A new infographic posted on social media by Families of New York makes a series of false, incomplete, or just plain incomprehensible claims about asylum seekers. Let’s take a closer look at the growing problem of immigration misinformation, understand what this infographic gets wrong, and set the record straight.

Sections in today’s article:

Immigration Misinformation & Brandolini’s Law

Misinformation and Misinfographics

Immigration Misinfographic Case Study

Misinformation, Disinformation, or Just Sloppy?

1. Immigration Misinformation & Brandolini’s Law

Anyone who has worked in the immigration space for at least a few years has seen the rampant growth of misleading information about immigration as well as the corrosive effects it has on public discourse. Untrue or decontextualized information about immigration undermines our ability to have an informed debate about facts and policy because our energy is consumed with false information instead. Immigrant themselves can be the targets of misinformation.

Misinformation can also be dangerous. Conspiratorial misinformation about migrants has also shown up in social media posts of domestic terrorists like the attacker at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh or the manifesto of the Walmart shooter in El Paso.

I think one reason that immigration lends itself to misinformation is because immigration is so often treated as a numbers problem rather than as an essential feature of human societies. Numeric metaphors pervade anti-immigrant discourse from the very early days of the anti-immigrant movement, such as Lothrop Stoddard’s white supremacist treatise “The Rising Tide of Color", to today’s recycled primetime B-roll of large numbers of migrants arriving in Europe or North America. Another reason is that so few people (including, unfortunately, some of the loudest personalities) really understand the immigration system and so may not be the most reliable interpreters of the available immigration data.

I have been informally tracking examples of immigration misinformation for the past two years or so, noting when immigration data is misused, insufficiently contextualized, or flat-out wrong. I don’t spend much energy calling out misinformation (except for some egregious examples).

First of all, that’s not my job (fun as it is from time to time), and I prefer to focus on my best work rather than my busiest work. Second, and more importantly, there would be no end to the work. Brandolini’s Law (also known as the bullshit asymmetry principle) states that the amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude larger than is needed to produce it. Basically: it’s always easier to lie than to go to the effort of correcting other people’s lies. Nowhere is this more true than in the immigration world.

However, sometimes pointing out a particularly convoluted, effective, or widespread example of misinformation can be a useful exercise for understanding how to spot misinformation and for learning more about the immigration system in general. Let’s do that today.

2. Misinformation and Misinfographics

Let’s start with a classic distinction between misinformation and disinformation. Misinformation is false or misleading information that is spread unknowingly. People think it’s true, but it’s not. Disinformation is false or misleading information that is spread knowingly. People know it’s untrue, but they spread it anyway. (This is going to be relevant, I promise. Also, there’s a quiz at the end.)

The distinction between misinformation and disinformation is a fuzzy one, to be sure, especially since motivated reasoning, or the eagerness to believe information that supports already-held beliefs, plays an influential role in what people believe to be true.

For example, the recent lawsuit by Dominion Voting against Fox News for broadcasting false information showed that Fox News knowingly spread debunked or facially absurd conspiracy theories. That’s disinformation. Your uncle1 on Facebook who has been posting “lock her up!” memes for the past five years may have been all too willing to believe that Biden won the election because Hugo Chavez planted votes for Democrats in the Arizona voting machines (or whatever, I can’t keep up with the theories). Your uncle’s posts, absurd as it sounds, are more likely to be misinformation, since he may really believe what he’s seeing on Fox ‘n Friends.

Much of what we encounter as dis- and misinformation is narrative, but a lot of false information also presents itself as data. Or more precisely, data is often woven into visual and verbal narratives in order to imitate the rhetorical form that truth statements take, even when false narratives are known to be false. This can happen in verbal and written narratives where speakers (or writers) will use statements like, “research has proven…” or “researchers say…” followed by some statistical measure that sounds convincing. Be skeptical of these kinds of statements. Researchers have shown that 93% of these types of statements turn out to be false.2

An increasingly common way for inaccurate or misleading data to be spread is through visual representations—especially wrong infographics or what are also known as misinfographics. Misinfographics use the authoritative presentation style of infographics to convey false or misleading information and may be uniquely convincing on social media platforms where visual information is prized.

In the process of writing this post, I realized that what interests me about misinfographics isn’t just that they can be misleading, but that they can be misleading in so many ways. To put it in a more scholarly register and give it a name, let’s say that misinfographics can be uniquely worrisome because of their ability to manifest high rates of misinformation density. And let’s say that misinformation density is some kind of formula that combines both the form and content of misinformation into a finite space.

