The Migrant Disappearance Protocols: Trump Sends Immigrants to "Legal Black Hole" at Guantánamo Bay

Guantánamo Bay isn’t where people go when they break the law; Guantánamo Bay is where presidents go when they want to break the law.

In an unprecedented move, the Trump administration is now transferring immigrants from detention centers inside the United States to the migrant detention center in Guantánamo Bay—and the administration appears set to expand this practice to thousands of migrants. This post will get you up to speed everything you need to know.

Let me start with an update on recent developments surrounding the politics of immigration data, then move on to discuss the Trump administration’s alarming transfer of detained immigrants to the military base at Guantánamo Bay. Believe it or not, the two things are closely linked.

The past few posts have focused on problems with immigration data that ICE was releasing to the public through its account on X (formerly known as Twitter). As I discussed previously, ICE was posting numbers of “arrests made” and “detainers sent” on a daily basis. I raised concerns about the validity of these data, and questioned whether the agency would even continue to publish these daily data points.

My intuitions were correct. ICE did give up their brief practice of posting these data points, and they did so just as the data on arrests and detainers began to decline, as they did after merely three days of otherwise fairly high numbers. No such data has been posted for the first thirteen days of February.

This confirms two of my core arguments. First, any sensationalized “surge” in immigration enforcement is unlikely to be sustainable because of the resources required for that kind of policing. Second, ICE’s use of data was clearly intended to further sensationalize the enforcement surge, albeit under the guise of objectivity and transparency (although it was neither).

Instead of posting data, ICE has gone all in on posting memes about allegedly serious criminals that they have arrested. The agency has not provided any underlying data or evidence to substantiate these claims, and we are not obliged under any administration to accept claims about criminal histories without evidence—especially when that administration has shown a contempt for the truth. As a reminder, deportation is not a criminal process, so even if criminal history plays a role in making someone deportable, the deportation itself is not technically considered a punishment for those crimes.

I previously laid out the evidence for why I consider the meme-ification of criminal immigrants a misleading practice as a question of administrative data. But now I want to turn the larger political problem exacerbated by (mis)representations of immigrants as criminals, namely the ways in which (alleged) criminality is used to build support for controversial policies and practices that are first applied to socially stigmatized groups with the goal of hiding the fact that they are going after people who don’t have criminal histories and expanding those policies and practices to a broader scope of the population.

And that brings us to Guantánamo Bay.

This newsletter is only possible because of your support. If you believe in keeping this work un-paywalled and freely open to the public, consider becoming a paid subscriber. You can read more about the mission and focus of this newsletter and learn why, after three years, I finally decided to offer a paid option.

