When we imagine the border only as a line on a map, we ignore the constantly changing infrastructure that creates borders as places of division and connection. Today we will look at the border from a fresh perspective by diving into the overlooked world of art and architecture at ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border. Along the way, we will discover unusual art projects hidden in plain sight.

Welcome back. My name is Austin Kocher, and I’m a professor who writes about the fascinating world of immigration. If you’re new, welcome! 🙏🏼 You can learn more about this newsletter on the “about” page—and please consider subscribing.

Globalization Transformed the Architecture of Ports of Entry Over the 20th Century

The U.S.-Mexico border runs from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. Dotted along its 2,000-mile stretch are a few dozen ports of entry and other border-crossing locations, each with its own processing capacity and architectural style.

Globalization in the 20th Century increased the flow of people, finance, and goods across borders, yet only one—people—saw corresponding restrictions. Borders became less permeable to people at the same time as they became more permeable to international finance and commodities.

In 1922, two years before the creation of the Border Patrol, drivers barely stopped while crossing back and forth between San Diego and Tijuana. But by the early 21st Century, the San Ysidro port of entry was the busiest land port in the world, processing 70,000 northbound vehicles and 20,000 pedestrians per day. The photographs below, taken exactly 100 years apart, illustrate this historical change.

Mid-Century Architecture of Ports of Entry

After World War II, a new wave of ports of entry were built with a characteristic style that can still be easily identified today. The (then) new ports of entry were constructed as white mid-century buildings with a red or white arch that almost reflects the design aesthetic of the era’s most iconic capitalist success: McDonald’s.

This design still stands today in cities like Brownsville (left) and Nogales (right), where the arches can be seen from a distance.

The New Architecture of Ports of Entry

The latest round of new and renovated ports of entry reflects a new design philosophy that reflects the post-9/11 securitization landscape. The movement of goods across the border is being made more efficient by the use of electronic technologies and ports of entry that seek to maximize flow.

The recently redesigned industrial ports at Columbus, New Mexico, and the Mariposa port at Nogales, Arizona, are more industrial and more digital. Architecture Magazine praised the new Mariposa design in 2014 as combining “security” with “serenity”.

🌎 Nogales, Arizona (Mariposa) POE on Google Maps

🌎 San Ysidro POE (Pedestrian East) on Google Maps

The Art in Architecture Program

If you visit one of these newer ports of entry, you might catch something that is not present in the older ports. Newer ports of entry (POE) include art installations.

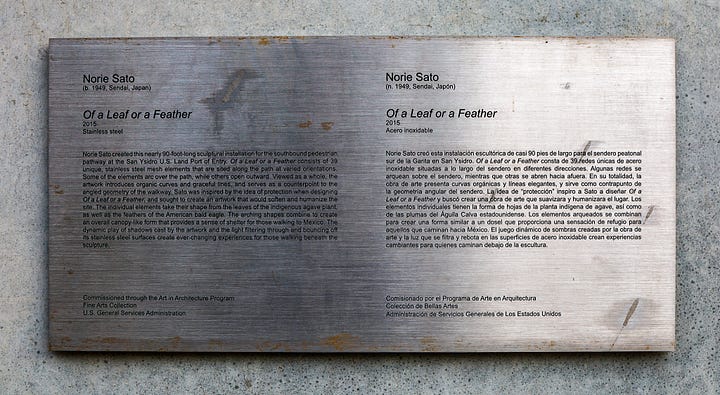

Let’s take the San Ysidro pedestrian path above. If you walk with me into the twists and turns of the metal hallway above, you will come out in a desert garden pathway that leads closer to the Mexican border. On this route, you will find an art installation titled “Of a Leaf or a Feather” by Norie Sato.

The installation is subtle, but I knew almost immediately what it was. Here’s why. Several years ago while researching immigration court hearings in Cleveland, Ohio, I passed under an enormous statue of Venus while entering the relatively new Carl B. Stokes courthouse every day. 🌎 Carl B. Stokes Courthouse on Google Maps

I ignored it at first, but as I wrote up my ethnographic field notes, I began to notice it more. I learned that the statue was made possible through a program at the Government Services Administration called the Art in Architecture program, which reserves 0.5% of the budget of every federal construction project for adding original art to public buildings.

