New Data Sheds Light on Deportation Process

TRAC released a new online data tool last week that allows the public to see detailed information about new deportation cases1 for the first time ever.

Deportation continues to be a controversial and politicized topic. This new data tool promises to provide greater transparency to everyone, regardless of users’ political perspectives, since the data in the tool are obtained directly from the federal government using the Freedom of Information Act rather than collected by individual researchers.

TRAC’s “New Deportation Proceedings” tool shows information about the age, language, nationality, and gender of immigrants facing deportation, as well as information about the case itself, including where and when the case was filed.

Immigration 101: When the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) wants to deport an immigrant in the United States, the agency issues what is called a “Notice to Appear” (NTA). The NTA document begins the deportation process in the US immigration court system. At the end of this process, an immigration judge may order the non-citizen to be deported (i.e. leave the country, either forcibly or on their own), or the person may be granted asylum or some other type of what we call “relief” that allows them to stay in the United States on a temporary or permanent basis. NTAs are a powerful part of the US immigration enforcement system.

Most importantly, this new tool provides information about the most serious charges that are listed on NTAs issued by DHS. This means that we can now see how many NTAs include allegations of terrorism, serious criminal charges, or no additional charges beyond unlawful entry or unlawful presence.

As a result, we can start to quantify what academic researchers have been calling “crimmigration”—or the overlap between the criminal justice system and the immigration enforcement system.2 This is only a very small sliver of the kinds of data that are needed from federal, state, and local agencies to fully capture crimmigration—but it’s a start.

For more information about crimmigration, I encourage you to check out César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández’s Crimmigration blog, Crimmigration manual (now in its second edition), and his Twitter page here:

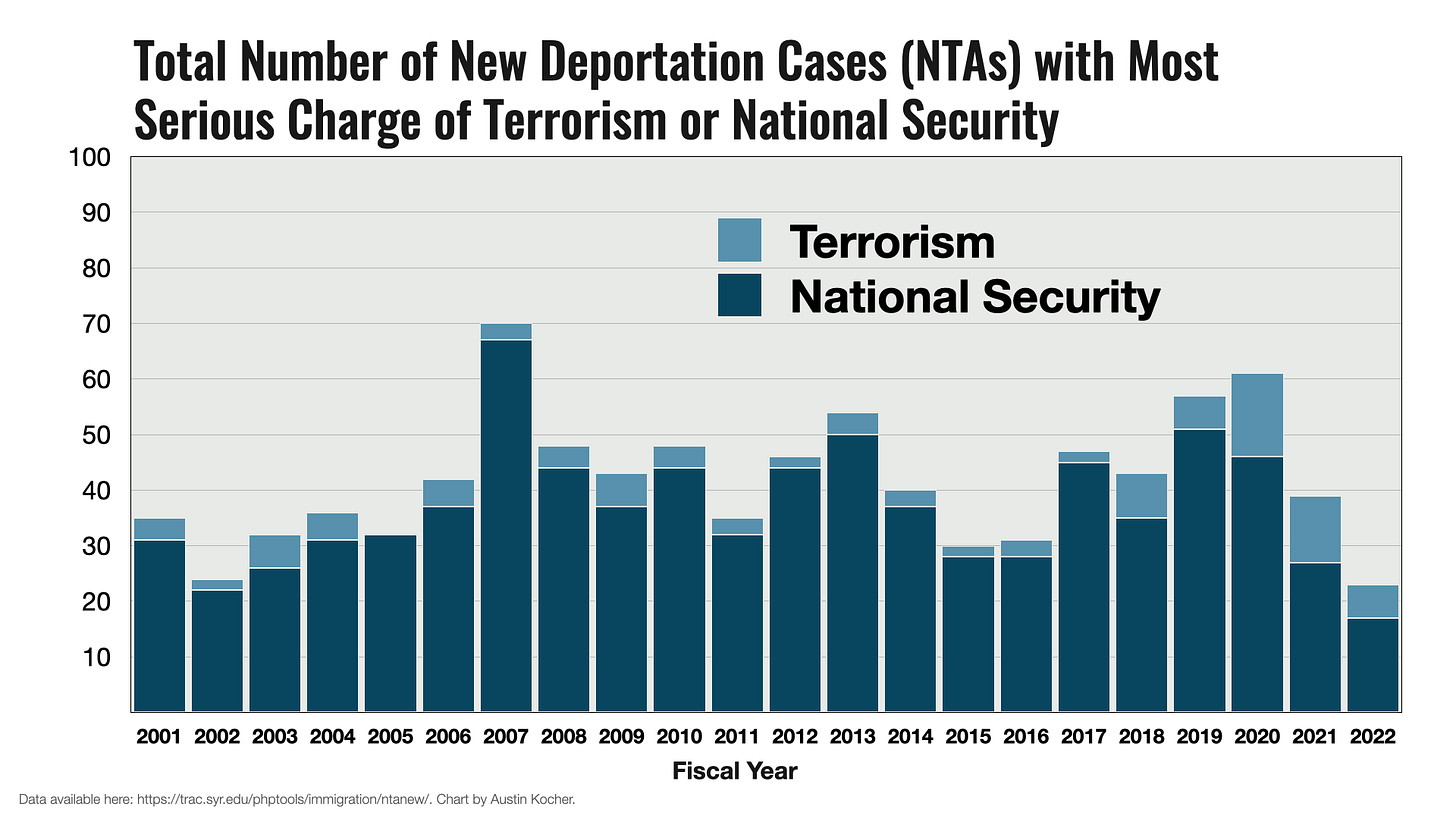

Using this new deportation case tool, I examined how many new deportation cases each year show charges for (1) terrorism and national security charges, and (2) aggravated felonies and other criminal charges. I created the two charts below to visualize these findings.

In general, terrorism and national security charges remain relatively consistent across time, but never more than 70 in a given year.

More remarkably, the total number of charges on NTAs for aggravated felonies and other criminal charges has declined significantly since 2010. Given how much scholarship has been published about this in the past, I would have expected these numbers to be higher. There is still much work to be done to fully validate and flesh out these trends, so consider these remarks very preliminary.

Please note: this does not mean that immigrants are not charged with other crimes. An NTA does not reflect the entire history of interactions that an individual has had with the criminal justice system. Indeed, so long as a person is in the United States unlawfully, no additional criminal charge is needed to begin the deportation process. There are also significant differences between what counts as a criminal conviction for the purposes of immigration law and what took place in a state or local jurisdiction.

Without belaboring the point, what I’m trying to say is: this process is complicated, so don’t over-interpret this data. But do head over to TRAC’s website and check out this new tool. Let me know if you find anything interesting that you think we should look into or post observations in the comments below.

THANK YOU FOR READING! 🙏🏼

If you found this information useful, help more people see it by clicking the ☼LIKE☼ ☼SHARE☼ button below. If you want to get this newsletter in your inbox, please subscribe.

↓

I use the term “deportation” here for its general legibility, but note that following a change in the law in 1996, the vast majority of these cases are now called “removal” cases.

You may find this article by Raul Reyes on NBC.com helpful: “How immigration policy became 'crimmigration' — and the racial politics behind it.” https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/immigration-policy-became-crimmigration-racial-politics-rcna1818