Family Detention is Back: Here's What You Need to Know

Family detention ended after years of lawsuits, medical warnings, and public outrage. Now, it’s back—despite clear evidence that it’s harmful, costly, and ineffective. Get the full story below.

The U.S. government is once again detaining mothers with children inside the largest immigrant detention facility in the country in southern Texas. For years, the controversial practice known as “family detention” represented one of the most harmful, expensive, and shameful parts of the immigration enforcement system. Widespread criticism from the medical community and years of lawsuits contributed to the Biden administration’s decision in 2021 to end family detention and replace it with electronic monitoring and case management services.

Starting this month, however, the Trump administration is bringing back family detention as part of a broader expansion of immigrant detention across the country that could reach historic levels. News reports reveal that the return of family detention coincides with ICE’s renewed efforts to target immigrant families and unaccompanied minors across the country for arrest and deportation. While this is not exactly a surprise, ICE’s focus on families further contradicts the administration’s claims that it is focusing its limited resources on dangerous criminals.

When I heard that family detention would be revived, my mind immediately returned to the weeks I spent in the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas—the privately owned and operated facility that Trump is already starting to fill with immigrant families. For a generation of attorneys and researchers who came of age during the Obama era of immigration enforcement, the CARA Pro Bono Project (later the Dilley Pro Bono Project) offered us a behind-the-scenes look at family detention by inviting teams of volunteers to work for a week at a time to support detained asylum-seeking families. The facility was colloquially known as the “baby jail.” My time inside a family detention facility shaped my understanding of the political, legal, and ethical stakes in ways that profoundly influenced my research.

The announcement about family detention might easily have been diluted by the deluge of policy changes. Just 50 days into the second Trump administration, we might already find ourselves becoming overwhelmed and desensitized. When I feel this way, I find inspiration in trying to cultivate what Martin Luther King, Jr. once called in a sermon “a tough mind and a tender heart.” A tough mind is “astute and discerning,” King says, capable of lifting itself “above the morass of false propaganda” without giving in to the “bitterness” and “lack of capacity for compassion” that characterizes hardheartedness. Compassion unrestrained by a tough mind gives in to sensationalism (made easier by social media), while a tough mind uninformed by compassion becomes coldly utilitarian. To make sense of family detention requires strength and compassion.

In this context, a strong mind means a willingness to learn about how family detention works. In this newsletter, I endeavor neither to sensationalize nor desensitize, but rather to create the possibility for curiosity and dialogue based on a shared understanding of the facts. Let me assure you: family detention is worth a deep dive. Understanding the fundamental characteristics of family detention, why it is controversial, and how the past is prologue will help prepare you to make sense of renewed policy debates over family detention and enable you to anticipate how detained families are likely to be treated. To build this foundation, we need to start with the basics that you won’t get from news articles and social media posts.

While data and policy debates reveal the structural failures of family detention, the human cost is clearest in the personal stories of those detained. The treatment of families and children is a difficult and potentially emotional topic to tackle because it raises ethical questions that touch people in unpredictable ways. Even those who typically support immigrant detention often find the mistreatment of mothers and children ethically indefensible, regardless of their citizenship status. My values do not allow me to draw boundaries around my compassion based on the artificial lines of citizenship.

To understand family detention, we’ll begin with the basics: what it is, how we got here, how both Democrats and Republicans contributed to its expansion, and what is likely to happen next.

Heads up: this is one of my longest posts. If you prefer to listen to it, you can do so easily by opening this post up in the Substack app, then clicking the “play” button at the top of the screen. You’ll hear the entire post read aloud in a surprisingly realistic AI-generated voice while you drive, clean the house, or go for a walk.

Just a reminder that this newsletter is only possible because of your support. If you believe in keeping this work free and open to the public, consider becoming a paid subscriber. You can read more about the mission and focus of this newsletter and learn why, after three years, I finally decided to offer a paid option. If you already support this newsletter financially, thank you.

Family Detention is for Mothers with Children

To fully grasp why family detention is controversial, we must first clarify what it actually entails—and, just as importantly, what and whom it excludes.

The term “family detention” is a misnomer. Family detention is overwhelmingly limited to mothers with children under the age of 18 years old.1 Fathers do not typically count as ”family”, children over the age of 18 do not count as ”family“, and other close relatives do not count as “family”. Thus, the concept of “family” in family detention is artificially restrictive and, as I’ve said about the phrase “alternatives to detention”, is a bit of government euphemism that hides as much as it reveals. For this reason, I try as often as possible to use the usually more accurate phrasing “mothers with children” when describing family detention.