This program, which has been operating since the 1960s, is responsible for an enormous number of artworks across the country—and also generated considerable controversy.

For instance, in the 1980s, an art installation called “The Tilted Arc” by Richard Sera in New York City was so controversial that it generated a court case and was eventually demolished.

The Art in Architecture program was later politicized by President Trump when he ordered all art under the program to fit a more nationalistic definition that favored art that was “lifelike or realistic” and not “abstract or modernist.” The order was issued in the heat of widespread attempts to remove statues of Confederate heroes and Christopher Columbus. (See my post about Charlottesville.) President Biden later overturned this order.

Art Installations at New Ports of Entry

Despite occasional controversy, the Art and Architecture program remains responsible for art surrounding new ports of entry. I already mentioned one above, but there’s more.

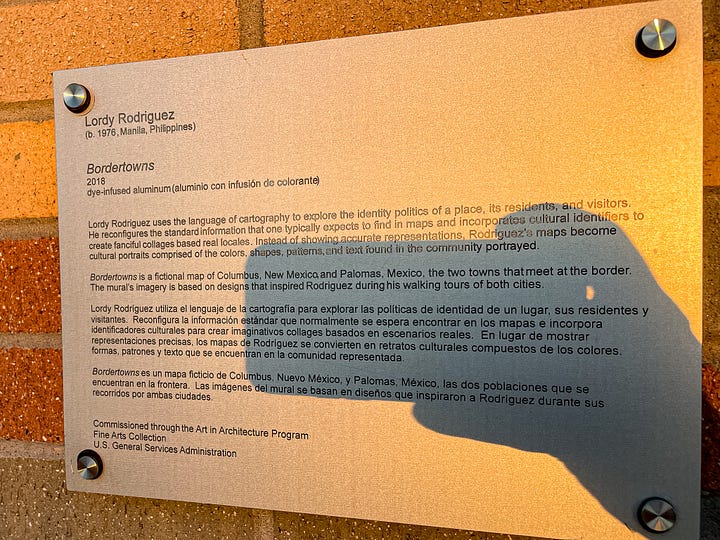

Outside the pedestrian building at the Columbus port of entry is my favorite art installation: Bordertowns by Lordy Rodriguez. The colorfully rhizomatic map connects cities south of the border with Columbus, New Mexico on the U.S. side, in a creatively topological and networked style that deconstructs the border itself.

I liked the artwork so much that I immediately found Lordy’s email and wrote her right away to ask her about it. She described the work as being ten years in the making, long before it was completed and installed in 2019 and long before the immigration policies of the Trump administration exacerbated the humanitarian crisis for migrants along the border.

In contrast to Lordy’s art, the art installation at the Mariposa POE is creepy. I visited Mariposa in late 2022 as part of a broader research project on the border.

Mariposa is primarily for industrial traffic. (Pedro De Velasco from the Kino Border Initiative told me that ports of entry like this one represent the flow of vegetables north into the U.S. and the flow of guns south into Mexico.) The port isn’t really intended for foot traffic, so to cross, one has to walk along the highway and down a gravel path before continuing on through a partly covered sidewalk that leads into Mexico.

While walking with Pedro and a team from Witness at the Border, I saw further evidence of the GSA’s Art in Architecture program. Pressed into the cement along a wall were footprints of what appear to be the foot trails of military boots or construction boots which cross with the much smaller footprints of a child.

It’s difficult to describe what makes this creepy. It gives off “footprints in the sand” vibes, but also gives the impression of a child being chased by a Border Patrol officer. The ambiguity arises from the nature of the boots themselves. Are they military boots? Are they construction boots? The undirected flow of adult footprints, when contrasted with the directional flow of the child’s footprints, lends to the chaos.