If, for instance, you wanted to tweet (text only) as much misinformation as possible, you would only have 260 characters (or whatever limit you get if you pay for Twitter Blue, but virtually no one pays for that). That’s one form (text) and whatever you can squeeze into the character limit. If you also tweeted a misleading photograph with your tweet, that would expand the misinformation density of that tweet by adding a second form (visual: photo), plus whatever content is in that photograph.

Infographics can be powerful because they have high information density, typically a combination of data points, graphs, descriptive and interpretive statements, references, etc. High rates of information density also mean high rates of misinformation density.

If we combine this observation with the prior discussion, we can begin to see that misinfographics are particularly challenging to make sense of because they might combine misinformation and disinformation together at the same time. And if we take Brandolini’s Law into account, we can also begin to see that unpacking a single misinfographic takes much more work than a simple false statement that contains at most one or two inaccurate claims.

In short, be skeptical of infographics! It has become easier than ever to create infographics using online tools, which means it has also been easier than ever for people who don’t know what they’re doing (or don’t care about presenting an accurate picture of the facts) to pump out mis/disinformation. Often a simple, well-constructed graphic is much more effective than trying to jam a bunch of data points together.

3. Immigration Misinfographic Case Study

Families for New York (FNY) posted this misleading tweet and infographic below on August 25, 2023.3 It contains several points of factual errors, improperly contextualized data, and uncited (or wrongly cited) claims. Talk about misinformation density!

Before we can get to the misinfographic itself, we should start with the text of the tweet, line 1: “We believe in facts and healthy debate.” Great opening, I couldn’t agree more. The real question is whether anything that follows this sentence is capable of demonstrating or reinforcing this purported commitment to facts.

Line two is a two-parter. First, it appears that FNY received some data directly from the local CBP office in New York City about migrants who are arriving in New York. It’s not unusual for the agency to respond to either FOIA requests or press requests, so this doesn’t represent a problem in itself. The question I have is how exactly CBP is calculating this since it’s not as if CBP is transporting migrants around the country. It’s possible that CBP is providing data based on the city that migrants tell CBP they plan to move to, but I tend to think of ICE, not CBP, as having the more reliable data on migrants’ location since it is ICE that will effectively be responsible for migrants away from the border.

Either way, I am generally skeptical about simplistic top-level numbers like these since we have no information about how these numbers were produced. It seems that FNY also has questions about the reliability of these data since they say that the data “raises questions and has gaps”. Note that they do not, however, say what those questions and gaps are, nor does it appear to prevent them from drawing sweeping conclusions.

This is a common feature of misinformation that I call an insincere qualification. An insincere qualification is a qualification that appears to give the speaker an air of objectivity and authentic curiosity, but the qualification itself actually undermines the forthcoming claims. For example, among election deniers it goes something like this: “I don’t understand everything about the whole election process, but I do know that there are just too many inconsistencies for it to be a fair election.” The qualification (i.e, not understanding how elections work) undermines the claims that there are “too many inconsistencies”, since anyone who understands how elections actually work also understands the difference between routine human error and conspiratorial efforts to undermine an election.

An insincere qualification is precisely what we see here, since FYN goes on to claim that the vast majority of migrants coming to NYC would not qualify for asylum—quite a bold claim based on data that FYN claims is faulty.

Relatedly, the keyword here is “qualify” (i.e., qualify for asylum), which is a confusing choice in this context. If we take the term “qualify” to mean its closest synonym “eligible”, this is not accurate. There is a difference between being eligible for asylum and being granted asylum. Lots of people are not eligible to apply for asylum, including people with certain criminal backgrounds, people who have already been denied asylum, and people who were involved in persecuting others (among other reasons, with lots of exceptions). This is different than whether a judge chooses to grant asylum. Asylum is a discretionary matter, which means that it’s largely up to the decision of the individual judge whether to grant an asylum application. Anyone who has seen asylum hearings in court knows that judges routinely deny applications of otherwise eligible and sympathetic applicants who, in the judge’s opinion, do not rise to the standard of asylum.

On the other hand, if we take the phrase “qualify for asylum” to mean “are granted asylum”, then I suppose it is at least internally consistent with the misinfographic below the tweet. But this confusing use of language reflects a lack of real understanding about how asylum works and how to appropriately and precisely describe the process. Already there are some holes in the whole “we believe in facts and healthy debate” part, but I’m not sure if this is because FNY is trying to advance a certain view of migrants or if they are acting in good faith but just don’t really understand the system.