This is important because you are likely to see family detention described as an alternative to family separation. Yet for many immigrants, family detention actually is a form of family separation—not an alternative to it. I remember a case involving a mother who crossed the border with her young daughter and her son, barely 18 years old, who was held across the country at Stewart Detention Center in rural Georgia. A good lawyer and a favorable judge might be able to reunite these families legally, but that still meant months of painful separation.

Although the phrase family detention center is common, DHS also refers to them as family residential centers (FRCs) in the following definition.

“FRCs maintain family unity as families go through immigration proceedings or await return to their home countries. To be eligible to stay at an FRC, the family members cannot have a criminal history and must include a non-U.S. citizen child or children under the age of 18 accompanied by their non-U.S. citizen parent(s) or legal guardian(s). ICE also refers to FRCs as Family Staging Centers.”

How do families end up in family detention? Mothers with children are typically detained for one of two reasons." First, family detention centers hold families that crossed the border as asylum seekers and are now being held until they complete the first phase of seeking asylum called a “credible fear interview” (CFI). Mothers who pass this initial screening are typically released and allowed to pursue their asylum case with their children in the United States, while those who do not pass are typically deported. As far as I recall, this used to be the predominant fraction of families in detention. But with rule changes by the Biden administration and the further militarization of the border by the Trump administration, I anticipate newly arrived asylum seekers to be a smaller fraction of detained families than in the past.

The second route into a family detention center is through the deportation process. While some families are coming into the country, other families are on their way out. This includes families who were arrested and detained by ICE in the interior of the country, and are now being forcibly deported rather than being allowed to leave on their own. This will almost certainly include many families who entered the country lawfully under the Biden administration and who are now being targeted for deportation (in some cases, perhaps unlawfully). It might also include families arrested near the border and awaiting deportation because they did not pass a CFI. Due to the changes I noted above, this is likely to make up the majority of people in family detention in the coming weeks and months.

Let’s discuss two terms that you will see in writing on family detention: “family unit” and ”family group”. Federal law does not define what a family unit is, but CBP and ICE tend to define a family unit as an undocumented child under the age of 18 who is also accompanied by an undocumented parent or legal guardian. Note that the definition for family unit is more expansive than the definition of family for family detention purposes. Family group is a more expansive category that includes various other types of relatives. Who counts in a family group and how family groups are treated is largely left up to the discretion of frontline officers.

A final point in this foundational section. Family detention is for mothers and children–but what is family detention really for? DHS knows that civil immigrant detention is not allowed by law to be a form of “punishment.” Nevertheless, the agency has said many times that it uses family detention for its deterrent effect on other immigrant families. In an announcement from 2016, ICE said that “family detention facilities help ensure timely and effective removals that comply with our legal and international obligations, while deterring others from taking the dangerous journey and illegally crossing into the United States.” Judges have ruled that it is not legal to detain families as a deterrence strategy, but this underlying justification continues to animate family detention regardless.

Family Detention’s Villain Origin Story

Like every immigration policy, the question of where to begin our history of family detention is a political question as much as an historic one because it depends on how we define family detention. If we restrict our definition to the modern one, as I do below, the family detention system emerged in the 1980s at the Port Isabel Detention Center then took more lasting shape with the Berks facility that opened in 2001. But if we consider the full range of examples of family detention, we would also be forced to include Japanese internment (made possible through the Alien Enemies Act that Trump has just begun to use again), gendered forms of enslavement and containment in the U.S. South, and perhaps certain forms of indentured servitude and coercive employment that affected entire families. I will not attempt to explicate those histories here, but just remember that every backstory has a backstory.

For our purposes, I will skip over the first 20 years of intermittent family detention and begin our story in March 2001 in Pennsylvania. ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) opened the Berks Family Residential Center in Leesport, Pennsylvania in 2001 to hold immigrant families in ICE custody. In ICE’s words from 2011, the existing local facility was retro-fitted for families who were in the deportation process and subject to mandatory detention. As a reminder, certain immigrants are subject to “mandatory detention” for reasons outlined by Congress, which means that ICE is, for the most part, required to detain them as a matter of law. The recent passage of the Laken Riley Act significantly expanded the types of immigrants who are subject to mandatory detention.