I wanted to know more, so I found the design statement. Jones Studios, Inc., the architects on the project, say that they were motivated by the border as a thing that connects rather than divides, and they describe the footprints simply as follows:

“A pattern of footprints are cast in the exposed face of the insulated concrete walls, alluding to the journey that many migrants take across the border each day.”

That wasn’t enough information to settle the question, so later, at a happy hour with reporters at the Tuscon Sentinel, I asked if others had seen this unsettling installation. Paul Ingram said he had seen it and confirmed that it was definitely weird! Follow Paul’s work online on Twitter/X and at the Tucson Sentinel by the way. He’s amazing, one of the best in the region and he often covers immigration.

Artistic Critiques of the Border

Although this post focuses on the evolution of the architecture of ports of entry and the public art installed there now, I want to highlight artistic projects that aim to critique the border.

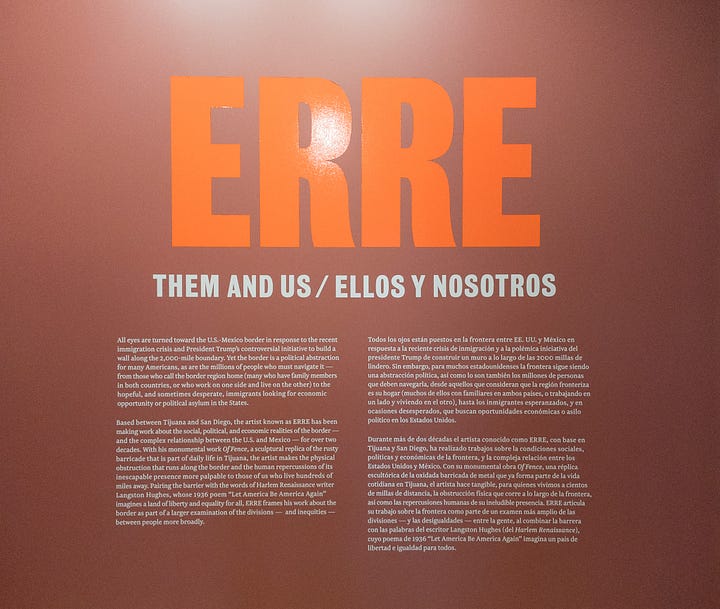

One such artist is Marcos Ramírez Erre (ERRE), whose work exhibited at MASS MoCA includes an image of a stunning two-headed trojan horse that was previously installed at the border in Southern California.

Among the most famous and recognizable artists is Rael San Fratello. His iconic teeter-totters are just one of many artistic reinterpretations of the border wall from a place of separation to a place of social interaction. I highly recommend his book Borderwall as Architecture for a visual introduction to rethinking the border.

Key Takeaways & Reader Survey

This post has been quite a survey of art architecture along the border. I hope you enjoyed going on this journey with me. Here are three key takeaways to round things out.

Ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border have evolved significantly over the 20th century, reflecting changes in globalization, security, and technology. This can be seen in the architecture of ports.

Changes in architecture have been accompanied by changes in public art. The GSA’s Art in Architecture program integrates art—often in subtle and contradictory ways—into new and remodeled ports of entry. Seek, and you will find them!

Artistic critiques of the border, such as the works by Marcos Ramírez Erre (ERRE) and Rael San Fratello, contrast with official artistic installations by seeking to explicitly critique and reimagine the social and political spaces of the border.

Please provide further feedback in the comments below about whether you found this essay interesting — or let me know if I missed something, got something wrong, or to add your own thoughts.

Further Reading

This isn’t my first post about border art and architecture. Previous posts examined border fences, border walls, and an art exhibit at the National Building Museum about the history and geography of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Support public scholarship.

Thank you for reading. If you would like to support public scholarship and receive this newsletter in your inbox, click below to subscribe for free. And if you find this information useful, consider sharing it online or with friends and colleagues.

This was interesting. The video of the teeter-totters made me remember that, after it all, I love humanity!