Immigrant detention has been controversial from the days of Ellis and Angel Islands in the late 1800s through the emergence of a for-profit detention system in the 1980s and up until today. Although immigration restrictionists and many DHS officials view immigrant detention as necessary to deter immigration to the United States and force immigrants to show up for court hearings, many scholarly historical analyses illustrate the more troubling history of immigrant detention not as a simple policy solution, but as the product of prejudice, profiteering, and a punitive approach to what is, in fact, a civil matter.

“Despite the common refrain that immigration law is "broken," immigration imprisonment is a sign that the United States immigration policy is working exactly as designed. The system hasn't malfunctioned. It was intended to punish, stigmatize, and marginalize-all for political and financial gain.”

—César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, Migrating to Prison

Whatever your political views on the matter, a good way to stay current with immigrant detention policy and practice is to follow the data.

New data released yesterday by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) show that the number of immigrants in detention appears to have settled in at around 20,000 people at any given point in time. There has been relatively little change in recent weeks. And while no news is no news for the 24-hour news cycle, no news is news for researchers who are trying to make sense of how the Biden administration’s approach to immigration enforcement differs (or fails to differ) from previous administrations.

As I have emphasized in the past1, the data in this chart represents the number of people in detention on the day that the data is exported from ICE’s data systems. This means that we are looking at a picture—a static snapshot taken at the dates along the x-axis—not a video.

A video of ICE’s detention system would show that even though the total number of beds filled remains consistently around 20,000 at any point in time, many more people are passing through the system, then released and monitored on ICE’s alternatives to detention program.

The picture only captures a single frame—but it’s an important frame because it illustrates how many total detention beds that ICE needs to have on reserve under its current model.

Speaking of ICE detention capacity, Eileen Sullivan at the New York Times recently reported2 that the Biden administration is seeking a 25% reduction in the number of detention beds funded by Congress in his proposed budget, reducing it from 34,000 to 25,000. This is hardly a sign that President Biden is on the cusp of abolishing detention, but after years of increasing detention budgets, this does represent a significant move in the other direction.

In light of these new data, the Biden administration’s request for fewer detention beds appears defensible, even if advocates on the right would prefer to see immigrants detained rather than monitored on ATD.

A technical note: I am intentionally avoiding the term “low” to describe ICE’s detention numbers. While it is obvious and uncontroversial to describe ICE’s current detention numbers as lower than they were before the pandemic, I don’t think it’s accurate to say that they are objectively low. Twenty-thousand detained people is still an awful lot of people and to say that these numbers are “low” could lend legitimacy to this system. Although detention works somewhat differently elsewhere in the world and therefore statistical comparisons are not always apples to apples, the US detains far more migrants than any other country. As a geographer, I am a strong believer in situating the United States in a comparative global context rather than limiting the scope of our analysis only to ourselves.

One of the reasons that the Biden administration has been able to control detention numbers has been ICE’s use SmartLINK electronic monitoring (aka "e-carceration” technology) that allows the agency to monitor immigrants beyond the walls of detention centers. SmartLINK is part of ICE’s Alternatives to Detention program.

I feel compelled to emphasize that alternatives to detention is not, in fact, an “substitute” to detention (the agency acknowledges as much on their website), but a program for expanding immigrant surveillance.

I also want to emphasize that the question of whether or not these technologies are “better” than detention unhelpfully reproduces ICE’s intent when it appropriated the humanitarian-sounding “alternatives to detention” language from grassroots NGOs in the 1990s.3

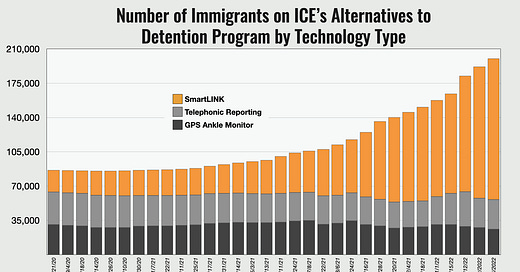

With that said, ICE’s latest data continue to show that SmartLINK is driving enormous grown in the number of people monitored on ATD technology. The agency’s use of telephonic reporting and GPS ankle monitors (not “ankle bracelet”; for Pete’s sake, stop saying “bracelet”) have remained entirely flat, while SmartLINK has grown enormously in under two years. I am laboring under the assumption that we’ll see at least half-a-million immigrants monitored on SmartLINK in the next five years, if not more.

BI, Inc. is the company behind ICE’s ATD program. BI, which I recently found using a simple Google Maps search is located in what appears to be a defense contractor park in Colorado, was acquired by Geo Group in 2011 for nearly half-of-a-billion dollars.

An article by La Prensa Latina illustrates how SmartLINK technology works in practice through the story of Danny Sanchez.

"Every Thursday at 11 am I have to send a picture of my face to immigration," Danny Sanchez, a Venezuelan attorney who has requested US asylum and who ICE is being monitored via SmartLink. "However, for others their telephone rings every little while for them to post their photo. It can be in the morning, at night or at any hour of the day, and they're always scared to be without their phone," he said.

Recent reporting by Johana Bhuiyan for The Guardian gives a behind-the-scenes look into the inner working of BI, Bhuiyan, who spoke with former BI staff members, writes:

“Many of the former employees were struck by the enormous power they wielded over people's lives, and how few protocols there were governing crucial decisions in the program.”

These concerns appear to have struck a note with some lawmakers who recently expressed concern over the ways in which SmartLINK technology is used (or could be used) as a more expansive form of surveillance. Their letter says:

"This technology has the capability of surveilling not only the subject but also bystanders – including US citizens and individuals with legal status – raising further civil rights concerns and creating a potential for unwarranted surveillance.”

See three of Bhuiyan’s articles here:

Poor tech, opaque rules, exhausted staff: inside the private company surveilling US immigrants.

A US surveillance program tracks nearly 200,000 immigrants. What happens to their data?

‘Constantly afraid’: immigrants on life under the US government’s eye.

Clearly awareness—and concern—about SmartLINK technology is growing. Stay tuned here for more upcoming discussion about alternatives to detention research. As always feel free to post comments, questions, and additional information in the interactive section below.

THANK YOU FOR READING! 🙏🏼

If you found this information useful, help more people see it by clicking the ☼LIKE☼ ☼SHARE☼ button below. If you want to get this newsletter in your inbox, please subscribe.

↓

For more on the problematic history of this language, see Immigration Cyber Prisons: Ending the Use of Electronic Ankle Shackles.

Austin, your newsletters are so incredibly informative and the first article cited made me cry! The way we treat these people like criminals! And these agencies are paid for case management but employees are not allowed to help people. They lump all the services into one. It's all profit driven. What has happened to our basic humanity? And while he was deporting like crazy, the use of these things increased during Obama's presidency... 😢😢😢