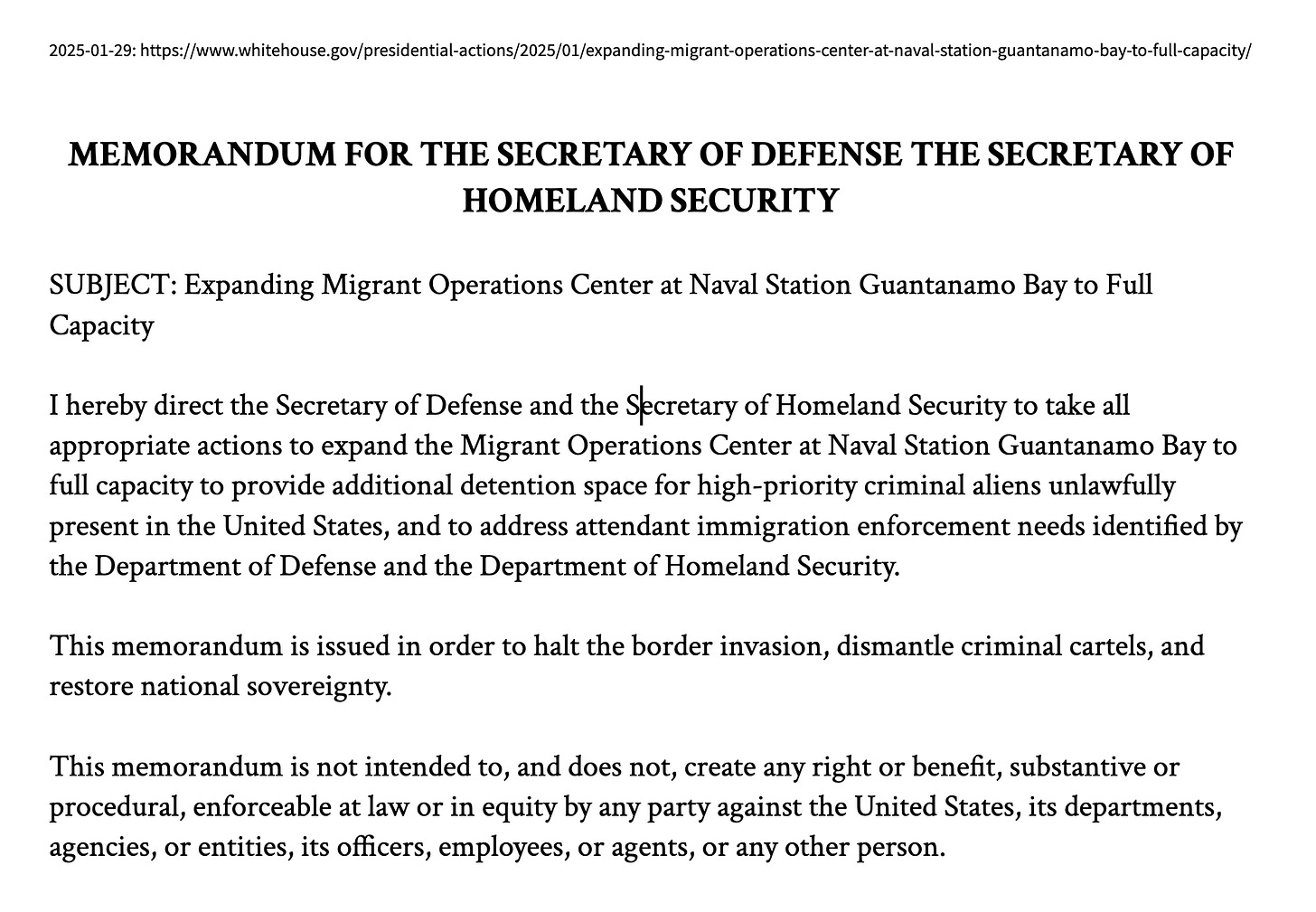

On January 29, Trump issued an executive order that instructed the Department of Homeland Security and the Secretary of Defense to expand the Migrant Operations Center at Guantánamo Bay Naval Station. The memorandum is very short.

To justify these extraordinary measures, the memo says that use of detention is reserved for “high-priority criminal aliens”. You, dear reader, will recognize that this is nothing more than a discursive strategy that the Trump administration has been using to build support for controversial detention practices. This is why I have been so persistent in confronting the myth of immigrant criminality: we know from the annals of history that authoritarian rulers predictably use the guise of criminal enforcement to build popular support for policies that ultimately expand to dangerous scales.

The other day, I wrote about the longer history of South African Apartheid as important background for Trump’s EO about treating Afrikaners as refugees. Guantánamo Bay needs an introduction, as well.

Most people are aware of this first part of Guantánamo Bay’s recent history. The Bush administration (and every administration since) has used Guantánamo Bay as a “legal black hole” to hold (alleged) enemy combatants captured during the War on Terror. I say “alleged” because while some of Guantánamo Bay’s detainees were engaged in violence, many detainees were little more than people at the wrong place at the wrong time—and this is according to Bush administration officials themselves. Nevertheless, these detainees sat for years in extra-legal confinement. Many of them were tortured. And only a handful were ever charged with a crime.