Let’s move on to the misinfographic. I’ll post it again here so it is clearer.

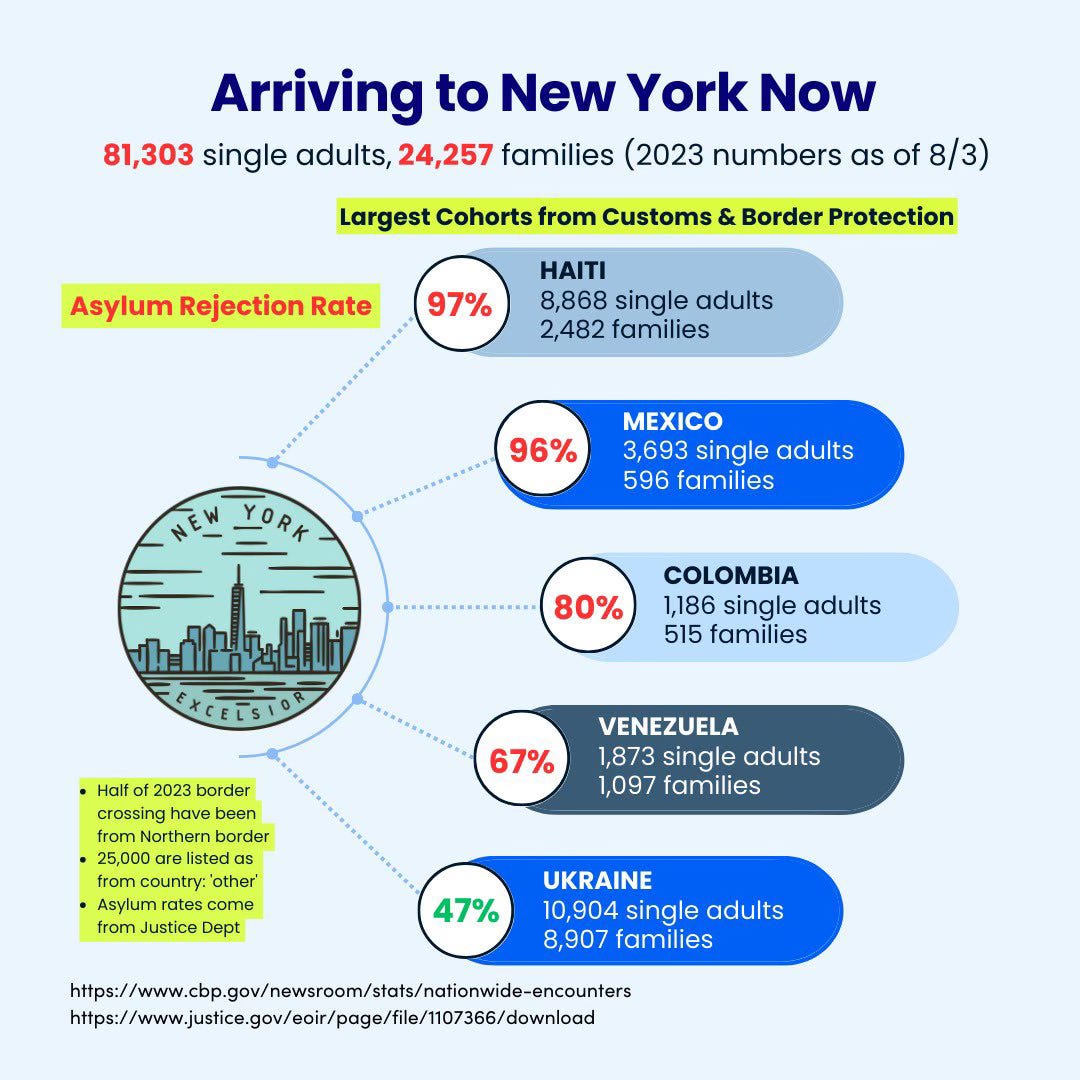

The most interesting numbers to me are the total arrivals to New York City, which FNY claims is about 105,000 in 2023 alone. This isn’t an implausible number by any means, but it conflicts with what NYC city officials have said (just this month to PBS) was 100,000 since spring of 2022. Those numbers are inconsistent by an order of magnitude that I can’t square. As I mentioned above, maybe this is what FNY meant when it expressed uncertainty about CBP’s numbers; but if it is, then FNY has a responsibility to sort that out before it publishes these numbers.