I want to focus on an interesting sentence in ICE’s description of Berks. ICE say, “The Center is an effective and humane alternative to maintain the family unity as families await the outcome of immigration hearings or return to home countries.” The description reinforces my description above. However, notice the phrase “humane alternative.” Two things to note here. First, the construction of the sentence avoids finishing the thought. A human alternative to what?, you might ask. They imply family separation, but they do not come out and say it—probably because the concept of family separation, while long familiar to immigration attorneys and researchers, did not become common parlance until Trump’s family separation policy in 2018.

Second, notice that family detention was (and is) frequently described by ICE using humanitarian terms. Scholarly work on “humanitarian borders” has usefully critiqued the duplicitous appropriation of humanitarian discursive frameworks. One phrase I quite like is offered by Chouliaraki and Georgiou in The Digital Border. They refer to “humanitarian securitization” as “… a regime of border power that combines concerns of national security—protection against risky migrants—with care for those same migrants as precarious, vulnerable populations.“ The critique border scholars make (and which I fully endorse) is that while the government views these two aspects of migrants as distinct, one may just as easily recognize that migrants’ precariousness and vulnerability is not separate from the governments treatment of migrants as security threats; rather, it is the government’s own treatment of migrants as security threats which renders migrants precarious and vulnerable, and therefore “in need” of the government’s humanitarian protection. In a formula that is common far beyond the domain of immigration, the state manufactures a crisis, then purports to save the country from this crisis in ways that justify the government’s own interventions through new forms of governance.

Berks is the oldest continually operating family detention center in the country with around 100 beds—much smaller than the facilities that came after it closer to the border. While Berks opened before 9/11, the larger T Don Hutto Family Detention Center was opened after 9/11 in 2006 by a private contractor formerly known as the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) but now known as CoreCivic. Shortly after it opened, squalor inside the facility attracted a major lawsuit by the ACLU that forced the facility to improve living conditions. The Center’s reputation was not helped by the fact that a supervisor at the facility was arrested for several counts of sexual assault. Further investigations found that staff had retaliated against people who filed complaints at this for-profit facility. The facility stopped holding families in 2009. (See Margaret Talbot’s excellent essay for the New Yorker from 2008 that feels like it could have been written yesterday.)

Obama Goes All in on Family Detention

Family detention between 2001 and 2013 laid the groundwork, but 2014 is when things really start to blow up. 2014 and 2015 were intense years for immigration across North America and Europe. I would argue that these few years rather quickly and radically reshaped the relative importance of immigration in the Global North in ways that we have not yet fully appreciated. Mostly exogenous factors—ecological change, geopolitical instability, and economic crises—contributed to growing numbers of asylum seekers arriving at the borders of the EU and the US, accompanied by a diversification of the nationalities, ages, and genders of migrants. In short, families, children, and refugees were seeking protection at unprecedented levels because of global instability shaped, in no small part, by the countries that refugees ultimately fled to. While I don’t have the space here to unpack all of those factors, it is essential that we recognize that backdrop as we think about what happened next.

In 2014, border enforcement agencies reported a surge in unaccompanied children and family units arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. This was the era of widely circulated images of children confined in chain-link enclosures within overcrowded border facilities.

In response, and the Obama administration made the decision to detain recently-arrived families. But since the T. Don Hutto Residential Center stopped holding families in 2009 due to poor conditions and Berks was located thousands of miles away from the border, DHS relied on substandard temporary housing at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Artesia, New Mexico. Artesia, a genuinely triggering word that conjures up disgust and outrage among attorneys who worked there, held immigrants families from June to December 2014. Like Hutto,several lawsuits were filed over terrible living conditions at Artesia, as well as over limited access to legal representation, dismissive treatment of asylum seekers, and lack of child-specific care despite holding several hundred children and their mothers.

By the end of the 2014, the Obama administration had contracted with private prison company the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), which had just rebranded as CoreCivic in that same year, to build and operate the South Texas Family Residential Center (STFRC) in Dilley, Texas. The Dilley detention center would include 2,400 beds, making it the largest immigrant detention center in the United States—a record it holds to this day. Like Artesia and most other large immigrant detention facilities, Dilley was a small, strategically-located remote town that made it difficult for attorneys and other advocates to visit. Dilley was also conveniently located near another detention center in Pearsall, Texas, known as the South Texas ICE Processing Center, which had been run by CoreCivic’s competitor, Geo Group, since 2005.