What fewer people know is that “Gitmo”, as it is sometimes called, is a relic of a period of American colonialism punctuated by the Spanish-American War in 1898, which resulted in the US’s military acquisition of Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba, the Philippines. Around this same time, the US overthrew Hawaii and supported an independence movement in the northern part of Colombia that we now know as Panama. It’s a part of forgotten history that Daniel Immerwahr describes in fascinating detail in How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States. (A reasonable person might wonder if talk of reclaiming the Panama Canal and taking over Greenland are indications we find ourselves in a similar era of American territorial expansionism today.)

I mention the Spanish-American War because it was a war that began geographically at the opposite end of Cuba from Guantánamo Bay and narratively on the pages of newspapers run by wealthy businessmen who held, at best, flirtatious relationships with the truth. (Sound familiar?) The triggering event for the war was the explosion of the USS Maine, a Navy ship docked in the Havana Harbor. Although no evidence existed that Spain had caused the explosion (experts largely agree that the explosion was a result of the coal furnace on the ship itself), this did not stop newspaper moguls William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer from running headlines just two days later (long before the military even produced its own politically-motivated report) that pointed the finger entirely at Spain and forced President McKinley somewhat reluctantly into the war. It was the 1898 equivalent of tweeting your way into a war.

The detention centers at Guantanamo Bay might not exist at all were it not for unverified claims and sensationalized headlines spread by the media to sell newspapers. Whatever legitimate differences there are between newspapers in 1898 and social media in 2025, one thing is consistent: misinformation is profitable for some unscrupulous short-sighted elites, but ultimately undermines our collective good judgement.

Like Roosevelt Roads Naval Station in Puerto Rico, where I was stationed for three of my four years of service in the U.S. Navy, Guantánamo Bay spent most of the 20th century as a fairly quiet base whose strategic value became inevitably tied to US’s anti-communism deterrence policy in Latin America during the Cold War.

But this changed dramatically in the early 1990s.

After the passage of the Refugee Act in 1980, migrants in the Caribbean, especially Haitians and Cubans, were among the first to attempt to avail themselves of humanitarian protections by attempting to make landfall on US soil to claim asylum. It might be hard to imagine today, but it took years before the US-Mexico border became the focus of asylum-seekers, dominated as it was for decades primarily as a pathways for young men recruited into the US labor market.

In 1991, when Haitians sought asylum in the US due to the military dictatorship that replaced Jean-Baptiste Aristides, the US Coast Guard began interdicting these maritime refugees and holding them at Guantanamo Bay. In 1994, the thousands of Cubans and Haitians were both held in Guantanamo Bay. However, and see if this sounds familiar, Haitians were described as “economic migrants” and therefore not eligible for asylum, while Cubans were viewed as fleeing legitimate persecution and given humanitarian pathways into the US.

Here’s another pebble thrown into the pond of history whose ripples are still felt today During this period of interdiction in the 1980s and early 1990s, the US Coast Guard were instructed (first by Reagan) to give Haitian refugees who were encountered in the open waters nothing more than a cursory questioning about their reasons for migrating to determine if any of them could be considered candidates for asylum. Unsurprisingly, almost none of these individuals held at sea by a quasi-military force without access to legal counsel were found to be eligible for asylum. This practice laid the foundations for what we now call the credible fear interview, added into law by IIRIRA in 1996—a provision that adds an extra legal hurdle to asylum seekers and is not part of the original refugee convention.

This period also gave us the Migrant Operations Center at Guantanamo Bay.

As the Global Detention Project (learn more about them here) describes, the Guantánamo Migrant Operations Center (GMOC) opened in 1991 for reasons of expediency, but has lived on to have an impact on global migration policies that punches above its weight class.