Relatedly, the numbers on how many adults and families from each nationality appear to be subdivisions of the total 105,000. Any inconsistencies in the total will trickle down into the nationalities, too, so I’m skeptical about how accurate these are. In addition to accuracy, there are two additional issues I take with how these data are used. The first concerns the reference to CBP data in the footnote in the bottom left corner. It’s entirely unclear which parts of the misinfographic are derived from CBP’s nationwide encounters data and which parts are from the data that FNY obtained directly from CBP itself.

For example, one of the bullet points claims that “Half of 2023 border crossings have been from the northern border.” If we can assume that they are using CBP’s nationwide encounters data, this is laughably wrong. Using CBP’s tool that FNY cites, the number of encounters along the southwest border is higher by a factor of about 10x compared to the northern border (see the difference in the y-axis scale in the two graphs below). And besides, these are encounters, not crossers. It’s not clear at all where the data on “crossers” is coming from or on what basis FNY is claiming that half of border crossers have been from the Northern border. Conclusion: this is just factually unsubstantiated.

The second concern I have about the CBP data is the strange design decision to put those nationality numbers next to the asylum grant rate for each of those nationalities. This is unusual and misleading since it could be interpreted to suggest that the asylum denial rate is derived somehow from the numbers to the right of it (which it is not). I believe the more negative implication (and probably the intention) is the reverse: that (for example) 97% of these recently-arrived Haitians are never going to get asylum. The concerning extension of this implicit visual argument is that, therefore, most of these Haitian migrants shouldn’t be here in the first place—and the text of the tweet above certainly guides the reader toward this interpretation of the misinfographic.

Let’s finally talk about one of the most confusing points of FNY’s misinfographic: the “asylum rejection rates.” Our first point of order (as always) is terminology. Like “qualify”, the term “rejection” is confusing and nonstandard. In immigration law, like most areas of law, there is a difference between having an application rejected and having an application denied. A rejection typically means that the application did not meet the minimum qualifications, was filed late, or failed to meet some threshold. If I filled out an asylum application and walked into the Baltimore immigration court today, the application would be rejected because I’m not eligible, because the court doesn’t have jurisdiction, and so on. That’s quite different than filing an asylum application and having it denied on its merits. I will generously assume that FNY simply doesn’t know the difference and that they mean “asylum denial rates”—but you can see the confusion.

Where does FNY get asylum denial rates? They are using EOIR’s table of asylum outcomes online here, but in a strange way. I have to be honest, this is where FNY starts to lose me but bear with me.

An important caveat here: EOIR’s table is itself a bit of a mess. Matthew Hoppick hosted a nice thread on Twitter when this spreadsheet came out about the strange math at work here. I’m not suggesting that EOIR doesn’t have some internal reason for the weirdness here, but it’s not all that legible. Specifically, the EOIR’s use of the “other” category here is expansive to the point of confusion. For example, if an asylum applicant is granted some form of relief other than asylum, it will be recorded as “other” rather than “granted”—even if the result is that they are allowed to stay in the country. While that’s not wrong wrong, it introduces some confusion about what’s really happening with these cases.

How does FNY use EOIR’s data? This is where it gets weird. FNY’s misinfographic says that 97% of Haitians are denied asylum, along with 96% of Mexicans, 80% of Colombians, and 67% of Venezuelans. Ukrainians, in green, are only denied 47% of the time; FNY has apparently decided that if you are denied less than 50% of the time, that nationality is … okay(?).

I really struggled to make this math work. EOIR’s data says that 5% of Haitians were granted, 13% were denied, and the rest were “other”. I’ve done all the permutations I can, and I can’t get to a 97% denial rate. TRAC’s data show a 66.3% denial rate for Haitians nationwide in FY 2023 so far. That number is calculated based on asylum applicants with completed cases, and if you go to TRAC’s website, you can see which of the ~34% of grants were for asylum directly versus some other form of relief. Regardless, that’s pretty far off from what FNY is claiming.

I can sort of make sense of FNY’s math on the Mexican denial rate of 96%. EOIR’s spreadsheet says that only 4% of Mexican cases were granted, and 100-4=96. The problem is, the EOIR’s own denial rate (if we’re going to use their data) also says that Mexicans have only a 16% denial rate—so why not use that number? (Probably because it doesn’t tell the story that FNY wants to tell.) Last one: FNY’s number of 80% for Colombians works out using the same math as previously: 100 minus the 20% grant rate for Colombians gives FNY an 80% denial rate. But again, this is not even superficially correct, as EOIR already calculates a 40% denial rate for Colombians—half of what FNY claims.