Emily Gogolak’s outstanding article on the social landscape of Dilley, Texas, is required reading for anyone who has not been there personally. Like most rural communities with prisons or immigrant detention facilities, the government failed to deliver on promises to bring economic development to the town. Gogolak’s observations about Dilley mirror my own observations about the failure of the “prosperity gospel” of immigrant detention centers in a previous post about Lumpkin, Georgia, home to Stewart Detention Center.

At the same time that CoreCivic was opening the new facility in Dilley, the Karnes County Residential Center, which had housed male immigrants since 2012, converted its infrastructure to also enable family detention with another approximately 800 beds. Thus, by December 2014, DHS was moving already-detained families from Artesia to Karnes and Dilley and sending newly-detained families to these facilities from the border. Advocates celebrated the closure of Artesia but lamented that the administration choice to lean into family detention rather than pursue alternatives. The total family detention beds went from 90 to 3,700 in one year of the Obama administration.

Flores Settlement & Detained Children

As I have already briefly shown, the U.S. government’s treatment of detained immigrant children and families has constantly fallen short of even of its own low standards and repeatedly drawn the criticism of federal judges. No sooner did the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) (the precursor to ICE) begin detaining children in the 1980s than they were exposed for the mistreatment of children in detention. A case you might have heard of known as the Flores case began in 1985 on behalf of Jenny Lisette Flores, a Salvadoran girl held with other children in prison-like conditions with adults—including men with criminal records. They were forced to shower in front of guards and were often handcuffed during movement and transportation even though they were children. The children were not given a hearing, faced indefinite detention, and were pressured to self-deport despite being asylum seekers.

The Flores case eventually reached a settlement in the 1990s that established standards for the treatment of children in detention. The conditions of the Flores Settlement were already in tension with the growth of family detention during the Bush administration. It came to a head during the explosion of family detention during the Obama administration. Here was the issue: the Flores emerged from the detention of unaccompanied children, but did those same standards for child detention still apply when the child was with a parent? In 2015, Judge Dolly Gee said “yes”, child standards are child standards. The government doesn’t get to treat children worse just because their parents are with them. Thus, Flores was understood to apply to family detention, as well. The 2015 case also found that holding children with their families in detention for 20 days, if that was as fast as the government could screen family members for reasonable or credible fear, could be acceptable, especially if that would permit the government to keep the family unit together.2

Remember: it was the Obama administration fighting to reduce child detention standards at the time, not Bush or Trump.

CARA Project Impactful, but Family Detention is Unsalvageable

Several organizations came together in response to the due process failures of family detention in Artesia, leading to the creation of a pro bono legal representation project at the family detention center in Dilley, Texas. This effort became known as the CARA Pro Bono Project. Though I do not claim to know the full history, here are the essentials: CARA brought together Stephen Manning from Innovation Law Lab to manage the intense data needs of thousands of cases, while national organizations like Catholic Charities oversaw volunteer recruitment. Together, they mobilized attorneys, paralegals, translators, and other volunteers to provide legal support to asylum seekers. Beyond helping migrants understand the CFI process, CARA also documented numerous human rights abuses inside the detention center.

It was during this time that I became involved. The first attorney hired to run CARA was Brian Hoffman, an immigration attorney and Ohio State graduate whom I had been introduced to by Amna Akbar. Shortly after we met, Brian was tapped to lead the project, and he insisted that I join him in Texas for what he promised would be an education like no other. He was right.

During my first week volunteering, I witnessed firsthand the emotional and physical toll that family detention took on mothers and children. I observed detained court hearings, saw the rigid daily routines that kept the facility running, and met people who would go on to do incredible work in the field. Among them were Ian Philabaum, who later worked for both CARA and Innovation Law Lab; Alex Mensing, who supported asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border and became publicly recognizable during the first Trump administration; and John Washington, an author and now friend whose book The Dispossessed remains one of my top recommendations for its moral and intellectual clarity on asylum.

Many people passed through CARA during its years of operation. Some lawyers went on to work at the Department of Homeland Security while others were inspired to shift into immigration work. Some attorneys and volunteers threw themselves into the work of defending immigrant mothers and children, often at great personal cost.

