to read more and ask more questions.

What do you think? If it is true that U.S. border policies contribute to the growth of the smuggling economy, does the U.S. have a responsibility to change course on policies? Should the U.S. government really be held accountable for organized crime outside of its borders? What other influential factors or policy positions have we not yet considered?

PS: Before leaving, would you mind leaving a like (🩶) below? It goes a long way to helping get this in front of new readers, and I’d appreciate it enormously. Thanks!

Support public scholarship.

Thank you for reading. If you would like to support public scholarship and receive this newsletter in your inbox, click below to subscribe for free. And if you find this information useful, consider sharing it online or with friends and colleagues. I maintain a barebones site at austinkocher.com and I share immigration data, news, and research on Mastodon (@austinkocher), Twitter (@ackocher), and Instagram (@austinkocher). You can see my scholarly work on Google Scholar.

I should mention that I have the pleasure of sharing office space with InSight Crime at the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies at American University.

Having worked on the Mexican border for over a decade, can confirm every time America does something to push Mexico, Mexico pushes back in obvious & subtle ways. It is also an axiom of International Relations that the more a country tries to control an honor-based culture, the more it triggers & empowers that culture’s artists, politicians & criminals to speak out, fight back or use the situation.

Anyone old enough, raised in a border state, & not blinded by racism or xenophobia, remembers the situation before Clinton's bipartisan IIRAIRA, when laid-off or injured workers would return to Mexico, then come back when they could work again. Coyotes were $50, cartels we're absent, & many didn't need a coyote to cross. We've given the xenophobes everything they asked. They move the goalposts every time.