Here’s what the Global Detention Project says:

The Guantánamo Migrant Operations Center (GMOC) is an U.S. offshore immigration detention site located at the U.S. naval base in Guantanamo Bay in eastern Cuba. Initially opened in 1991 by U.S. President George H.W. Bush to house Haitian migrants interdicted at sea, the site became a focal point of U.S. efforts to block Caribbean migration and also served as inspiration for Australia's notorious Pacific Solution offshore detention regime. Previously managed by the controversial private prison firm the Geo Group, as of 2024 the GMOC was operated in collaboration with the International Organization for Migration and other contractors.

The detention center has been used more or less continuously since the 1990s, but to my knowledge not in any great numbers. The Global Detention Project shows that the facility has a capacity of 130, but that was verified in 2009 and probably does not include any expansion in capacity that the Trump administration has begun.

In the middle of political instability that hit Haiti in recent years, President Biden also considered sending interdicted Haitian migrants to Guantánamo Bay, a possible move that prompted widespread criticism from immigrant rights groups and led to calls for the closure of GMOC altogether. Despite these considerations, the Biden administration came to a close without using the GMOC to house substantial numbers of interdicted migrants.

All that changed with Trump’s Guantánamo Bay executive order.

Trump’s Guantánamo Bay EO is built upon a long history, rooted in both misinformation and US expansionism, of the US government using the base as an exceptional legal site where dehumanizing treatment is justified by misrepresenting people held there as criminals and terrorists. Trump’s EO would not be possible without this history, so it’s important that we understand it.

At the same time, Trump’s EO takes a huge and very dangerous leap forward.

Until now, people were held at Guantánamo Bay precisely so that they could not reach US soil and thereby access the various legal protections afforded to people in criminal and civil proceedings. Haitians were (mostly) interdicted in the open waters, not on US soil. Detainees captured in the War in Terror were captured abroad and brought there.

Trump’s use of Guantánamo Bay is unprecedented in that they are moving immigrants in the United States out of the country to the base.

This means that family members do not know where these people are and cannot contact them. More importantly for their legal case, it means that their attorneys face additional barriers to accessing their clients much like the attorneys for war on terror detainees at Camp Delta. Finally, it is not clear at this time whether the authority of the US immigration courts or federal criminal and civil courts reaches into the GMOC. Likely not. Detaining immigrants at Guantánamo Bay means not only preventing migrants from outside of the United States from reaching the US legal system, it now means that migrants inside the US already are being plucked out of the jurisdiction of the US and raising wholly novel questions about their rights and their treatment.

Satellite images already show construction at the detention center to prepare for an influx of detainees. Great work by the OSINT (open source intelligence) community.

The first flight to Guantánamo Bay arrived from El Paso, Texas, on February 4 with 10 migrants all purportedly serious criminals. At the time of this writing, New York Times reporters claim that there are at least “several dozen” and that many of these detainees are being held not by regular GEO Group staff but by military guards. (FYI: Follow Thomas Cartwright with Witness at the Border if you want to learn more about how he tracks and publishes detailed information about ICE’s deportation flights.)

As I mentioned above, Trump’s Guantánamo Bay EO claims to focus on “high-priority criminal aliens”, specifically Venezuelans who are in the now popularized gang Tren de Aguas. If you are a regular reader of this newsletter, it will not surprise you to learn that the facts are not bearing this out well. Like previous reports of ICE’s overblown claims of going after “the worst of the worst”, reports are already surfacing of many migrants who are not serious criminals, if they even have criminal convictions at all.

Camilo Montoya-Galvez (excellent immigration reporter to follow) reports that government records show some detainees classified as “high-priority” but also shows many others who are classified as “low-priority” under the DHS’s own classification scheme. As Camilo points out, this typically means that the individuals may be in the country unlawfully but do not have any other extenuating criminal histories.

Julie Turkewitz and Hamed Aleaziz also found that one of the Venezuelan detainees, Luis Alberto Castillo, who was flown to Guantánamo Bay was not a criminal. The government asserted he had a Michael Jordan tattoo that indicated gang affiliation, then backed down from those assertions, then claimed that they had new evidence of gang affiliation—although the government refused to disclose this new evidence.