Beyond professional connections, the experience was deeply personal. I saw the relief that simple procedural explanations offered mothers, who often had no idea where they were or what was happening to them. One moment that has stayed with me is Christmas Day in 2015, when I spent hours entertaining a four-year-old child while her mother met with an attorney to prepare for a Credible Fear Interview. Mothers reported that months in detention caused their children to regress to earlier stages of psychological development. Physical ailments of all sorts were treated not with specialized care but with packets of honey and Tylenol. In a facility of nearly a thousand women of child-bearing age there was not a single gynecologist.

CARA provided the real-world education that Brian had promised, but it also revealed both the potential and the constraints of a well-resourced, coordinated representation project. The case management data was clear: families with access to legal representation and administrative support had better chances of succeeding in their initial asylum interviews. Yet, despite CARA’s effectiveness, it was never enough to fundamentally change the reality of family detention. Everyone knew it. In the end, CARA’s success did not justify the existence of family detention—it proved that the system was unsalvageable. The project’s ability to mobilize resources and support asylum seekers only underscored the deep injustice of detaining families in the first place. Many concluded that family detention should never exist under any circumstances, especially under a for-profit model that seemed ripe for human rights abuses.

Detention Watch Network (DWN), a longtime critic of immigrant detention, remains one of the most vocal and steadfast opponents of family detention. The flyer below illustrates their position.

Family Detention Center Sued Over Child’s Death

CARA wasn’t the only one that found that for-profit family detention harmed children and undermined basic human rights. Reports began to flow forth from medical professionals. Chief among them was The American Academy of Pediatrics which found that family detention facilities “do not meet the basic standards for the care of children” and called “for limited exposure of any child to current Department of Homeland Security facilities.”

But perhaps the most scathing findings came from the Department of Homeland Security itself. In 2016, DHS Advisory Committee on Family Residential Centers issued a lengthy 159-page report that remains heavily cited and mostly ignored. The report strongly criticizes the practice of family detention, particularly highlighting its harmful effects on children’s mental and physical well-being. The report details significant medical and psychological concerns, including the exacerbation of trauma, increased anxiety and depression, and inadequate healthcare services within detention centers. It emphasizes that detention is never in the best interests of children, citing evidence that detained children experience developmental delays and distress due to prolonged confinement.

The report goes further to condemn family detention as an inappropriate and unnecessary practice, recommending that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) discontinue the general use of family detention except in rare, individualized cases where detention is the only option to mitigate specific risks. Instead, it advocates for community-based case management programs as a more humane and effective alternative. The report ultimately concludes that family detention is fundamentally flawed and should not continue as a practice. As the report states:

“The very experience of detention is a continuing source of trauma for families who fled to the U.S. seeking safety.”

Despite these findings, family detention continued and families held in detention continued to suffer. Anyone who visited family detention centers or read the avalanche of alarming reports about family detention after the Obama expansion in 2014 would have been justified in worrying that worst was yet to come. And that’s exactly what happened.

In early 2018, Yazmin Juárez and her daughter, Mariee, were detained at Dilley after seeking asylum in the United States. While at the family detention center detention, Mariee began to suffer congestion and cough. With minimal treatment, the child’s conditioned worsened until ICE eventually decided to release them both. (It is not unusual among cases like this for ICE to release someone after their medical conditions worsen but, strategically, before they actually die in custody.) Mariee’s condition declined until she died in a hospital in Philadelphia, suffering from a “catastrophic intrathoracic hemorrhage.” She was not yet two years old.

Yazmin Juárez filed a $60 million lawsuit shortly thereafter that exposed the same medical indifference to immigrant children that those of us who visited the facility had heard. One doctor summarized the circumstances surrounding the events of Mariee’s death as follows:

“After reviewing the medical records from Mariee’s treatment at the Dilley detention facility, it is clear that ICE medical staff failed to meet the most basic standard of care and engaged in some troubling practices such as providing pediatric care over a long period of time by non-physicians without supervision,” said Dr. Benard Dreyer, the former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics and a pediatrician at New York University Langone Health. “If signs of persistent and severe illness are present in a young child, the standard of care is to seek emergency care. ICE staff did not seek emergency care for Mariee, nor did they arrange for intravenous antibiotics when Mariee was unable to keep oral antibiotics down. These are just a few of the alarming examples of how ICE medical staff failed to provide proper medical treatment to this little girl.”