Through trial and error, we can reverse engineer the funny math that FNY is coming up with. This is indefensible within the EOIR’s own data because they already provide a denial rate as part of their own methodology, making it clear that you cannot subtract the grant rate from 100% to get an accurate denial rate. Further, this data on grant rate and denial rate is already produced by TRAC using a consistent and reliable calculation that is widely used—but which conflicts with FNY’s absurdly high denial rates. In short, there are so many ways that FNY could have represented these data in consistent and defensible ways, but instead, they chose to represent these numbers the one way that would be demonstrably misleading. Besides, they didn’t even do it wrong consistently. They screwed up the numbers on Haitian asylum seekers and somehow used 100% - 5% to get 97%, inflating the denial rate of Haitians and using the design of the graphic to emphasize Haitian’s purported illegitimacy in the system.

That’s about all I can say about the factually misleading design and data on FNY’s misinfographic. I was going to demonstrate a more appropriate way to represent these numbers in a way that was accurate regardless of political perspective but this is already too long. In the final section, I want to point out some more general observations and take-aways.

4. Misinformation, Disinformation, or Just Sloppy?

I want to draw this article to a close with a few sober observations about asylum outcomes and about dis- and misinformation more generally.

First, it is true that asylum outcomes vary widely by nationality and by immigration court, often in ways that have more to do with randomness and policy bias with the quality of the underlying asylum claim. One does not need to fabricate numbers or do funny math to show that. It raises serious concerns to see an organization claim to be interested in facts and honest debate, but then post artificially inflated asylum denial numbers that do not tell an honest or complete story about how asylum works. It’s also undebatable that a lot of people who are eligible under the law to seek asylum—including those migrants who are arriving in New York City now—do not end up getting asylum. That certainly raises ethical and policy questions. But to repeat myself: one can simply raise those questions and have that debate without injecting confusing and inaccurate infographics into public discourse.

Second, FNY’s misinfographic (or disinfographic?) provides a constructive example of how powerful yet misleading visual media can be, particularly when they contain such high misinformation density. Unpacking this graphic has taken far too long, and it is just one of many similar infographics out there. It is much easier to produce garbage than to clean up garbage, particularly in the immigration space. We really must do better. FNY should do better. And not just FNY, reporters also need to learn from their mistakes, too. I’ve seen two other examples of misleading graphics in the past few weeks by news outlets that should never have made it to print. I realize that the pressure to constantly produce content means that we get in a rush and get sloppy, but we really must insist on quality over quantity and facts over slanted data. Enough with the sloppy data graphics!

Finally, I want to address the question of intentionality. I do not know who staffs or funds Families for New York (I’m sure someone will tell me now) nor whether this misinfographic is intentionally or unintentionally misleading. But to be clear: it is misleading. Period. It could be politically motivated, in which case I would encourage everyone, regardless of politics, to be more mindful of how their own biases might affect their analysis. But even if it is not politically motivated, I would still encourage everyone to also be mindful of what they’re qualified to speak about as an organization or as a professional. I don’t give car advice because I don’t understand cars. (I truly do not.) Likewise, whoever made this misinfographic at (or for) FNY truly does not understand the immigration system and should not purport to inform the public in this way. Know your limitations.

What about you: have you seen recent examples of misinformation or disinformation about immigration? If so, please share examples below.

I’m glossing over an important factor regarding what a reasonable person should have known to be questionable or false. The “Facebook uncle” trope is generally used as a stand-in for someone who is loud but not particularly well-informed. I’m thinking of my favorite SNL skits like Drunk Uncle or Second Hand News with Anthony Crispino, both characters that derive their humor from being obviously and irrefutably wrong about even basic facts. If, however, your uncle is reasonably well-educated to the point where he really ought to have questioned the underlying claims of, say, the Big Lie, this likely crosses into participatory disinformation rather than simply misinformation.

Do I need to say out loud that this is tongue-in-cheek? Yes. Yes, I do. Or someone will get confused.

Families for New York is a group that I know nothing about and refuse to do any background research on for this article in case it might bias me one way or another about how to interpret their post. The tweet is here:

https://twitter.com/familiesfornyc/status/1695100389840875637

Enjoyable piece to read! We all need to know the limits of our knowledge too. These issues are so complex.

Thanks for this unpackaging of mis (dis) information, Austin. SO much of it going around, IMO intentionally scaring people about "the other". We are all immigrants. ✌️