Already Trump’s EO’s claim to focus on “high-priority criminal aliens” is proven factually unverified if not wholly untrue—and we’re barely 10 days into this.

The government appears to be using the same old broken tactics that they have for years. The Trump administration is purportedly assessing gang affiliation based on tattoos. (See Beth Caldwell’s excellent article here for a legal analysis of the problems with this tactic.) They are attempting to use secret evidence to justify their assessments—which is, of course, inherently impossible to challenge when the person is held in this extra-legal facility outside of the US.

The ACLU recently filed a lawsuit against DHS on behalf of detained clients provides timely insights into what's going on, including the government’s obfuscation over how it is deciding which immigrants to transfer there and why. Like stories in the press, the lawsuit also repeats the problem with ICE making problematic assessments of “gang affiliation” based on tattoos. That lawsuit, Luis Eduardo Perez Parra et al v. Dora Castro et al, and a subsequent lawsuit files just yesterday, Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center Et. Al v. Kristi Noem, Department of Homeland Security, et al both challenge the government’s use of Guantánamo Bay. The real question now is whether the Trump administration will even follow judges’ decisions, leading us closer to a constitutional crisis.

The government is also making it increasingly impossible to even find who is located in Guantánamo Bay. As some of you know, ICE maintains an ICE Detainee Locator, an online portal where family members and attorneys can enter key biographical details about a detained person to see where they are being held. As Pablo Manríquez discovered, ICE is listing people detained in Guantánamo Bay as being detained in Miami.

Pablo also reminded us earlier today that the government has not provided as single credible report of criminal history of anyone held at Guantánamo Bay. Just as I’ve been saying for days about ICE’s enforcement data, we must be absolutely unpersuaded by baseless claims that are unsubstantiated by evidence. (By the way, Pablo runs a great Substack over at Migrant Insider.)

In sum, ICE’s recent practice of (mis)representing its enforcement surge as focused on high-priority criminals has dovetailed with its campaign to legitimize the use Guantánamo Bay as a holding site for immigrants arrested on US soil.

I want to end with one final point. Although you might think that non-citizens, especially non-citizens who have criminal records, don’t deserve our sympathy or any legal protections, the truth is, this isn’t just about them. It’s about all of us. This type of state-sponsored lawlessness is a laboratory in what the administration can get away with. If we ignore this because it “doesn’t apply to me,” we are only helping to pave the way for the next abuse of executive power.

Let’s remember that Guantánamo Bay isn’t where people go when they break the law; Guantánamo Bay is where presidents go when they want to break the law.

What do you think?

Let me know your reaction to this news about the Trump administration detaining migrants in Guantánamo Bay by taking this poll and leaving a comment below.

Consider Supporting Public Scholarship

Thank you for reading. Please subscribe to receive this newsletter in your inbox and share it online or with friends and colleagues. If you believe in this work, consider supporting it through a paid subscription. Learn more about the mission and the person behind this newsletter.

"...It is not clear at this time whether the authority of the US immigration courts or federal criminal and civil courts reaches into the GMOC. Likely not. Detaining immigrants at Guantánamo Bay means not only preventing migrants from outside of the United States from reaching the US legal system, it now means that migrants inside the US already are being plucked out of the jurisdiction of the US and raising wholly novel questions about their rights and their treatment. "

This statement gives me nightmares. What will become of these people without rights? Will they be able to plead for asylum from Gitmo? Will they be forced or sold into slavery? Tortured? And you're right--this horrific behavior by the US gov't can apply to both citizens as well as non-citizens. Just think of this as an opening to all that is coming for all of us in the near future if we don't stop it now. *shudder*

What is the motivation for using Guantánamo Bay? We've already seen examples of immigrants without criminal records being sent there. Is it really to up the ante against the cartel or other organized crime, or might it simply be, given Guantánamo Bay's checkered past, a means of striking fear in the hearts of undocumented immigrants.