Mariee’s mother brought her to the United States because she believed her daughter would be safe. Instead, she lost her daughter to the US immigration system.

Trump Tries to Get Around Standards

Under normal circumstance, the death of Mariee Juarez and the subsequent lawsuit might have prompted further reforms to family detention. Instead, just as Juarez’s lawsuit became public in September 2018, the Trump administration was trying to circumvent the Flores settlement by issuing a new federal rule that would have allowed the government to, among other things, keep families detained indefinitely and lower standards of care for children.

The Trump administration’s contempt for mothers and children was on full display. DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen described the Flores standards of treatment for children as a “legal loophole“ that ”significantly hinder[ed] the Department’s ability to appropriately detain and promptly remove family units that have no legal basis to remain in the country.” (Nielsen resigned not long after in 2019 under pressure from the Trump administration for not being tough enough on immigration enforcement despite overseeing the family separation policy.)

An unimpressed Judge Dolly Gee recognized the new rule for what it was: an attempt by the government to weasel out of what it already agreed to and quickly blocked the rule, telling the government that it “cannot simply ignore the dictates of the consent decree merely because they no longer agree with its approach as a matter of policy.” Thankfully, the rule never went into effect. Even so, immigration officials within the Trump administration then and now–including Thomas Homan and Stephen Miller–will no doubt seek to undermine the Flores Settlement again.

Biden Suspends Family Detention

In 2021, after years of lawsuits and reports of abuse inside family detention centers, the US government finally switched tactics. The Biden administration first began to draw down how many mothers and children were held in family detention centers and reduced the length of time families were held before being released. Families were cleared out of Berks and the facility was repurposed for adult detainees only. By December, Dilley and Karnes were also repurposed for adult detainees. and for the first time in twenty years, DHS’s total family detention population reached zero.

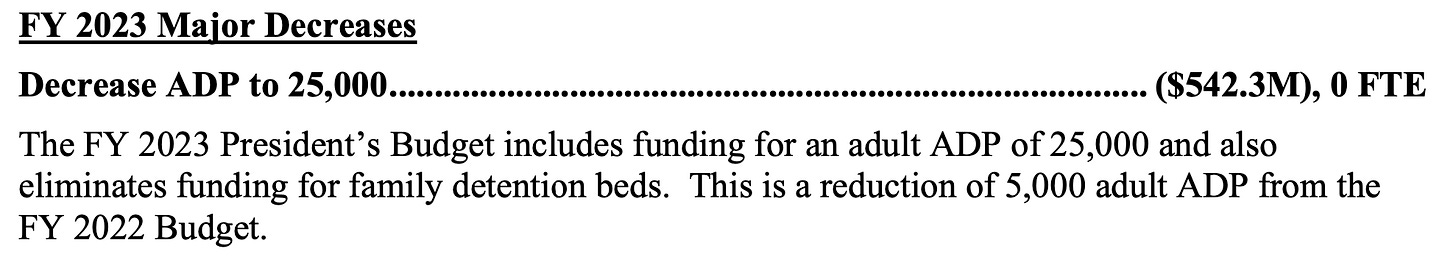

These decisions were reflected in DHS’s bottom line funding. By FY 2023, DHS had eliminated the budget for family detention altogether.

And by 2024, ICE closed the Dilley facility entirely, describing it as “the most expensive facility in the national detention network” CoreCivic revenue for the detention center in Dilley in FY 2023, when the facility only held adults, was $156.6 million.

It’s important to remember that part of what made the end of family detention possible was not the moral superiority of the Biden administration–but rather, the administration’s decision to leave the pandemic-era policy known as Title 42 in place. This policy turned away all migrants at the border, including asylum seekers, which then reduced the demand for family detention. Once faced with the end of Title 42 in 2023, the Biden administration seemed poised to restart family detention. Rumblings of this eventuality inspired a flood of warnings from faith groups, medical professionals, immigrant rights advocates, and the human rights community. Fortunately, the Biden administration did not restart family detention.

Although the Biden administration suspended family detention, the underlying laws and infrastructure for family detention was never fully dismantled, and the political incentives to use it—deterrence, optics, and profit—remained intact.

Family Detention Is Back, We Know What Happens Next

Given family detention’s track record, we can reasonably anticipate that the same negligent, abusive, and inhumane treatment of immigrants will continue or possibly get worse under this new era of family detention. This includes a predictable and avoidable number of deaths, including children, that my colleagues like attorney Andrew Free writes about (see his Substack newsletter #DetentionKills).

We also have no reason to conclude that DHS has given up on its longstanding efforts to avoid accountability for its treatment of of immigrant families. Watch for the agency to challenge the Flores settlement again during the second Trump administration. In fact, Thomas Homan has already told Sheriffs he want to reduce detention standards across the country. Jack Herrera just wrote about this in an article for The Atlantic, in which he correctly observes that a projected spike in immigrant detention is likely to lead to even more deaths in detention while a corresponding lack of systemic accountability means we, the public, might never find out about these deaths.

Just as the consequences of family detention are clear and foreseeable, so are the official responses of Trump’s appointees. Recall the family separation policy of the first Trump administration, a policy that the public and even many Republicans at the time viewed as a bridge too far. Caitlin Dickerson’s authoritative article on family separation exposes the feigned ignorance of immigration officials at the time and the ongoing damage caused by this feigned ignorance for years to come.

“Many of these officials now insist that there had been no way to foresee all that would go wrong. But this is not true. The policy’s worst outcomes were all anticipated, and repeated internal and external warnings were ignored. … A flagrant failure to prepare meant that courts, detention centers, and children’s shelters became dangerously overwhelmed; that parents and children were lost to each other, sometimes many states apart; that four years later, some families are still separated—and that even many of those who have been reunited have suffered irreparable harm.”

Family detention is no different. Trump administration officials cannot plead ignorance about the foreseeable consequences. We should not tolerate immigration officials’ attempts to feign ignorance once again or to evade moral responsibility for what is about to happen to mothers and children who are going to suffer enough as a result of family detention.

What do you think?

Share your perspective on family detention using the following poll, then join the conversation in the comments.

Many of my readers know a lot about family detention. Please feel free to add context I missed or point out facts you feel I got wrong in the comments below.

Consider Supporting Public Scholarship

Thank you for reading. Please subscribe to receive this newsletter in your inbox and share it online or with friends and colleagues. If you believe in this work, consider supporting it through a paid subscription. Learn more about the mission and the person behind this newsletter.

The first version of this post said that family detention was strictly limited to mothers with children. This was not accurate. I do not recall ever seeing or reading about fathers with children in family detention. But as my colleague Pauline White Meeusen pointed out to me, there are cases (albeit rare) of fathers held with children in family detention. However, examples of fathers in detention from the Guardian and the Texas Tribune involve fathers being separated from their children for much of their time in detention, thus illustrating the underlying point that even though fathers are not legally precluded from family detention, as a matter of practice, fathers do not typically count as a part of family detention in the same way that mothers do. Big thanks to Pauline for setting me straight on that.

The original version of this article was written in a way that made it seem that the 1997 settlement resulted in a 20 day hard limit on how long ICE could detain children. This was not accurate on two accounts. First, the 20 day timeframe is not a strict limit but a strong suggestion based on DHS’s claim in court that it could make most CFI decisions in 20 days. More generally, DHS argued that it should be allowed to detain families until a CFI determination could be made. Second, although I knew that the 20 day timeframe was a key part of the Flores case in some way, I was mistaken to attribute it so directly to the original 1997 settlement; it emerged from a motion to enforce within Flores in 2015. My thanks to Melissa Adamson from the National Center for Youth Law for reaching out to me directly to help me understand these substantive issues.

I once worked on a case during the Biden admin where the mother was separated from her 16 year old daughter in Colombia on their way up to the border. The daughter miraculously made it to the border and was in ORR waiting for her mother to find her. After maybe 6 months she was just about to be placed in foster care when I became aware of the case and the mother and her other 3 children. Even after identifying her daughter in a detention center in TX, it took another 4 months for them to be reunited because of all the bureaucratic steps in between. I'm sure there were and are shortages of social workers, but this case cemented in my mind the blasé approach the admin had to reuniting families. I'm sure this young woman will be forever traumatized. The cruelty is the point.

Family detention always leaves me speechless... with disgust, with fear, with hatred of the US, with sheer horror of what all we put these families (particularly the children) through who only want to immigrate to a safe place. Thanks for such a thorough look at this topic.